- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Latest News

Latest News

Paris Plus Ten: The Green Shift Gains Speed

Paris Accord

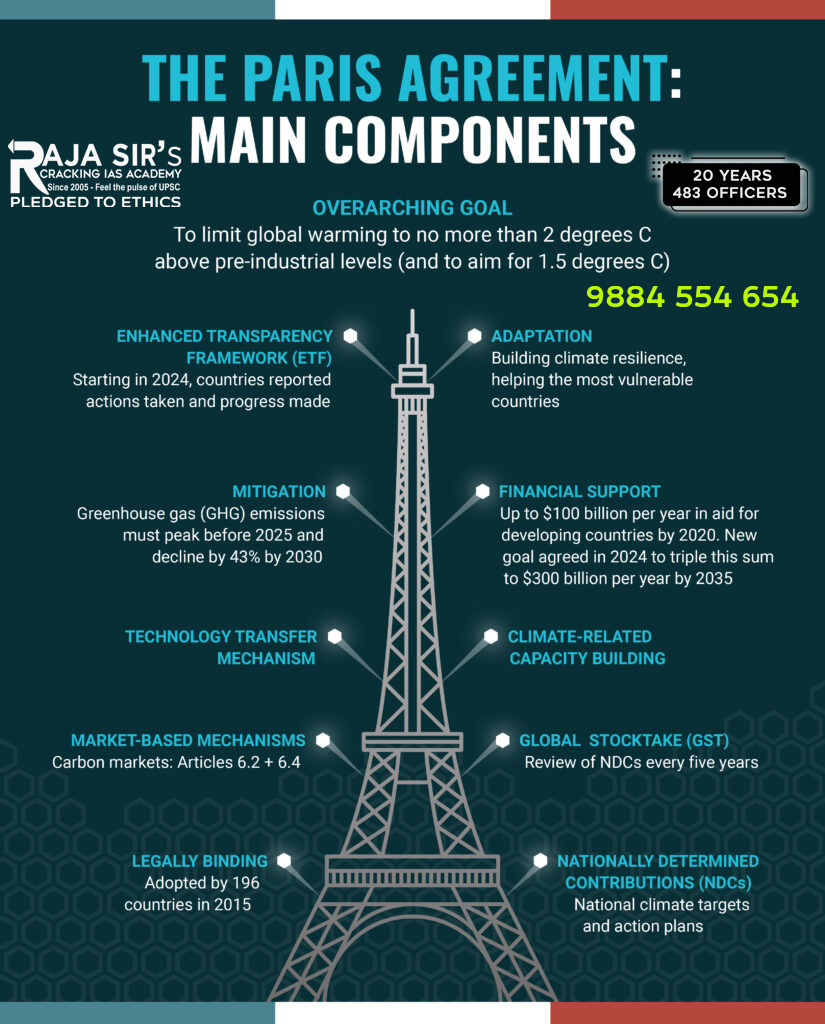

- Legal Foundation: A legally binding treaty adopted by 195 Parties at COP21 (Paris, 2015) and in force since 4 November 2016, with ratifications tracked by the UN Treaty Depositary under the UN Secretary-General.

- Core Temperature Goal: Seeks to limit global warming well below 2°C and pursue 1.5°C, as breaching this threshold risks severe droughts, heatwaves, and floods.

- Scientific Urgency: The IPCC warns that to stay below 1.5°C, emissions must peak before 2025 and decline 43% by 2030, demanding immediate action.

- Universal Participation: For the first time, all countries agreed to a common legal framework for mitigation and adaptation, balancing global ambition with national flexibility.

- Operational Cycle (NDC Framework): Works on a five-year ratchet cycle where nations submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) with progressively higher targets guided by science.

- Long-Term Strategies (LT-LEDS): Encourages nations to adopt long-term low-emission strategies linking short-term NDCs with sustainable and net-zero goals.

- Support Architecture: Provides for finance, technology, and capacity-building, with developed nations funding mitigation and developing nations receiving support for resilience.

- Transparency and Global Stocktake: Through the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF), countries report progress from 2024, feeding into a five-year Global Stocktake to assess and raise collective ambition.

Impact and Progress of the Paris Agreement

- Before the Agreement, global warming was projected to reach 4°C-5°C by century''s end. Now, it''s adjusted to 2°C-3°C due to collective actions.

- The Agreement emphasizes fairness, justice, and international solidarity, recognizing diverse national circumstances.

- Globally, the economic transition to low-carbon energy is underway, with renewable energies like wind and solar leading growth and job creation.

Technological Advancements and International Cooperation

- Electric vehicle sales now represent nearly 20% of new car sales worldwide, driven by advances in battery technology.

- The International Solar Alliance (ISA), launched by India and France, showcases international cooperation in promoting solar energy.

India''s Leadership in Climate Action

- India achieved 50% of its installed electricity capacity from non-fossil sources ahead of the 2030 target.

- The nation aims for a low-carbon pathway and net-zero emissions by 2070.

|

COP & Year |

Venue |

Key Outcomes and Achievements |

|

COP21 (2015) |

Paris, France |

Adoption of the legally binding Paris Agreement by 195 Parties; global temperature goal set to well below 2°C with efforts to limit to 1.5°C; introduction of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs); establishment of a five-year cycle to raise ambition; recognition of equity and Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR). |

|

COP22 (2016) |

Marrakech, Morocco |

Initiation of the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action linking governments, businesses, and civil society; agreement on timelines to develop the Paris Rulebook for implementation. |

|

COP23 (2017) |

Bonn, Germany (Presided by Fiji) |

Launch of the Fiji Momentum for Implementation; emphasis on adaptation and resilience for small island developing states; progress on Loss and Damage and climate finance. |

|

COP24 (2018) |

Katowice, Poland |

Adoption of the Katowice Climate Rulebook outlining operational guidelines for implementing the Paris Agreement; finalisation of rules for NDCs, transparency, and the Global Stocktake; inclusion of a just transition framework for workers. |

|

COP25 (2019) |

Madrid, Spain |

Reaffirmation of global commitment to the Paris goals; limited progress on carbon markets (Article 6); recognition of the oceans–climate nexus as a critical area of action. |

|

COP26 (2021) |

Glasgow, United Kingdom |

Adoption of the Glasgow Climate Pact; first global call to phase down unabated coal and end fossil-fuel subsidies; reaffirmation of the 1.5°C goal; announcement of India’s Net Zero by 2070 and Panchamrit strategy. |

|

COP27 (2022) |

Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt |

Establishment of the Loss and Damage Fund for vulnerable nations; recognition of just transition pathways; decision to revisit and strengthen NDCs by 2023 to align with the 1.5°C goal. |

|

COP28 (2023) |

Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

Completion of the first Global Stocktake (GST); recognition of the need to transition away from fossil fuels; operationalisation of the Loss and Damage Fund with over $700 million pledged. |

|

COP29 (2024) |

Baku, Azerbaijan |

Agreement on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) to replace the $100 billion annual finance target post-2025; focus on enhanced adaptation funding and technology transfer mechanisms. |

|

COP30 (2025) |

Belém, Brazil |

Marking 10 years of the Paris Agreement; review of first GST outcomes; reaffirmation of multilateralism; emphasis on five global priorities—emission reduction, just transition, protection of natural sinks, empowerment of non-state actors, and defense of climate science. |

Challenges to the Paris Agreement

- Warming Overshoot and Weak Implementation: Global emissions remain on a 2.7°C trajectory, exceeding the Paris 1.5°C limit, as many nations delay updating or meeting their NDCs, reflecting the absence of binding compliance mechanisms and weakening global decarbonisation efforts.

- Finance Deficit and Diluted Commitments: Developing nations require around $6 trillion annually till 2030, yet finance flows remain inadequate.

- The Baku Deal (2025) raised the long-standing $100 billion target to only $300 billion from 2035, while disputes under the NCQG over fund sources, contributors, and grant–loan balance stalled climate finance reform.

- Inequitable Burden and Erosion of Trust: The Global South—especially South Asia, Africa, and small island nations—faces the worst climate losses despite minimal emissions, while developed countries’ efforts to dilute historical responsibility and the possibility of another U.S. withdrawal deepen mistrust in multilateral mechanisms.

- Technical and Institutional Bottlenecks: Unresolved issues under Article 6 on Corresponding Adjustments and Share of Proceeds block carbon market operations; the Global Goal on Adaptation lacks measurable indicators; and weak transparency frameworks hinder accountability and effective progress assessment.

- Geo-Economic and Trade Frictions: The EU’s CBAM imposes carbon tariffs acting as non-tariff barriers for developing nations; the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has triggered a green subsidy race, prompting India’s PLI schemes.

- Also the competition for critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel has reshaped global resource geopolitics.

- Domestic Transition and Fiscal Strain (India): India faces dual challenges of ensuring a just transition in coal-dependent regions and addressing hard-to-abate sectors like steel and cement, as high costs of Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS) and Green Hydrogen, along with limited fiscal space, demand green budgeting, carbon pricing, and innovative financing such as green bonds.

- Legal, Ethical, and Information Challenges: The Vanuatu-led UNGA resolution (2024) seeking an ICJ advisory opinion links climate obligation to human rights and intergenerational justice, while widespread climate misinformation and politicisation of science erode evidence-based policymaking and global consensus.

Road ahead

- The world must accelerate collective emission reduction efforts and adopt ambitious, science-based national targets.

- There should be a just and inclusive transition, prioritising adaptation, resilience, and support for vulnerable communities through mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund, Loss and Damage Fund, and CDRI.

- Protection of natural carbon sinks, including forests, mangroves, and oceans, must become a central strategy in global climate action.

- Empowering local governments, businesses, and civil society is essential to translating climate goals into action on the ground.

- Defending climate science and strengthening institutions like the IPCC are vital to combat disinformation and ensure evidence-based policy.

- Developed nations should ensure predictable and equitable climate finance to bridge the implementation gap.

The Paris Agreement''s transformation path is deemed unstoppable due to the necessity of adaptation, irreversible industrial investments, sustainable local policies, and the resilience of multilateralism. Benoît Faraco, France’s Special Envoy for Climate Negotiations, emphasizes the continued importance of coordinated global efforts to address climate change.

General Studies

General Studies