- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

Mar 22, 2022

YEMEN'S HOUTHI REBELS HIT ARAMCO, OTHER FACILITIES IN SAUDI ARABIA

Recently, Yemen’s Houthi rebels hit Aramco, other facilities in Saudi Arabia.

Who are the Houthis, and why is there a war in Yemen?

Who are the Houthis, and why is there a war in Yemen?

What is the Par Tapi Narmada river-linking project?

What is the Par Tapi Narmada river-linking project?

About International Day of Forests

About International Day of Forests

Key Findings

Key Findings

About Namma Oor Thiurvizha

About Namma Oor Thiurvizha

Key Findings

Key Findings

About National Judicial Infrastructure Authority of India

About National Judicial Infrastructure Authority of India

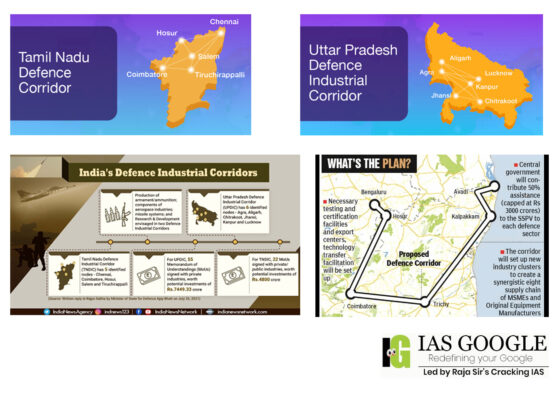

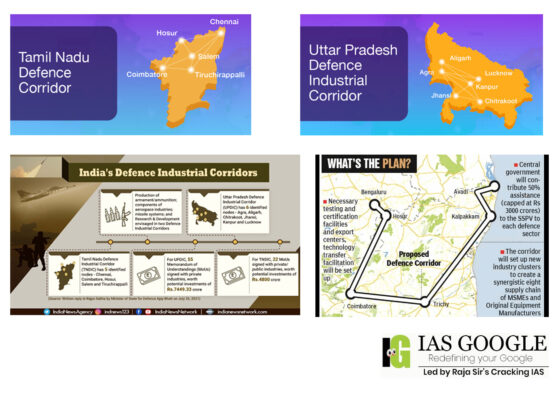

About Defence Corridor Projects

About Defence Corridor Projects

Who are the Houthis, and why is there a war in Yemen?

Who are the Houthis, and why is there a war in Yemen?

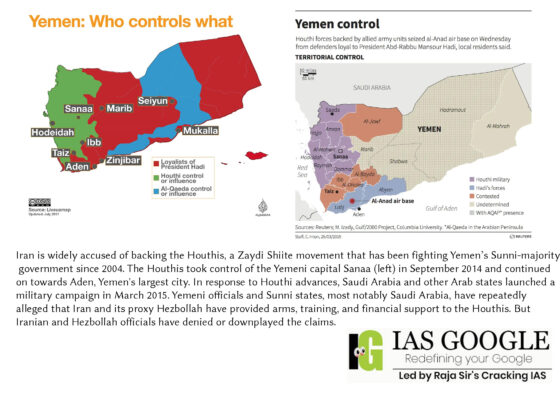

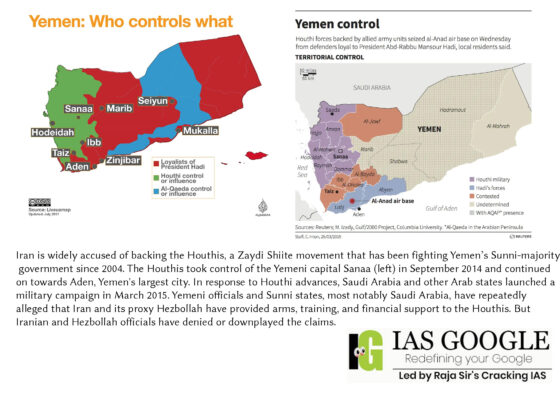

- The Houthis are a large clan belonging to the Zaidi Shia sect, with roots in Yemen’s north-western Saada province. Zaidis make up around 35 per cent of Yemen’s population.

- The Zaidis ruled over Yemen for over a thousand years until 1962, when they were overthrown and a civil war followed, which lasted until 1970. The Houthi clan began to revive the Zaidi tradition from the 1980s, resisting the increasing influence of the Salafists, who were funded by the state.

- In 2004, the Houthis began an insurgent movement against the Yemeni government, naming themselves after the political, military, and religious leader Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, who was assassinated by Yemeni security forces in September of that year. Several years of conflict between the Houthis and Yemen’s Sunni majority government followed.

- In 2012, Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had been Yemen’s president since 1990 (and before that, president of the pre-unification country of North Yemen from 1978 onward), was forced to step down in the wake of the Arab Spring protests. He was succeeded by his vice-president, Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi.

- In 2015, Saleh aligned himself with the Houthis against Hadi, and the insurgency — which at the time had the support of many ordinary Yemenis including Sunnis — captured Sana’a. The president fled to Aden and subsequently to Saudi Arabia, where he continues to spend most of his time.

- In 2017, however, Saleh broke his alliance with the Houthis, and crossed over to the side of their enemies — the Saudis, the UAE, and President Hadi. That December, Saleh was assassinated.

- What is the relationship between Houthis and other Islamists in Yemen?

- The Houthis have a tense relationship with Islah, a Sunni Islamist party with links to the Muslim Brotherhood. Islah claims the Houthis are an Iranian proxy, and blames them for sparking unrest in Yemen. The Houthis, on the other hand, have accused Islah of cooperating with al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

- After the Houthis took over Sanaa in September 2014, Islah initially took a few steps towards reconciliation. In November, top Islah and Houthi leaders met to discuss a political partnership. Islah called on the Houthis to cease attacks on Islah members and to release Islah prisoners. In December, the United Nations and Gulf Cooperation Council brokered a deal between the two groups to cease hostilities.

- But clashes between the Houthis and Islah continued. In the first four months of 2015, the Houthis kidnapped dozens of Islah party leaders and raided their offices. By April, more than 100 Islah leaders were detained by the Houthis. Tensions increased after Islah declared support for the Saudi-led airstrikes.

- The Houthis are also at odds with Sunni extremist groups. On March 20, 2015, an ISIS affiliate calling itself the Sanaa Province claimed responsibility for suicide bomb attacks on two Zaydi mosques that killed at least 135 people and injured more than 300 others. The group issued a statement that said “infidel Houthis should know that the soldiers of the Islamic State will not rest until they eradicate them.”

- AQAP denied involvement in the mosque attacks, but has frequently targeted the Houthis. In April 2015, the group claimed responsibility for three suicide attacks that killed dozens of Houthis in Abyan, al Bayda’, and Lahij. AQAP has reportedly partnered with southern tribes to fight the Houthis.

- In March 2015, soon after Hadi was forced from power, a nine-nation coalition led by Saudi Arabia, which received logistic and intelligence support from the United States, began a bombing campaign against the Houthis. The air attacks were in support of Hadi’s forces, who were seeking to take back Sana’a from Houthi control.

- At the heart of the intervention, however, lay the region’s fundamental power struggle — between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Riyadh and the west believe that the Houthis are backed militarily and financially by the regime in Tehran.

- Saudi Arabia shares an over 1,300-km border with Yemen. In the beginning, Riyadh claimed that the war would be over in just a few months. However, the coalition has made only limited progress since then, the war is stalemated, the Houthis remain in power in Sana’a, and a humanitarian catastrophe has unfolded in Yemen.

- Since 2015, the battle has constantly shifted shape, with the participants switching sides among the Saudi-backed forces known as Popular Resistance Committees, the Iran-backed groups, and various shades of Islamist militants including those linked with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State.

- What’s the latest in the conflict?

- The six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council invited the Houthis for talks on Yemen on the conflict in Riyadh from March 29.

- But earlier this week, the rebels said they would welcome talks with the coalition if the venue is a neutral country, including some Gulf states.

- It also said that the priority was lifting “arbitrary” restrictions on Yemeni ports and Sanaa airport.

- Yemen has been drawn into a civil war since 2014 when the Iran-backed Houthis ousted the government.

- The rebels took control of the country’s northern parts, including the capital, Sanaa, forcing the internationally recognized government to flee to the south.

- The Saudi-led coalition has been fighting the rebels in Yemen since 2015.

- Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil giant, said production of 5.7 million barrels a day — well over half of the nation’s overall daily output — was suspended.

- The shutting down of the facilities for more than a few days would affect the global oil supply.

- Crude prices will still rise a bit, but apparently the world economy dodged a bullet.

- The attacks not only exposed a Saudi vulnerability in the war against the Houthis, but also demonstrated how relatively cheap it has become to stage such high-profile strikes.

- The strikes illustrate how using cheap drones is adding a new layer of volatility to the Middle East. Such attacks not only damage vital economic infrastructure, but can also increase security costs, disrupt markets and spread fear.

- The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is a political and economic union of Arab states bordering the Gulf. It was established in 1981 and its 6 members are the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, Kuwait and Bahrain.

- The GCC’s prime geographical location is at the crossroads of the major Western and Eastern economies. The established and efficient air and sea connections and developed infrastructure make it a great place to establish and expand business.

- Since the discovery of oil, the GCC region has undergone a profound transformation and is now home to some of the fastest growing economies in the world.

- Today, the governments of the GCC countries undertake successful efforts to diversify their economies away from dependence on hydrocarbon industries.

- These diversified growth sectors, such as finance, logistics, aviation, communications, healthcare and tourism provide abundant business opportunities. Liberal climates towards foreign cooperation, investment and modernization result in extensive diplomatic and commercial relations with other countries.

- All current member states are monarchies, including three constitutional monarchies (Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain), two absolute monarchies (Saudi Arabia and Oman), and one federal monarchy (the United Arab Emirates). Yemen being the only country of the Arabian Peninsula not yet a member of the GCC.

- During the Arab Spring in 2011, Saudi Arabia raised a proposal to transform the GCC into a "Gulf Union" with tighter economic, political and military coordination, regarded as a move to counterbalance the Iranian influence in the region.

- The GCC Supreme Council is composed of the heads of the member states. It is the highest decision-making entity of the GCC, setting its vision and goals. Decisions on substantive issues require unanimous approval, while issues on procedural matters require a majority. Each member state has one vote. Its presidency is rotatory based on the alphabetical order of the names of the member states.

- The Ministerial Council is composed of the Foreign Ministers of all the member states. It convenes every three months. It primarily formulates policies and makes recommendations to promote cooperation and achieve coordination among the member states when implementing ongoing projects.

- Its decisions are submitted in the form of recommendations for the approval of the Supreme Council. The Ministerial Council is also responsible for preparations of meetings of the Supreme Council and its agenda. The voting procedure in the Ministerial Council is the same as in the Supreme Council.

- The Secretariat is the executive arm of the Gulf Cooperation Council. It takes decisions within its authority and implements decisions approved by the Supreme or Ministerial Council. The Secretariat also compiles studies relating to cooperation, coordination, and planning for common action.

- It prepares periodical reports regarding the work done by the GCC as a whole and regarding the implementation of its own decisions.

- On 15 December 2009, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia announced the creation of a Monetary Council to introduce a single currency for the union. The board of the council, which set a timetable and action plan for establishing a central bank and choosing a currency regime, met for the first time on 30 March 2010.

- Kuwaiti foreign minister Mohammad Sabah Al-Sabah said on 8 December 2009 that a single currency may take up to ten years to establish. The original target was in 2010. Oman and the UAE later announced their withdrawal from the proposed currency.

- In 2014, major moves were taken to ensure the launch of a single currency. Kuwait's finance minister stated that a currency should be implemented without delay. Negotiations with the UAE and Oman to expand the monetary union were renewed.

- The GCC Patent Office was approved in 1992 and established soon after in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Applications are filed and prosecuted in the Arabic language before the GCC Patent Office in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which is a separate office from the Saudi Arabian Patent Office. The GCC Patent Office grants patents valid in all GCC member states. The first GCC patent was granted in 2002. As of 2013, it employed about 30 patent examiners.

What is the Par Tapi Narmada river-linking project?

What is the Par Tapi Narmada river-linking project?

- The Par Tapi Narmada link project was envisioned under the 1980 National Perspective Plan under the former Union Ministry of Irrigation and the Central Water Commission (CWC). The project proposes to transfer river water from the surplus regions of the Western Ghats to the deficit regions of Saurashtra and Kutch.

- It proposes to link three rivers — Par, originating from Nashik in Maharashtra and flowing through Valsad, Tapi from Saputara that flows through Maharashtra and Surat in Gujarat, and Narmada originating in Madhya Pradesh and flowing through Maharashtra and Bharuch and Narmada districts in Gujarat.

- The link mainly includes the construction of seven dams (Jheri, Mohankavchali, Paikhed, Chasmandva, Chikkar, Dabdar and Kelwan), three diversion weirs (Paikhed, Chasmandva, and Chikkar dams), two tunnels (5.0 kilometers and 0.5 kilometers length), the 395-kilometre-long canal (205 kilometer in Par-Tapi portion including the length of feeder canals and 190 km in Tapi-Narmada portion), and six powerhouses.

- Of these, the Jheri dam falls in Nashik, while the remaining dams are in Valsad and Dang districts of South Gujarat.

- The excess water in the interlinked Par, Tapi and Narmada rivers flow into the sea in the monsoon would be diverted to Saurashtra and Kutch for irrigation. During the monsoon season, the water which is supplied to Saurashtra through the state government from Sardar Sarovar dam will be saved and used for other purposes. Presently the water of Sardar Sarovar is used in urban areas and for irrigation in Saurashtra.

- State has only 2% of surface water of the available water of the country where as it covers 5% population of the country.

- Quite fertile land with average rainfall varying throughout state from 35 cm. per annum to 114 cm. per annum.

- Uneven & erratic rainfall pattern in various regions of Gujarat State.

- Surface water being insufficient ground water is being exploited to a great extent to protect agriculture and to satisfy other needs.

- The quality of water is not satisfactory. High content of Floride & salinity is harmful to the health.

- 71% area of Gujarat is water deficit area.

- 29% area of South and Central Gujarat has surplus water.

- To fulfill the water requirement of 71% of water scarce area needs to divert excess water from surplus basin.

- As per International standards if per capita availability of water is less than 1700 m3/year, the region is “water stressed”, and if less than 1000 m3/year, the region is “water scarce”.

- Saurashtra, North Gujarat and Kutch region are water scarce in which per capita water availability is 540,343 and 719 m3/year respectively.

- National Water Policy (year 2002) emphasis that water should be made available to water deficit area by transfer from other areas having surplus water.

- An integrated water resources management with equitable distribution of available Water Resources.

- Providing Livelihood and employment opportunities for balanced regional economic development.

- Check migration of population from rural areas to urban areas.

- To boost the economy of the area.

- A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed between Gujarat, Maharashtra and the central government on May 3, 2010, that envisaged that Gujarat would get the benefit of the Par Tapi Narmada link project through en-route irrigation from the link canal and in the drought-prone Saurashtra Kutch region by way of substitution.

- The Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the project was prepared by the National Water Development Agency (NWDA) in 2015 and modified on the intervention of the Gujarat government, through letters the then chief minister wrote in 2016.

- The State Government had suggested to include the command area of five projects proposed, namely: Ugta, Sidhumber, Khata Amba, Zankhari and Khuntali; irrigate tribal areas en route right side of link canal by lift; lift irrigate tribal areas of Dang and Valsad districts directly from the reservoirs; explore possibilities of irrigation in the tribal areas of Chhota Udepur and Panchmahal districts from Narmada Main Canal on substitution basis; provide drinking water for all villages of Dang and Navsari districts and villages of Kaprada and Dharampur talukas of Valsad district and provide for filling up all possible tanks in the area under the project’s cover.

- The Gujarat government had, in December 2016, proposed providing a pipeline system instead of open canals to “avoid/minimise the land acquisition in tribal areas” as well as to reduce evaporation and seepage losses.

- According to a report by the NWDA, about 6065 ha of land area will be submerged due to the proposed reservoirs. A total of 61 villages will be affected, of which one will be fully submerged and the remaining 60 partly. The total number of affected families would be 2,509 of which 98 families would be affected due to the creation of the Jheri reservoir, the only one in Maharashtra, spread over six villages.

- In Gujarat, 793 families from 17 villages will be affected by the Kelwan reservoir, 563 families by the Dabdar reservoir across 11 villages, 379 families by Chasmandva reservoir spread over seven villages, 345 families would be affected by Chikkar reservoir across nine villages and 331 families would be affected due to Paikhed reservoir spread over 11 villages.

- The affected villages are located in Surgana and Peint talukas in Nashik and Dharampur taluka of Valsad, Vansda taluka of Navsari and Ahwa taluka of Dang districts in Gujarat.

- The surplus water proposed to be diverted through the estimated Rs 10,211 crore Par-Tapi-Narmada link project is expected to irrigate an area of 2,32,175 hectares, of which 61,190 ha is en route to the link canal.

- The command area of five projects on the left side of the canal as proposed by the Gujarat government is about 45,561 ha which will be irrigated by gravity through a link canal. The 36,200 ha on the right side will be by lift irrigation.

- The link project will take over 76710 ha under the command of the existing Miyagam branch canal of the Narmada canal system. The Narmada water thus saved will be used to irrigate nearly 23,750 ha of tribal land in Chhota Udepur district and 10,592 ha in Panchmahal district, on the right side of the Narmada Main Canal (NMC). About 42,368 ha area in the Saurashtra region will also be covered.

- The project aims to harness the excess water that flows into the sea by interlinking the rivers. This will also help in containing regular flood-like situations in the rivers in Valsad, Navsari, Surat and Bharuch.

- The idea behind the interlinking of rivers is that many parts of the country face problems of drought while many others face the problem of flooding every year.

- The Indo-Gangetic rivers are perennial since they are fed by rain as well as the glaciers from the Himalayas.

- The peninsular rivers in India are, however, not seasonal because they are rain-fed mainly from the south-west Monsoons.

- Due to this, the Indo-Gangetic plains suffer from floods and the peninsular states suffer from droughts.

- If this excess water can be diverted from the Plains to the Peninsula, the problem of floods and droughts can be solved to a large extent.

- Hence, the interlinking of rivers will bring about an equitable distribution of river waters in India.

- This project envisages the transfer of water from the water-excess basin to the water-deficient basin by interlinking 37 rivers of India by a network of almost 3000 storage dams. This will form a gigantic South Asian water grid.

- There are two components of this Project:

- Under the Himalayan component of the NRLP, there are 14 projects in the pipeline.

- Storage dams will be constructed on the rivers Ganga and Brahmaputra, and also their tributaries.

- The linking of the Ganga and the Yamuna is also proposed.

- Apart from controlling flooding in the Ganga – Brahmaputra River system, it will also benefit the drought-prone areas of Rajasthan, Haryana and Gujarat.

- This component has two sub-components:

- Connecting the Ganga and Brahmaputra basins to the Mahanadi basin.

- Connecting the Eastern tributaries of the Ganga with the Sabarmati and Chambal River systems.

- This component of the NRLP envisages the linking of the 16 rivers of southern India.

- Surplus water from the Mahanadi and the Godavari will be transferred to the Krishna, Cauvery, Pennar, and the Vaigai rivers.

- Under this component, there are four sub-component linkages:

- Linking Mahanadi and Godavari River basins to Cauvery, Krishna, and Vaigai river systems.

- Ken to Betwa river, and Parbati & Kalisindh rivers to Chambal River.

- West-flowing rivers to the south of Tapi to the north of Bombay.

- Linking some west-flowing rivers to east-flowing rivers.

- Interlinking rivers is a way to transfer excess water from the regions which receive a lot of rainfall to the areas that are drought-prone. This way, it can control both floods and droughts.

- This will also help solve the water crisis in many parts of the country.

- The project will also help with hydropower generation. This project envisages the building of many dams and reservoirs. This can generate about 34000 MW of electricity if the whole project is executed.

- The project will help with dry weather flow augmentation. That is when there is a dry season, surplus water stored in the reservoirs can be released. This will enable a minimum amount of water flow in the rivers. This will greatly help in the control of pollution, in navigation, forests, fisheries, wildlife protection, etc.

- Indian agriculture is primarily monsoon-dependent. This leads to problems in agricultural output when the monsoons behave unexpectedly. This can be solved when irrigation facilities improve. The project will provide irrigation facilities in water-deficient places.

- The project will also help commercially because of the betterment of the inland waterways transport system. Moreover, the rural areas will have an alternate source of income in the form of fish farming, etc.

- The project will also augment the defence and security of the country through the additional waterline defence.

- Project feasibility: The project is estimated to cost around Rs.5.6 lakh crores. Additionally, there is also the requirement of huge structures. All this requires a great engineering capacity. So, the cost and manpower requirement are immense.

- Environmental impact: The huge project will alter entire ecosystems. The wildlife, flora and fauna of the river systems will suffer because of such displacements and modifications. Many national parks and sanctuaries fall within the river systems. All these considerations will have to be taken care of while implementing the project. The project can reduce the flow of fresh water into the sea, thus affecting marine aquatic life.

- Impact on society: Building dams and reservoirs will cause the displacement of a lot of people. This will cause a lot of agony for a lot of people. They will have to be rehabilitated and adequately compensated.

- Controlling floods: Some people express doubts as to the capability of this project to control floods. Although theoretically, it is possible, India’s experience has been different. There have been instances where big dams like Hirakud Dam, Damodar Dam, etc. have brought flooding to Odisha, West Bengal, etc.

- Inter-state disputes: Many states like Kerala, Sikkim, Andhra Pradesh, etc. have opposed the river interlinking project.

- International disputes: In the Himalayan component of the project, the effect of building dams and interlinking rivers will have an effect on the neighboring countries. This will have to be factored in while implementing the project. Bangladesh has opposed the transfer of water from the Brahmaputra to the Ganga.

- Local solutions (like better irrigation practice) and watershed management, should be focused on.

- The government should alternatively consider the National Waterways Project (NWP) which “eliminates” friction between states over the sharing of river waters since it uses only the excess flood water that goes into the sea unexploited.

- The necessity and feasibility of river-interlinking should be seen on a case-to-case basis, with adequate emphasis on easing out federal issues.

- As per the report on ‘Composite Water Management Index’ published by the NITI Aayog (2018), “600 million Indians face high to extreme water stress and about two lakh people die every year due to inadequate access to safe water”. Besides alleviating the water crisis, the NRLP is expected to generate about 34 giga watts of additional hydropower.

- Be that as it may, since the severe water scarcity is already looming in most parts of the country, swift action is needed to link the rivers wherever possible jointly by the Centre and States to strengthen the water and food security, without creating an ecological disaster.

About International Day of Forests

About International Day of Forests

- The day is celebrated to raise awareness about the significance of different types of forests. The theme for 2022 is Forests and sustainable production and consumption.

- It is aimed at raising public awareness among diverse communities about the values, significance and contributions of the forests to balance the life cycle. Government networks and private organisations work together on this day every year to enlighten people about the importance of forests and the role they play in our ecology as well as the economy.

- On International Day of Forests, several countries across the world are encouraged to undertake local, national, and international efforts to organize activities involving forests and trees, such as tree-planting campaigns.

- The day reminds people to value and save forests and the importance of forests in the lives of living creatures. Forests also play an important role in providing food, water, and shelter for animals as well as human beings.

- Back in 1971, the 16th session of the Conference of the Food and Agriculture Organization, FAO, gave their consent to World Forestry Day. Later the United Nations General Assembly on 28th November 2012 had declared March 21 as International Day of Forests.

- The United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 21 March the International Day of Forests in 2012 to celebrate and raise awareness of the importance of all types of forests. Countries are encouraged to undertake local, national and international efforts to organize activities involving forests and trees, such as tree planting campaigns.

- The organizers are the United Nations Forum on Forests and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in collaboration with Governments, the Collaborative Partnership on Forests and other relevant organizations in the field.

- India’s definition of forest cover is in sync with that of the Kyoto Protocol.

- A “forest” has a minimum area of 0.05 to 1 ha (India has 1.0 ha minimum), with the tree crown cover percentage being more than 10 to 30 per cent (India has 10 per cent) and with trees having the potential to reach a minimum height of 2 to 5 m at maturity in situ (in India, it’s 2 m).

- The definition thus arrived at by India assesses forests as all lands, more than 1 hectare in area, with a tree canopy density of more than 10 per cent irrespective of ownership and legal status.

- Such lands may not necessarily be a recorded forest area.

- It also includes orchards, bamboo, palm etc.

- Forests cover 30 percent of the Earth's surface. They are sources of clean air and water. According to a UN study, forests can lift one billion people out of poverty. They can also create an additional 80 million green jobs.

- The UN agency on climate change, IPCC, revealed the deadly consequences of climate change across the world in the coming decades. So, this day becomes acutely significant to encourage leaders to muster the political will to address one of the most pressing challenges of our times by at least increasing the green cover at a time when the loss of agricultural land is occurring 30-35 times faster than previously estimated. Around 10 million hectares are lost every year, affecting poor communities around the world.

- Also, forests act as shields from zoonotic diseases. In fact, one out of three outbreaks of new and emerging diseases are linked to deforestation and other land-use changes.

- When we drink a glass of water, write in a notebook, take medicine for a fever or build a house, we do not always make a connection with forests. And yet, these and many other aspects of our lives are linked to forests in one way or another.

- Forest sustainable management and their use of resources are key to combating climate change, and to contributing to the prosperity and well-being of current and future generations.

- Forests also play a crucial role in poverty alleviation and in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Yet despite all these priceless ecological, economic, social and health benefits, global deforestation continues at an alarming rate.

- Wood helps to provide bacteria-free food and water in many kitchens, build countless furniture and utensils, replace materials as harmful as plastic, create new fibers for our clothes and, through technology, be part of the fields of medicine or the space race.

- It is vital to consume and produce wood in a more environmentally friendly way for the planet and its inhabitants. Let’s protect this easily renewable resource with sustainable management of forests.

- The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations that leads international efforts to defeat hunger. Our goal is to achieve food security for all and make sure that people have regular access to enough high-quality food to lead active, healthy lives.

- FAO’s Forestry Programme oversees more than 230 projects in 82 countries, with a total available project budget of USD 246 million (as of 2019). FAO is guided in its technical forestry work by the Committee on Forestry (COFO) and six regional forestry commissions.

- The FAO is composed of 197 member states. It is headquartered in Rome, Italy, and maintains regional and field offices around the world, operating in over 130 countries.

- It helps governments and development agencies coordinate their activities to improve and develop agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and land and water resources.

- It also conducts research, provides technical assistance to projects, operates educational and training programs, and collects data on agricultural output, production, and development.

- The FAO is governed by a biennial conference representing each member country and the European Union, which elects a 49-member executive council.

- The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) is implementing three major schemes for development of forest areas i.e. National Afforestation Programme (NAP) scheme, National Mission for a Green India (GIM) and Forest Fire Prevention & Management Scheme (FFPM).

- The overall objective of the National Afforestation Programme (NAP) scheme is ecological restoration of degraded forests and to develop the forest resources with peoples’ participation, with focus on improvement in livelihoods of the forest-fringe communities, especially the poor.

- NAP aims to support and accelerate the on-going process of devolving forest conservation, protection, management and development functions to the Joint Forest Management Committees (JFMCs) at the village level, which are registered societies.

- The scheme is implemented by three tier institutional setup through the State Forest Development Agency (SFDA) at the state level, Forest Development Agency (FDA) at the forest division level and JFMCs at village level.

- The major components of the scheme include afforestation under Seven plantation models, maintenance of previous years plantations and Ancillary Activities like soil and moisture conservation activities (SMC), fencing, overheads, monitoring and evaluation (M&E), micro-planning, awareness raising, Entry Point Activities (EPA) etc.

- The Scheme is demand driven and afforestation area is sanctioned on the basis of past performance, potential degraded forest land available for eco-restoration and availability of budget.

- The vision of creating Nagar Van Udyan Scheme is to develop at least one City Forest in each city having Municipal Corporation or Class 1 Cities to accommodate a wholesome health environment and contribute to the growth of clean, green, and sustainable India.

- Its objective is to create 200 City forests in the country and to create awareness about plants and biodiversity. Conservation education to the people who are unaware of the damage that can happen due to their ignorance in the conservation of nature.

- Waste management under Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, a mass movement initiated by the Prime Minister of India, Mr. Narendra Modi, in the year 2014. The Abhiyan motives lie in the cleanliness of the environment.

- He hopes to create a sense of sense of responsibility among the citizens to help achieve Mahatma Gandhi’s aim for Clean India. The main objective of Abhiyan is to recover resources for utilization through recycling and creating employment in the process.

- Project Tiger has been the most successful environmental project by the Government. Project Tiger was adopted in the year 1973 to improve the decreasing numbers of Tigers in India. It is a scheme sponsored by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change and assists the tiger states for tiger conservation.

- The objectives of the projects are to protect and restore habitat, monitor them day-to-day, eco-development for local people, and relocation of the people from the habitats of tigers.

- The Government of India initiated the National Wetland Conservation Programme (NWCP) to conserve and make acute use of wetlands in the country, therefore, preventing its further degradation. The scheme was introduced with the objective of undertaking extensive conservation measures in the wetlands that need immediate help.

- The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate change launched the Green Skill Development Programme in June 2017. Green skills include conserving and protecting the green of nature alongside creating awareness among the youth to develop skills and gain experience.

- In May 2018, during the launch of the GSDP mobile app, Harsh Vardhan, the Union Minister for Environment, forest, and climate change said that 2.25 lakh people will be employed through GSDP by the next year and about five lakhs will be employed by 2021.

- It provides assistance and guidance to the state board. CPCB advises the Central government in matters related to water purification and elimination of water pollution.

- CPCB lays down quality measures of water. It prepares manuals for the treatment and disposal of sewage and trade discharges.

- It compiles and collects data and provides a statistical analysis of water quality and pollution.

- It sets up laboratories for the analysis of water quality, sewage, or trade discharges.

- The Wildlife Act was one of the most prominent Acts enacted for protecting wild animals and birds. Control of wildlife was transferred from the State list to the Concurrent list in 1976, thus giving power to the Central government to enact this legislation.

- The Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 also included the Constitution of the Indian Board of Wildlife (IBWL), which actively took up the charge of setting up wildlife natural parks and sanctuaries.

- The main objective of the enactment of the Act was to put restrictions on hunting or poaching wildlife animals and birds. The Act includes rehabilitation of endangered or threatened species.

- Preservation of biological diversity by setting up sanctuaries and parks and granting permission to hunt the wildlife for specific purposes such as scientific research, scientific management, and collection of specimens for museums and zoological gardens, etc.

- Collaborating with NGOs to create awareness for the promotion of saving and preserving wildlife diversity. This Act is adopted by all the states except the state of J&K, they have their own sets of acts.

- The Forest Conservation Act comprises all types of forest including reserve forests, protected forests, or any forests irrespective of their ownership.

- The Forest Conservation Act, 1980 has ample provisions promoting the elimination of deforestation and stating to encourage afforestation in the non-forest areas. It has imposed restrictions on the de-reservation of the forest without any prior Central government approval and prohibits allotment of any forest land for non-forest purposes.

- Forest-dwelling tribal communities have rich knowledge and have good experience but their contribution mostly goes unnoticed and honored.

- Amended Forest Act, 1992: The Act made some provisions for allowing non-forestry activities with the prior approval of the central government.

- Wildlife sanctuaries and natural parks are entirely prohibited from being used for any exploration or survey without prior approval from the Central Government. Cultivation of tea, coffee, spices, rubber, palms, oil-bearing plants, and cash crops comes under non-forestry activities, therefore, are prohibited and are not allied in the forest lands.

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act provides prevention and control of any water-related pollution. It focuses on the maintenance and restoration of water quality on the surface and ground.

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 has set up two boards: Central and State. These boards are assigned with powers and functions to control pollution. The Act has been provided with funds, budgets, and accounts for these boards.

- The Act restricts the disposal of any poisonous, polluting matter in the flow of the water. The Act also includes punishment and fines for any violation of the provisions.

- Exposure to nature is beneficial and is important for the survival of living beings. It’s high time to focus on protecting natural resources and safeguarding the environment. The Government of India has done quite a remarkable job to combat the emerging deterioration in the conservation of nature but we still have to go a long way.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- Data from the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) (2019-20) shows female labour force participation at 22.8 percent, compared to a far higher 56.8 percent for men. The survey was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which since 2020 has caused the further shrinking of the country’s female workforce.

- Data from PLFS for the quarter of January-March 2021 shows that women’s presence in the workforce dropped to 16.9 percent following the first year of the pandemic, while for men it remained largely the same.

- Only 4.69 percent of India’s total workforce have undergone any formal skills training. Other countries have far higher proportions of their populations undergoing skills training: 68 percent in the UK; 75 percent in Germany; 52 percent in the US; 80 percent in Japan; and 96 percent in South Korea.

- In India, however, a higher percentage of women workers are part of the informal economy compared to men — 94 percent of women workers are in the informal sectors, working as daily-wage agricultural labourers, at construction sites, as self-employed micro-entrepreneurs, or engaged in home-based work.

- According to Labour Bureau data from 2013-14,[11] only 3.8 percent of India’s adult women had ever received vocational training at that time, compared to 9.3 percent of men. Of these women who did receive vocational training, 39 percent did not join the labour force following training.

- Studies suggest that by the next decade, 75 million women will join the workforce in India (Niti), with over 90 per cent of them employed in informal sectors. This necessitates an urgency to enable women to expand their learning opportunities and chart pathways for themselves, which could keep them off of exploitation, abuse and unequal pay at work.

- Innovative thinking and social restructuring need to be evolved to make a shift by bringing young females to formal education and training programmes and, thereby, the workforce. Raising women participation in the workforce can boost India’s GDP by 27 per cent.

- The use of technology, promotion of incubation space and setting up of upskilling centers would equip and enable women to participate in the ongoing fourth industrial revolution.

- In addition to vocational training, foundational and 21st-century skills are crucial to empower women in building a strong foundation for employment.

- Literacy alone is unlikely to translate into gainful employment, until and unless focused support is extended to the female labour force, particularly young women.

- What we need is a bouquet of women-centric enablement initiatives comprising socio-economic support, relevant skills, guaranteed jobs and investments to lower barriers and carve out an accessible gateway for women to enter into various sectors of the economy and contribute to India's progress.

- India is on the threshold of growth and development and is poised to become the third-largest economy of the world by 2030. Being a young nation, we are getting ready to reap the benefits of our demographic dividend. A Government of India skills gap analysis shows that by 2022, the country will need an additional 109 million skilled workers in 24 key sectors of the economy.

- The global Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development through its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) embody a roadmap for progress that is sustainable and leaves no one behind. Achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment is integral to each of the 17 goals. The Indian government is committed to the achievement of SDGs by 2030.

- Empowering women and girls and achieving gender equality requires concerted efforts of all stakeholders. A policy framework, encouraging and enabling women’s participation, should be constructed with an active awareness of the “gender-specific” constraints that face most women. Gender-responsive policies need to be contextually developed.

- Equal participation of women in the Indian economy is imperative to achieve our lofty goals of becoming an economic superpower. Some gaps and challenges lie ahead, but empowering our women force is also an opportunity and the potential for the country to grow more rapidly and at a pace which can fully harness our demographic dividend.

- There is no single policy measure that can address the complex issue of women’s participation in the workforce.

- Most women in India are employed in low-skill and low-paying work, with neither social protection nor job security. Their economic contribution is all but made invisible.

- Gender discrimination is more severe in the informal sector than in the formal sector, with women informal workers receiving less than half the male wage rate.

- Greater informality leads to lower incentives to acquire new skills, while employers prefer machinery over labour when faced with inadequately skilled workers.

- In the case of the female workforce, pervading informality is added to other challenges that keep them from participating in work – such as the burdens of family and caregiving, restrictive social norms, and limitations on mobility.

- There were hardly any women taking courses in sectors such as construction and real estate, transportation and logistics, electronics, IT hardware, the auto industry, or the pharma industry.

- Even the dropout rate for females, at an average of 23 percent across ITIs, has been a matter of concern. Gender bias norms around work, mobility, information, and access to networks have affected the uptake of the programmes.

- Women cited multiple challenges they faced while undertaking vocational training: travelling to the remote locations of ITIs; absence of adequate, functional toilets at the institutes; lack of counselling and orientation for course selection; difficulties in dealing with course work alongside family responsibilities; and the perception of ITIs as male-dominated, with many more male instructors than female.

- Programmes under ‘Skill India’, launched in 2015, have fallen short of expected outcomes. One of the reasons is the paucity of funds. The budgetary allocation for skilling has remained modest, with a large sum directed towards PMKVY, leaving little for the other schemes.

- The lack of diversity in skills training reflects the gender segregation of the job market.

- Relatively little fresh employment has been created within highly skilled occupations, while there have been large, absolute increases in employment in unskilled occupations.

- Despite receiving the maximum budgetary allocation, PMKVY has a poor placement record; moreover, many candidates are placed in poor quality jobs in the informal sector. It identified two crucial factors that inhibit women from taking up and keeping jobs. Both these issues are dictated by social norms:

- The most widely reported reason was that their families did not give them permission.

- Subsequently too, women who dropped out did so mainly due to family pressure, while men quit due to job-related discontent.

- Women also reported a reluctance to migrate. While female trainees were less likely both to receive job offers and accept them, the chances of them doing so was even lower if the jobs required them to move out of their place of residence.

- Families of female trainees expressed concern for the women’s safety when they were offered jobs outside their district or state.

- India’s skilling programmes are struggling to keep up with the demands of a changing and dynamic employment market.

- Whether agriculture, services, or industry, all sectors of the economy are embracing automation in varying degrees. It is estimated that up to 12 million women in India could risk losing their jobs to automation by 2030.

- Since 2009, the National Policy on Skill Development was formulated, there has been concerted support for policy-backed skill development initiatives.

- In 2015 the Union government launched the National Skill Development Mission, which in its policy document emphasises that women constitute half the demographic dividend and skilling could be the key to increasing their participation in the country’s labour force.

- To bridge the gap in skilling, various provisions have been made for women in skilling programmes. For instance, 30 percent of seats in Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) are reserved for women. There are 15,042 such ITIs across the country.

- There are also a few exclusive National Skill Training Institutes for Women, which offer trainings under two schemes: the Craftsmen Training Scheme (CTS) and the Craft Instructors’ Training Scheme (CITS). Eleven such institutes have been set up and eight more are in the pipeline.

- The flagship programme of MDSE—the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) which offers short-term skills training—pays close attention to the gender mainstreaming of skills.

- The Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushal Yojana (DDU-GKY), a placement-linked skills development programme for rural youth implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development, provides for a 33-percent reservation for women. DDU-GKY has trained 1,128,301 candidates so far, and about half the beneficiaries of the programme have been placed in jobs after obtaining their certification.

- The Skills Acquisition and Knowledge Awareness for Livelihood Promotion (SANKALP) scheme, implemented by MSDE in collaboration with the World Bank, has targets to increase the participation of women in short-term vocational training. It is a supporting programme for skill training schemes like PMKVY.

- The National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS), launched in 2016, follows the apprenticeship model for skilling and placement. It links courses under PMKVY and DDU-GKY with apprenticeship training to prepare candidates for the job market. The scheme had a placement record of 44 percent, according to a 2018 Standing Committee Report on Labour.

- The Jan Shikshan Sansthan, an old scheme under the Ministry of Human Resources Development, has since been revived under the MSDE. It focuses on skilling non-literate and school dropouts, especially women.

- There are a few successful initiatives by NGOs in training women for non-traditional jobs and connecting them to the job market. They include Azad Foundation’s Women on Wheels, where women are trained in professional driving; the Self Employed Women’s Association’s (SEWA) Karmika School for Construction Workers in Gujarat; the Archana Women’s Centre in Kerala which trains women in masonry, carpentry, electrical work and plumbing; and the Barefoot College International’s Enriche Programme in Rajasthan which trains women in digital literacy, STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) subjects and sustainable livelihoods like solar technology.

- A bottom-up approach to skilling could lead to better results. Such a strategy involves using local self-help group leaders to identify women workers with supportive families, and providing these women with relevant information to encourage them to take up skilling.

- A number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have, to some extent, filled the gap. They train women in jobs that help break stereotypes, thus giving them access to livelihoods that have been traditionally male-dominated, enabling them to earn more than in the jobs traditionally assigned to them (such as domestic service and caregiving).

- The demand for skilled workers is concentrated in cities, and men comprise over 80 percent of migrant workers in India. Providing migration support to women could improve skilling and employment outcomes.

- Public-private partnerships could be the way forward for inclusive digital skilling, especially for women. There are a few programmes already underway. Microsoft and the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC), in a public-private partnership, train more than 100,000 underserved women in digital skills.

- SAP India and Microsoft have also launched a joint skilling programme, TechSaksham, for 62,000 female students from underserved communities, to train them for technology-related careers. The programme has partnered with the All-India Council for Technical Education’s (AICTE) Training and Learning Academy-(ATAL) and the collegiate education departments of states to support professional development of faculty at participating institutes.

- For skilling to be effective for women in India, its training design has to be gender-sensitive. Skilling must be made bottom-up and sustainable. It cannot be viewed in isolation from the gendered realities of the labour market and prevailing social norms.

- Policies have to be gender-responsive to address the issues of recruitment and retention of women. They must be linked to awareness measures, to market needs, and coupled with post-placement support and welfare amenities.

- Childcare provisions can improve women’s participation in skilling programmes, along with safe transportation that addresses their mobility limitations.

- Skilling must integrate women into sectors that are dominated by men, which can help improve their incomes.

- There is also a need to integrate life skills, such as communication ability, decision-making capacity and self-confidence, into skilling programmes.

- Although life skills are essential for both men and women, in a country like India, women who acquire foundational and technical skills, often flounder when it comes to having confidence in decision-making. SEWA has been an early adopter of models of skilling that help girls and women grow into independent, well-rounded, confident leaders.

- Equipping women with employable skills are a far greater challenge than skilling men, as most women in India work low-skill and low-paying jobs in the informal economy. It is a gap that needs to be addressed urgently, as skilling can expand work opportunities for women and increase their participation in the workforce.

- However, skilling can provide women with occupational choices and expand their work opportunities. Studies have shown that skilling has a proven impact on workforce participation. Given the opportunity, many more women in India could join the workforce. An effective policy environment and support from the private sector can tackle the crisis.

About Namma Oor Thiurvizha

About Namma Oor Thiurvizha

- Namma Oor Thiruvizha, or the Festival of Our Land, being organised to symbolise the pride of Tamil culture.

- This event is a part of celebrations of the 75th Independence Day as ‘Suthanthira Thirunaal Amutha Peruvizha’.

- More than 400 artists from across the State will participate in the event organised by the Department of Art and Culture and Department of Tourism following Covid-19 guidelines.

- During the budget last year (2021-2022), the government had announced that a grand folk-art festival will be organised every year to promote traditional folk-art forms.

- It is a derivative of Chennai Sangam. While the original plan was to host it at the time of Pongal festival, it couldn’t be done due to Covid-19 restrictions. This will be a one-day festival and a decision regarding holding the festival in more places will be taken soon. Entry for the event will be free.

- When asked if traditional art forms will be part of government functions, the minister said all steps will be taken to promote them.

- Elaborate arrangements are being made to organise the festival which will feature instrumental music performances, dance and art performances, adventure shows and music.

- In a modern era, the Tamil Nadu government is taking all possible efforts and initiatives to remind the Tamil community about its roots and culture. The mega event symbolises the pride of Tamil culture.

- Independent yet together are the heart of Tamils that beat for the little joys they find in the festivals that the state proudly celebrates. It is a land that breathes in the natural aura of culture and tradition, a glimpse of which is seen in the rituals and the heartfelt worship people dwell their souls in.

- Followed by the Music and dance festival of Chennai which also applauds the classical form of dance and music.

- The festival will be organised every year by the government with the participation of a large number of artists.

- It helps to expose the hidden talent of the particular territory and gives them the opportunity to further harness their skill and search for employment opportunities in these as well.

- It will help to improve the state’s economy, including the influx of tourism.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- Kolkata is among eight megacities most vulnerable to disaster-related mortality, noted the recent United Nations (UN) report on climate change.

- The city in eastern India, along with eight other Asian cities, also run the “additional risk of subsidence due to sea-level rise and flooding.

- Six other megacities in Asia highly exposed to disaster-related deaths are Tokyo, Osaka, Karachi, Manila, Tianjin and Jakarta, according to IPCC.

- The Assessment Report 6 made several references about Kolkata that underline the city’s vulnerability to multiple climatic risks. It also warned about its lack of resilience in combating those risks.

- The report warned the number of people exposed to 1-in-100-year storm surge events is the highest in Asia. These include Guangzhou, Mumbai, Shenzen, Tianjin, Ho Chi Minh City, Kolkata, and Jakarta. It is projected that by 2050, without adaptation, the annual losses incurred in these cities will increase to approximately $32 billion (Rs 2.4 lakh crore).

- Cyclones in India are most frequent in West Bengal’s South 24 Parganas district, adjoining Kolkata, a recent report prepared by the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) pointed out.

- Kolkata lost a substantial portion of its green cover due to Cyclone Amphan that struck India’s east coast in May 2020, the UN report said. The estimated cost of the cyclone triggered losses to the tune of $13.5 billion (about Rs 1 lakh crore).

- Significant warming of the Bay of Bengal region caters to the increase of high-intensity cyclones in Bengal coast, which, in turn, are likely to affect Kolkata significantly.

- The eastern city is also highly vulnerable to extreme heat waves, according to the IPCC report. “On average, Kolkata will experience heat equivalent to the 2015 record heat waves every year.” In 2015, the heat wave killed 2,500 people in India. Kolkata, along with Delhi and Karachi, has a high drought risk.

- The drainage and sewage network in the Kolkata Metropolitan Area is sparse and not commensurate with its area of 1,851 square kilometres.

- Where the network exists, it is mostly comprised of a century-old drainage and sewage system. The drainage systems are divided into 25 drainage basins (catchment areas), and the entire metropolitan area is divided into 20 sewer zones (zones for the sewer network). “The sewer network in the Kolkata Municipal Corporation covers 55 per cent of the total area.”

- The report further reminded that “flooding in Kolkata is an annual feature during the monsoons” and added that “any past incidence of high intensity rainfall synchronised with high tide in River Hooghly has almost always resulted in water-logging in Kolkata”.

- The latest IPCC report corroborates data in its August 2021 publication (Working Group I) that also pointed to similar threats. The report had particularly warned about rising sea levels near Sunderbans, which is hardly 100 kilometres from the city.

- “A city like Kolkata, which remains located close to the coast, stands extremely threatened. The city, known for its high malaria and dengue cases, may suffer further as a result of changing climate. Incidences of malaria, dengue and other vector-borne diseases will increase.

- Urbanisation also contributed to a rise in the city’s temperature, with more than 80 per cent warming being generated within the city itself, the report said. It added that “urban centres and cities were warmer than the surrounding rural areas due to the urban heat island effect”.

- The heat island effect can cause temperatures in urban areas to be several degrees higher than the countryside due to high population densities, heat from vehicular exhaust and the use of ACs, dark roads that absorb solar radiation, tall buildings that block wind flow and the lack of sufficient open green spaces.

- Urban heat island effect arises from several factors, including reduced ventilation and heat being trapped as tall buildings are closely packed in a small area; heat generated from human activities; heat-absorbing properties of concrete and other urban building materials; and limited amount of vegetation.

- Kolkata has all the required tell-tale elements of a highly unplanned city. It has high concretisation and extremely limited vegetation.

- Monsoon has become erratic and we are witnessing a sea change in the monsoon season pattern, once considered to be the most stable.

- The groundwater of the city and elsewhere in Bengal is dangerously depleted. The recharging of groundwater is dependent on the monsoon.

- Climate change is caused by excessive emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other Greenhouse Gases (GHG) like methane. These gases create a blanket around the atmosphere and trap heat, thereby warming our oceans and land surfaces.

- Science is now unequivocal that GHG emissions caused by human activities since the Industrial Revolution are causing climate change. These human activities include generation of electricity from fossil fuels (e.g., coal-fired power plants), emissions from transport (cars, buses, trucks, or anything that runs on petrol and diesel) and residential sector. Agriculture also causes emissions, mostly in the form of methane gases.

- Kolkata can still combat the ill-effects of climate change if it seeks appropriate solution measures.

- Green and blue infrastructure needs to be conserved in Kolkata. While green infrastructure (urban greenery) will help the city in withstanding climate risks like warming and impacts linked to that, blue infrastructure, which refers to protecting and enriching waterbodies, lake systems, wetlands and rivers across the city, is also important in terms of climate resilience.

- Preserving wetlands, River Hoogly and water bodies is a key to the city's survival. “Kolkata is a natural sponge city but unfortunately, the sponge is getting increasingly encroached upon.”

- The city and state administration should include climate change adaptation issues in all the major development activities of the city.

- The architecture planning of the buildings in the city also needs a strong look as the city has turned into a heat island. Kolkata’s average temperature has increased most at global benchmark in the last six decades till 2018, they cited another recent IPCC report.

- Catalyzing effective capital reallocation and new financing structures, including through scaling up climate finance; developing new financial instruments and markets, including voluntary carbon markets; deploying collaborations across the public and private sectors; and managing risk to stranded assets.

- Managing demand shifts and near-term unit cost increases for sectors through building awareness and transparency around climate risks and opportunities, lowering technology costs with R&D, nurturing industrial ecosystems, collaborating across value chains to reduce or pass-through cost increases from the transition, and sending the right demand signals and creating incentives for the transition.

- Establishing compensating mechanisms to address socioeconomic impacts, through economic diversification programs, reskilling and redeployment programs for affected workers, and social support schemes.

- Define decarbonization and offsetting plans and update them as competitive, financial, and regulatory conditions change.

- Integrate climate-related factors into key business decisions for strategy, risk management, finance and capital planning, R&D, operations (including supplier management and procurement), organizational structure and talent management, pricing, marketing, and investor and government relations.

- Governments and multilateral institutions could consider the use of existing and new policy, fiscal, and regulatory tools to establish incentives, support vulnerable stakeholders, and foster collective action. Public-sector organizations have a unique role in managing uneven effects on sectors and communities.

- Governments could establish multilateral and government funds to support low-carbon investment and manage stranded-asset risk.

- Institute reskilling, redeployment, and social-support programs for workers and manage negative effects on lower-income consumers.

- Choose a utility company that generates at least half its power from wind or solar and has been certified by Green-e Energy, an organization that vets renewable energy options.

- Green transition: Investments must accelerate the decarbonization of all aspects of our economy.

- Green economy: making societies and people more resilient through a transition that is fair to all and leaves no one behind.

- Invest in sustainable solutions: fossil fuel subsidies must end and polluters must pay for their pollution.

- Kolkata, a megacity in India, has been singled out as one of the urban centres vulnerable to climate risks. Modest flooding during monsoons at high tide in the Hooghly River is a recurring hazard in Kolkata. More intense rainfall, riverine flooding, sea level rise, and coastal storm surges in a changing climate can lead to widespread and severe flooding and bring the city to a standstill for several days.

- High resolution spatial analysis provides a roadmap for designing adaptation schemes to minimize the impacts of climate change. The modelling results show that de-silting of the main sewers would reduce vulnerable population estimates by at least 5 %.

About National Judicial Infrastructure Authority of India

About National Judicial Infrastructure Authority of India

- The Chief Justice of India will set up of National Judicial Infrastructure Authority of India (NJIAI) for arrangement of adequate infrastructure for courts, as per which there will be a Governing Body with Chief Justice of India as Patron-in-Chief.

- NJIAI could work as a central agency with each State having its own State Judicial Infrastructure Authority, much like the National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) model.

- It has also been suggested that the Chief Justice of India could be the patron-in-chief of the NJIAI, like in NALSA, and one of the Supreme Court judges nominated by the Chief Justice could be the executive chairman.

- The other salient features of the proposal are that NJIAI will act as a Central body in laying down the road map for planning, creation, development, maintenance and management of functional infrastructure for the Indian Court System, besides identical structures under all the High Courts.

- The proposal has been sent to the various State Government/UTs, as they constitute an important stakeholder, for their views on the contours of the proposal to enable taking a considered view on the matter.

- But, unlike NALSA which is serviced by the Ministry of Law and Justice, the proposed NJIAI will be placed under the Supreme Court of India.

- In the NJIAI there could be a few High Court judges as members, and some Central Government officials because the Centre must also know where the funds are being utilised.

- As far as the Centrally Sponsored Scheme for the Development of Infrastructure Facilities for Judiciary is concerned, the primary responsibility of development of Infrastructure facilities for judiciary rests with the State Governments.

- The current fund-sharing pattern of the CSS stands at 60:40 (Centre: State) and 90:10 for the eight north-eastern and three Himalayan States. The Union Territories get 100% funding.

- Similarly, in the State Judicial Infrastructure Authority, in addition to the Chief Justice of the respective High Court and a nominated judge, four to five district court judges and State Government officials could be members.

- The High Courts are independent of the Supreme Court. The only time when the Supreme Court comes in the picture is the appointment of judges of the High Courts.

- The primary responsibility of development of infrastructure facilities for judiciary rests with the State Governments.

- The Indian judiciary’s infrastructure has not kept pace with the sheer number of litigations instituted every year. A point cemented by the fact that the total sanctioned strength of judicial officers in the country is 24,280, but the number of court halls available is just 20,143, including 620 rented halls.

- Also, there are only 17,800 residential units, including 3,988 rented ones, for the judicial officers.

- As much as 26% of the court complexes do not have separate ladies' toilets and 16% do not have gents' toilets. Only 32% of the courtrooms have separate record rooms and only 51% of the court complexes have a library.

- Only 5% of the court complexes have basic medical facilities and, only 51% of the court complexes have a library. While the pandemic has forced most of the courts to adopt a hybrid system — physical and videoconferencing mode — of hearing, only 27% of the courtrooms have a computer placed on the judge’s dais with videoconferencing facility.

- Of a total of ?981.98 crore sanctioned in 2019-20 under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) to the States and Union Territories for development of infrastructure in the courts, only ?84.9 crore was utilised by a combined five States, rendering the remaining 91.36% funds unused.

- This underutilisation of funds is not an anomaly induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The issue has been plaguing the Indian judiciary for nearly three decades when the CSS was introduced in 1993-94.

- Judicial Independence / Financial autonomy: NJIAI makes the judiciary more fiscally independent from the Executive. Therefore, it can address judicial needs quickly.

- Expert Project Monitoring and Evaluation: NJIAI can be the part of the answer to complexities ensuring entrustment of Project Monitoring & Evaluation (PME) function to the experts available across the nation or even beyond.

- Bringing Standardisation: NJIAI would bring the uniformity and standardisation required to revolutionise judicial infrastructure

- Ensuring sufficient funding for Legal Services Authorities: Most of the State Legal Services Authorities are severely understaffed and are dependent on grants from National Legal Services and State Law Departments. The fiscal plight of Legal Services Authorities has a direct bearing on the availing of legal services by the beneficiaries. Overall financial independence of the judiciary alone can ensure the independence of the Legal Services Authorities.

- Reducing Pendency of cases: Strengthening the judicial infrastructure is the most important tool to reduce pendency of cases.

- Judicial infrastructure includes the physical premises of courts, tribunals, lawyers’ chambers, and so on. It also involves the digital and human resources infrastructure, including the availability of all the resources that are essential to ensure timely dispensation of justice.

- The positive correlation between adequate judicial infrastructure and productivity in justice delivery is empirically well-established. Adequate and quality judicial infrastructure are the basic pre-requisite for judges, lawyers, and judicial officers to efficiently perform their responsibilities while dispensing justice.

- According to the National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms, adequacy of judicial infrastructure is a pre-condition for reducing delay and backlogs in cases.

- The Supreme Court-constituted National Court Management System (NCMS) says that there is a direct connection between physical infrastructure, personnel infrastructure, digital infrastructure, and pendency.

- The NCMS plan highlights how infrastructure can fulfil goals such as providing optimum working conditions to increase efficiency.

- Criticality of adequate judicial infrastructure, particularly the digital, was very much felt during the course of the pandemic when courts were forced to opt for virtual mode. \

- With only one-third of lower courts having proper digital facilities—computer at judge’s dais with video-conferencing facility—justice delivery suffered a major blow.

- The COVID-19-induced disruptions, since March 2020, have pushed the pendency of cases to 19 percent, taking it to a record 4.4 crore. The most direct outcome of slow justice delivery is felt by the poorest and socially marginalised groups.

- The infrastructure problems in judiciary must be seen in the context of the lack of specific budgeting for the judicial branch, which is a standard practice in most democracies. The long and historical neglect of judiciary has resulted in inadequate institutional attention.

- This is clearly evident in the budgetary allocations to the judicial branch, a critical wing of the governance. Even after more than seven decades of independence, the budgetary allocations, including states, are still below 1 percent of the GDP.

- According to the recently released India Justice Report, between 2011-12 and 2015-2016, India’s annual average spending on the judiciary was just 0.08 percent of the GDP. While this has slightly improved with Centre increasing allocation—13th and 14th Finance Commissions—this remains to be an area of serious concern.

- Plus, the allocation from the Union Budget for the judiciary also remains inadequate and inconsistent. For instance, at a time when pendency of cases has grown astronomically and judicial infrastructure is not able to keep pace with the pressure, there was a steep cut—from INR 990 crore in 2019-2020 to INR 762) in funds for the creation of judicial infrastructure.

- Finance is not the sole reason for the current crisis. Under utilisation of funds meant for specific judicial infrastructure projects does not help either. In fact, over the last few years, the Central government has poured money under the centrally sponsored scheme (CSS) to address the infrastructure woes at the lower judiciary.

- Between 1993–2020, the centre has released INR 7,460.24 crore to the states to spend on improving district courts. This excludes 40 percent of states' share as part of the Central scheme. However, a large chunk of the allocated money goes unspent, eventually lapses, year after year.

- As per the CSS terms and conditions, states have to contribute 40 percent matching grant and most states fail to fulfil this commitment for a variety of reasons. Beyond the matching contribution, in general states have shown lukewarm response to this critical need. For instance, other than Maharashtra, which sanctioned 2 percent, every state in India has allocated less than 2 percent from their budgets towards judicial infrastructure.

- While the respective high courts have power to sanction district courts and related infrastructures, the decisions with regards to the implementation including the allocation of land, permission for the complex are undertaken by the state governments in consultation with respective high courts.

- This consultation and coordination are tedious and very time consuming. Most importantly, with states busy in more pressing priorities and high courts in their own day-to-day dispensing of justice, often projects have no real takers.

- Infrastructure projects inevitably include tedious processes such as procurement, tendering and auditing of building contracts. And judges cannot be expected to do a better job than other experts.

- Judges cannot sit over the drafting of RFPs (Request For Proposals) and tenders, negotiate with state governments for land allotments and conduct site inspections to monitor the progress of building construction.

- Parliament does not have sufficient power to force states to fund the NJIAI.

- Issues are also being raised about fixing the accountability of the funds spent by NJIAI.

- The proposed body is intended to monitor and address the issues of delay in land allotment, funds diversion for non-judicial purposes, evasion of responsibilities by the high courts and trial courts, amongst others. While the NJIC has lofty goals—a detailed blueprint is still not out.

- Some analysts have already raised strong doubts about its necessity and the roles it desires to play. For them, centralisation of powers under a new body would go against the principles of federalism. The NJIC cannot force the states to spend more or concede powers to a new body.

- Further, infrastructure projects, particularly under CSS funding, have tedious processes involving considerable paper works between the Centre and states, then there are issues of coordination on land acquisition, tendering, and award of contract, site inspections so on so forth. This would require considerable time and effort on the part of NJIC.

- While these are pertinent issues to ponder, we must recognise why the CJI is pressing for an intervention that requires ‘extraordinary’ measures. We have a situation in which neither the Centre nor the states have shown any genuine interest beyond ritual financial allocations.

- As past experiences of executing infrastructure projects show, there is no serious ownership from the states and district levels officials to complete these critical projects in a time-bound manner.

- Many projects are caught up in the institutional turf wars and often crucial issues like land allocations take many years delaying the project commencement. What complicates the matter is that since these projects are funded through CSS scheme, they have to follow a tedious process of paperwork between the centre and states.

- Projects are mostly carried out in an ad hoc manner without a clear timeline. This calls for a centrally coordinating agency that can monitor the works on a real time basis apart from empowering agencies involved in the execution of projects.

- Key issues like land allocations, tendering, and award of contract, site inspections require active coordination amongst multiple entities. This is where the NJIC can make critical intervention and open the doors for speedy resolution.

- There is a need for need for “financial autonomy of the judiciary” and creation of the NJIAI that will work as a central agency with a degree of autonomy.

- While the fear of centralisation and top-down interventions emerging from the NJIC have some basis, this can be greatly reduced by having a corporation at each state involving respective high court and state and district level officials. However, the fog of doubts can be cleared once the blueprint of NJIC is out in public. While one may debate about the nature and mode of functioning of such an entity, there is little denying the judicial infrastructure needs a big push.

- Since 1952, the Govt. of India also started addressing to the question of legal aid for the poor in various conferences of Law Ministers and Law Commissions.

- In 1980, a committee at the national level was constituted to oversee and supervise legal aid programmes throughout the country under the Chairmanship of Hon. Mr. Justice P.N. Bhagwati then a Judge of the Supreme Court of India. This Committee came to be known as CILAS (Committee for Implementing Legal Aid Schemes) and started monitoring legal aid activities throughout the country.

- The introduction of Lok Adalats added a new chapter to the justice dispensation system of this country and succeeded in providing a supplementary forum to the litigants for conciliatory settlement of their disputes. In 1987 the Legal Services Authorities Act was enacted to give a statutory base to legal aid programmes throughout the country on a uniform pattern.