- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

Mar 24, 2022

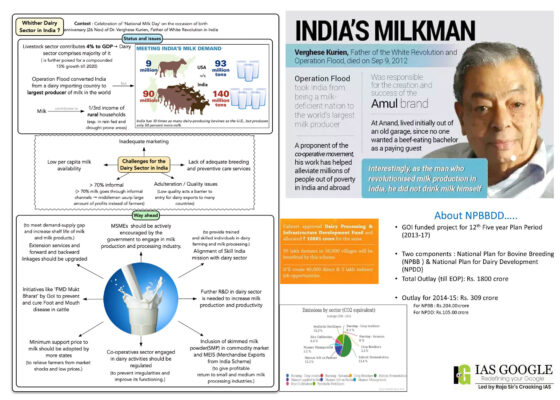

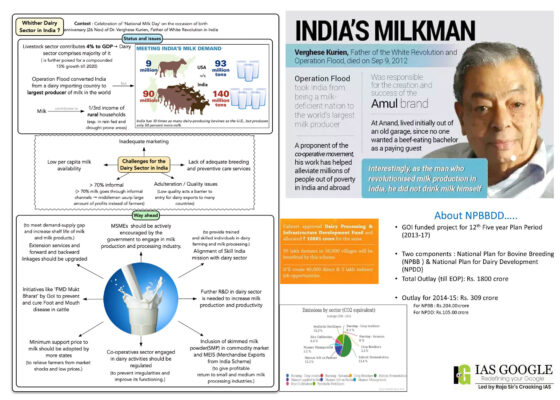

NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR DAIRY DEVELOPMENT

Under the National Programme for Dairy Development (NPDD) scheme, so far, 12.26 lakh farmer-members have been brought under the ambit of dairy cooperative network.

What is the Current State of the Dairy and Livestock Sector?

What is the Current State of the Dairy and Livestock Sector?

About Unnat Jyoti by Affordable Light Emitting Diode (LED) for All (UJALA)

About Unnat Jyoti by Affordable Light Emitting Diode (LED) for All (UJALA)

What is a Hypersonic Missile?

What is a Hypersonic Missile?

About Blue Economy

About Blue Economy

Findings of Minamata Convention (COP-4)

Findings of Minamata Convention (COP-4)

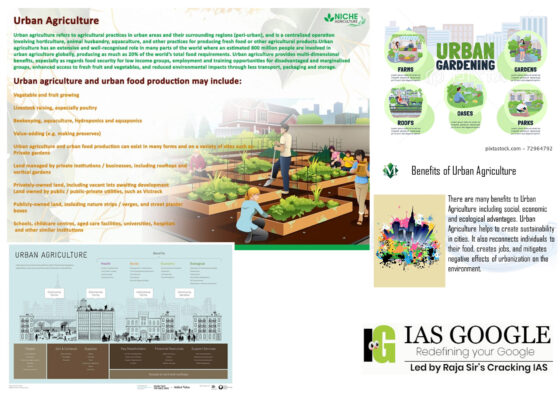

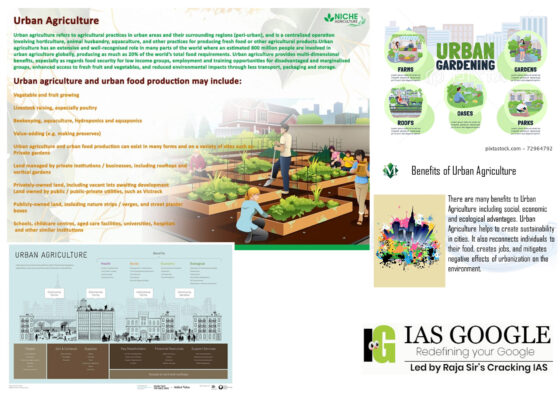

About Urban Agriculture in India

About Urban Agriculture in India

Genesis:

Genesis:

What is the Current State of the Dairy and Livestock Sector?

What is the Current State of the Dairy and Livestock Sector?

- Dairy is the single-largest Agri commodity in India. It contributes 5% to the national economy and employs 80 million dairy farmers directly.

- A revival in economic activities, increasing per capita consumption of milk and milk products, changing dietary preferences and rising urbanisation in India, has driven the dairy industry to grow by 9-11% in 2021-22.

- The livestock sector has grown at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 8.15% over the last five years ending 2020.

- Growth in the liquid milk segment, which accounts for over half of the dairy industry, is likely to remain stable (6-7%).

- The organised dairy segment, which accounts for 26-30% of industry (by value), has seen faster growth, compared to the unorganised segment.

- The National Programme for Dairy Development (NPDD) scheme was launched by the Government of India.

- The NPDD scheme is designed to provide technical and financial assistance for the dairy development and thereby creating any infrastructure related to the processing, production, marketing and procurement by the milk federation/unions while extending their activities by providing training facilities to the farmers.

- This scheme is implemented with the view to dairying activities in a scientific and holistic manner and integrate milk production so as to attain higher levels of milk production and its productivity, ultimately to meet the increasing demand for milk in the country.

- Dairying and its other activities have become a very important secondary source of income for millions of rural families and have the most important role in providing income-generating opportunities and employment opportunities particularly for marginal and women farmers as most of the milk that is produced by animals reared by small, marginal farmers and landless labours.

- The NPDD scheme aims to enhance the quality of milk and milk products and increase share of organized milk procurement.

- The scheme has two components:

-

- Component 'A' focuses towards creating/strengthening of infrastructure for quality milk testing equipment as well as primary chilling facilities for State Cooperative Dairy Federations/ District Cooperative Milk Producers’ Union/SHG run private dairy/Milk Producer Companies/Farmer Producer Organisations. The scheme will be implemented across the country for a period of five years from 2021-22 to 2025-26.

- Component 'B' (Dairying Through Cooperatives) provides financial assistance from Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) as per project agreement already signed with them.

- It is an externally aided project, envisaged to be implemented during the period from 2021-22 to 2025-26 on pilot basis in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar initially with the objective of creation of necessary dairy infrastructure for the purpose of providing market linkages for the produce in villages and for strengthening of capacity building of stake-holding institutions from village to State level.

- National Programme for Dairy Development (NPDD) will be implemented throughout the country from 2O2l-22 to 2O25-26 and will continue till 2027-28.

- The committed liabilities of ongoing NPDD scheme approved till 31.03.2021 shall be met under the revised scheme during first two years i.e., 2O21-22 & 2022-23 as per administrative approval issued at the time of approval of respective projects.

- Further, the committed liability to be created under above sub-schemes during the implementation period from 2O2I-22 to 2025-26, will be met through budgetary support during next two years i.e., 2026-27 &2027-28.

- To create and strengthen infrastructure for quality milk including cold chain infrastructure linking the farmer to the consumer;

- To provide training to dairy farmers for clean milk production; To create awareness on Quality & Clean Milk Production;

- To support research and development on Quality milk and milk products

- To strengthen and create the necessary infrastructure for the production of quality milk including the creation and development of cold chain infrastructure that will enhance the linkage between the farmers and their consumers.

- To strengthen and create the infrastructure required for the production, procurement, marketing and processing of milk.

- To create appropriate training infrastructure and facilities for the training of dairy farmers.

- To strengthen the dairy Producer Companies/cooperative societies at the village level

- To increase the production of milk by providing the most needed technical input services like mineral mixture and cattle feed, etc; to assist the rehabilitation potential and viable milk unions/federations.

- National Dairy Plan Phase-I (NDP-I) will cover the case of States (i.e, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar, Gujarat, Karnataka, Haryana, Kerala, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh).

- Implementation of NPBBDD will be done throughout the country.

- Central governmental assistance will be provided for the project and will be restricted to a total of Rs.15 crores per District.

- Any form of assistance provided for the “technical input services” will be subject to a ceiling of 15% of its project cost.

- For milk powder plants, the central grant per district will be limited to an amount of Rs.5 crores per district.

- The central grant for the establishment of milk powder plants will be limited to dairy cooperatives only.

- For the establishment/up gradation of milk powder plant of 30 metric tonnes capacity, surplus milk from milk shed that covers a cluster of districts may be pooled together to ensure the economic viability of the milk powder plant.

- Any assistance for the cattle induction shall be allowed only for BPL families, Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes.

- The subsidy for Cattle Induction will be restricted to a total of 50% in all cases except for the women farmers.

- The Cost of calculating the subsidy shall include: cost of cattle, animal insurance and transportation cost.

- The Cattle Induction will be subjected to a maximum ceiling of 10% of the total project cost.

- The assistance of manpower and skill development will be provided for setting up and/or upgrading a Training Centre for skill development. The total assistance under this component shall not be more than Rs.75 lakh or 5% of the total project cost, whichever is lower.

- The detailed Planning and Monitoring will be limited to 5% of the project cost.

- The subsidy element for cattle induction will have a maximum ceiling of 75% cost for women milk producers.

- Necessary assistance for Information and Communication Technology networking shall be subject to a maximum ceiling of 10% of the project cost.

- Any assistance for Working Capital shall be restricted to the total value of “21 days milk procurement”, as projected in the terminal year of the Project.

- The rehabilitation assistance as the central grant will be restricted to a ceiling of Rs.5 Crores.

- Doorstep Veterinary Emergence and Health Services at MPCS around 18 Lakh Artificial Insemination (AI) are done per year.

- Cattle feed subsidy Rs.2-4/kg given (will be revised every month according to current market rates)

- The Mineral mixture is supplied to the milk producers at a subsidy of Rs.25 per Kg.

- Periodical animal health camps are conducted in villages for mass deworming and to treat infertility cases in almost all district milk unions.

- Green fodder and fodder slips are provided to milk producers through fodder cultivation in union land.

- FMD vaccinations carried out twice every year in coordination with the Animal Husbandry Department, covering around 17 lakh animals under cooperative ambit in Tamil Nadu.

- Regular training is given to milk producers and village level workers in training centres.

- The profits earned by the district unions are shared with the milk producers by giving incentive which ranges from 60 paise per litre to Rs.1.60 per litre.

- Whenever the society earns any sort of profit, 50% of profit is ‘ploughed back’ to the milk produced as mentioned in the by-laws of the Milk Producers Cooperative Societies.

- Bulk Milk Cooler (BMC) is installed, when necessary, as per the request of the producers and the budgeting done under this scheme.

- The Dairy Cooperatives of India commissioned a large number of dairy processing plants during the Operation Flood that lasted till 1996.

- Up until now, most of these plants have never been re-developed or expanded after that. With operations continuing with old and obsolete technologies in these plants, the scope to improve efficiency and increase production is hard to achieve.

- Therefore, the Government of India announced the Dairy Processing and Infrastructure Development Fund (DIDF) under the NABARD with an estimated budget of INR 8,00 through the Union Budget 2017-18. This article talks about the important aspects and essentials of the DIDF.

- To modernise the milk processing plants and their machinery.

- To create additional infrastructures that specifically cater to the goal of processing more milk.

- To increase the overall milk processing capacity, that in turn, will increase the value addition, and by increasing the production of dairy products.

- To increase efficiency in dairy processing plants and producers that are owned and controlled by dairy institutions. Hence, enabling the optimum value of milk to milk producing farmers and increasing the supply of quality milk to consumers.

- To help the producer-owned-and-controlled institutions increase their share of milk production, thereby offering more significant opportunities of ownership, management and access to markets, to rural milk producers in the organised milk market.

- To assist the producer-owned-and-controlled institutions to have a stronghold in the organised milk market, strive as a dominant player, and to make increased Price Realisation to milk producers.

- Modernisation and creation of new milk processing facilities.

- Re-development and establishment of new manufacturing facilities for Value-Added Products.

- Infrastructure to maintain milk and other products at various optimum temperatures.

- Setting up of electronic milk testing equipment.

- Any other activities, decided by the Government of India in consultation with the relevant stakeholders, concerning the dairy sector and aims to contribute to the current objectives of the DIDF.

- The scheme follows a funding support pattern which will be in the form of an interest-bearing loan.

-

- Loan Component: Maximum of 80%

- End-borrower’s component: Minimum of 20%

- The tenure of the loan would be a maximum of 10 years from the date of the first release of funds. This would include the Moratorium Period of a maximum of 2 years on the repayment of the principal amount only. The Moratorium Period would be for the relevant project, and not for each release.

- The rate of interest would be 6.5% per annum for the end-borrower, which is currently set by the NDDB. The same would be effective throughout the repayment period. Therefore, interest will be calculated on a daily product basis, without compounding.

- The end-borrower is required to pay a commitment charge of 2% per annum with applicable taxes on the cumulative difference if the cumulative disbursement at the end of a quarter is below 90% of the pre-approved cumulative draw-down schedule. The rates may differ and will be conveyed by the NDDB as required. This charge would be levied from the start of the next quarter up until the differential amount is withdrawn.

- The end-borrower will be required to provide a State Government Guarantee for the repayment of the loan offered by the DIDF. However, this condition may be relaxed in situations where the end-borrower has enough collateral security. For cases such as these, the NDDB, in consultation with the NABARD, would examine the same and approval would be given as required.

- Loans availed from any other financial institutions or banks for projects under execution will be considered as loan swapping under the DIDF scheme subject to certain pre-conditions that have to be fulfilled.

- An eligible end-borrower must obtain a No-Objection Certificate (NOC) from the concerned financial institutions or funding agencies.

- The end-borrower will have to qualify for all the eligibility criteria defined under the DIDF scheme.

- No cases or disputes with respect to projects under consideration must be pending in the court of law.

- As per the terms and conditions of the DIDF Scheme, the reassessment of the project cost must be estimated along with procurement procedures and viability.

- Assessment of capability of the end-borrower to provide adequate security includes a guarantee from the State Government.

- There is an excessive number of unproductive animals which compete with productive dairy animals in the utilisation of available feeds and fodder.

- The grazing area is being reduced markedly every year due to industrial development resulting in a shortage of supply of feeds and fodder to the total requirement.

- Ever increasing gap between demand and supply in feeds and fodder limits the performance of dairy animals. Moreover, the provision of poor quality of forage to dairy cattle restricts animal production system.

- The low capability of purchasing feeds and fodder by the small and marginal farmers and agricultural labourers engaged in dairy development results in inadequate feeding.

- Non-supplementation of mineral mixture results in mineral deficiency diseases. High-cost Feeding reduces the profits of the dairy industry.

- Late maturity, in most of the Indian cattle breeds, is a common problem. There is no effective detection of heat symptoms during oestrus cycle by the cattle owners. The calving interval is on the increase resulting in a reduction in efficiency of animal performance.

- Diseases causing abortion lead to economic loss to industry. Mineral, hormone and vitamin deficiencies lead to fertility problems.

- A vigorous education and training programmes on good dairy practices could result in the production of safe dairy products, but to succeed they have to be participative in nature.

- In this regard, education and training of all the employees is essential so that they understand what they are doing and develop a sense of ownership.

- However, developing and implementing such programs in the dairy sector requires a strong commitment from the management, which at times is a stumbling block.

- Veterinary health care centres are located in far off places. The ratio between cattle population and veterinary institutions is wider, resulting in inadequate health services to animals.

- No regular and periodical vaccination schedule is followed, regular deworming programme is not done as per schedule, resulting in heavy mortality in calves, especially in buffalo. No adequate immunity is established against various cattle diseases.

- Many cattle owners do not provide proper shelter for their cattle leaving them exposed to extreme climatic conditions. Unsanitary conditions of cattle shed and milking yards lead to mastitis conditions.

- Unhygienic milk production leads to a reduction in storing quality and spoilage of milk and other products.

- Dairy farmers are not getting remunerative prices for milk supply. Due to the adoption of extensive crossbreeding programme with Holstein Friesian breed, the fat content of crossbreed cow's milk is on the declining condition and low price is offered as the milk price is estimated on the basis of fat and solid non-fat milk content.

- There is also a poor perception of the farmers, due to lack of marketing facilities and extension services, towards commercial dairy enterprise as an alternative to other occupations.

- This sector plays an important role in achieving food security, reducing global poverty, generating employment opportunities for women, and providing a regular source of income for rural households.

- In developing economies, landless and poor farmers are actively involved in dairying as an essential means of livelihood. According to the FAO 2018 report, more than 500 million impoverished people depend mainly on livestock, and many of them are small and marginal dairy farmers.

- Additionally, dairy development helps in boosting rural economic growth and empowering rural women. Moreover, 160 million children around the world receive benefits from milk through school feeding programmes.

- The dairy sector plays a vital role in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — especially SDG 1-No poverty, SDG 3-Good health, SDG 5-Gender equality, SDG 8-Good jobs and economic growth, and SDG 10-Reduced inequalities — and it helps in improving lives and transforming the global economy.

- Apart from being an important sector globally, dairying is equally important in developing economies like India, for providing nutrition support, reducing rural poverty, inequity, ensuring food security for millions of rural households, and enhancing economic growth, particularly in rural areas.

- The livestock sector contributes about 4.11 per cent to India's GDP and 25.6 per cent towards total agriculture GDP, whereas the dairy sector claims a major share by contributing 67per cent to total livestock output.

- This sector also provides self-employment opportunities, particularly for women and economically disadvantaged groups. Annually, 8.4 million small and marginal farmers depend on the dairy sector for livelihood, both directly and indirectly, out of which 71 per cent are women, thus demonstrating that the sector plays a vital role in women empowerment and inclusive growth.

- Dairying helps in equitable distribution of income and employment among the rural farming households, thereby reducing the disparity in holding of resources by the rural communities.

- Dairying in India is an occupation of small farmers. Over 60 percent of close to 11 million farmer members in about 100,000 village milk cooperatives all over the country are small, marginal and even landless producers. Dairying has not meant just producing milk leading to India emerging as the largest milk producer in the world. Dairying has provided livelihoods to millions of the poorest in our country and for many it is the sole source of livelihood, bringing cash into their hands, twice a day every day of the year.

- Improvement in livestock production is important for increasing the income of marginal and small farmers and landless laborers, given the uncertainties of crop production. The sector needs focused attention particularly in drought prone areas where there is all the more need to add to the incomes of the farmers.

- Promotion of dairying as a viable enterprise in the remote rural areas of the country can boost rural income and employment to a great extent. This can go a long way in removing poverty, unemployment and violence emanating from the rural areas of the country.

- The National Dairy Development Board's (NDDB) creation is rooted in the conviction that our nation's socio-economic progress lies largely on the development of rural India.

- The Dairy Board was created to promote, finance and support producer-owned and controlled organisations. NDDB's programmes and activities seek to strengthen farmer owned institutions and support national policies that are favourable to the growth of such institutions. Fundamental to NDDB's efforts are cooperative strategies and principles.

- NDDB’s efforts transformed India’s rural economy by making dairying a viable and profitable economic activity for millions of milk producers while addressing the country’s need for self-sufficiency in milk production.

- NDDB has been reaching out to dairy farmers by implementing other income generating innovative activities and offering them sustainable livelihood.

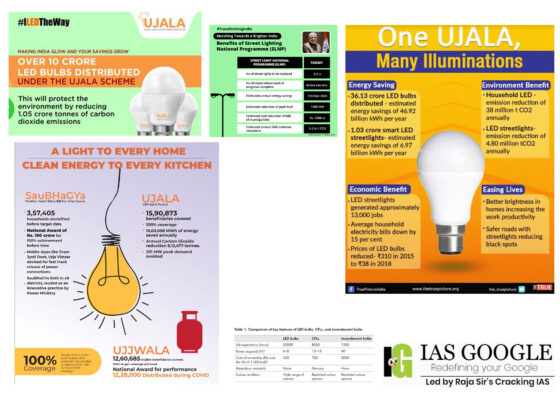

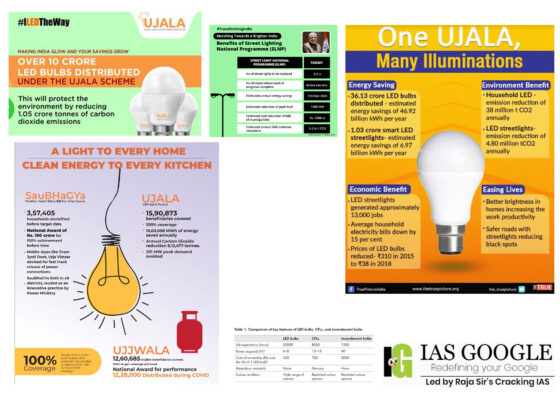

- Till date, EESL has installed over 1.23 crore (as on 16.03.2022) LED street lights in ULBs and Gram Panchayats across India under SLNP Scheme.

About Unnat Jyoti by Affordable Light Emitting Diode (LED) for All (UJALA)

About Unnat Jyoti by Affordable Light Emitting Diode (LED) for All (UJALA)

- UJALA [Unnat Jyoti by Affordable Light Emitting Diode (LED) for All] was launched on 5th January, 2015 to provide energy efficient LED bulbs to domestic consumers at an affordable price.

- The programme was successful in bringing down the retail price of the LED bulbs from Rs. 300- 350 per LED bulb in the year 2014 to Rs 70-80 per bulb, in a short span of 3 years.

- To set up a phase-by-phase LED distribution system across the country.

- The goal is to raise public awareness about the necessity of energy efficiency.

- To promote energy efficiency at the household level throughout India.

- To convey the notion that energy efficiency has a long-term influence on environmental preservation.

- The government’s goal under the scheme is to replace all 77 crore inefficient bulbs in the country with LED bulbs.

- The replacement will result in a 20,000 MW load reduction and an 80 million tonnes decrease in Green House Gas emissions each year.

- Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL) is responsible for the implementation of the scheme. The EESL is a joint venture of four state-run electricity firms under the Ministry of Power.

- These electricity firms are NTPC, PFC, REC, and Power Grid Corporation. State governments are voluntarily adopting the Ujala scheme.

- The Ujala scheme is currently active in 26 states and 6 union territories as of November 18, 2016. Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, and Manipur are the three states that have yet to embrace the plan.

- Increase the demand of LED lights by aggregating requirements across the country and provide economies of scale to manufacturers through regular bulk procurement, which helped the manufacturers to reduce the cost of LED bulbs not only for UJALA program but for retail segment as well.

- Promote the use of the most efficient lighting technology at affordable rates to domestic consumers which benefits them by way of reduced energy bill while at the same time improving their quality of life through better illumination.

- Enhance consumer awareness of the financial and environmental benefits of using energy efficient appliances, thus creating a market for energy efficient appliances.

- On May 1, 2015, the Unnat Jyoti by Affordable LEDs for All UJALA scheme was established to promote energy efficiency at the domestic level and raise consumer knowledge about utilizing efficient equipment to cut electricity bills and benefit the environment.

- The program encourages people to utilize LED bulbs instead of incandescent, tube, and CFL bulbs.

- LED bulbs are given at subsidized rates under the UJALA scheme through specific counters only put up at designated locations throughout the country.

- A beneficiary is any household with a metered power connection from the relevant Electricity DISCOM. When making an upfront payment, the applicant just needs to show government-issued identification such as an Aadhar card, Voter ID, or Passport. Furthermore, while making an EMI payment, you must submit a copy of the most recent power bill.

- UJALA LED bulbs are 9W and cost between Rs. 75 and Rs. 95 per bulb. The modest differences between states are due to differences in relevant taxes, delivery expenses, and so on.

- You can purchase the LED bulb either in full or in monthly or bi-monthly instalments on the electricity bill. In Gujarat, for example, users can pay Rs. 70 per bulb upfront or opt for an EMI option.

- With the EMI option, you will pay Rs. 75 in total and Rs. 20 will be added to their bi-monthly power payment for four-bill cycles.

- UJALA LED bulbs are available for purchase at DISCOM offices, Electricity bill cash counters, specific EESL kiosks, and weekly ‘haat’ markets. Under Ujala Scheme, a consumer may purchase a maximum of 10 bulbs.

- An incandescent bulb has a lifespan of about 1,200 hours, whereas LEDs have a substantially longer lifespan, ranging from 50,000 to 1,00,000 hours.

- In comparison to incandescent lights, LEDs use about 75% less energy.

- Because LEDs convert energy into light, they run at a much lower temperature than super-heated incandescent light bulbs. Incandescent bulbs, on the other hand, turn heat into light.

- Industry data and consumer surveys indicate that LED bulbs are mainly replacing CFLs. Going ahead, the programme needs to focus on lower income households and small commercial establishments who buy incandescent bulbs to phase out their use. One way to do this is to re-emphasise the on-bill financing mechanism.

- EESL cannot expect to continue selling LED bulbs perpetually and replace the vast network of dealers and retailers across India. Half of the demand for LED bulbs in India is still generated through the UJALA programme.

- A sudden withdrawal may result in a sharp drop in demand with a possible rise in price. A gradual withdrawal combined with shifted focus to low-income households can be a good exit strategy.

- Household surveys reveal that buyers are not keen on exchanging the faulty LED bulbs under warranty because they are either unaware of the option or have difficulty with the exchange process.

- EESL can make it convenient for consumers to return the faulty bulbs by conducting periodic collection drives or collaborating with local retail shops.

- UJALA prices for LED bulbs are half of the market price. Our kiosk surveys in Pune have revealed that distribution vendors can take advantage of this by charging a premium, while still keeping the final price below the market price.

- Consumers unaware of the latest prices still buy them and vendors pocket the premium. EESL and the local DISCOM can conduct awareness campaigns to avoid this.

- A stricter monitoring of the distribution of UJALA bulbs is required to ensure that they do not end up in retail shops. Also, data should be collected on participating households to facilitate systematic evaluation of the actual savings realised either through bill analysis or randomised consumer surveys.

- Periodic evaluation of the savings and processes should be conducted to increase their effectiveness.

- People are mostly replacing CFLs with LEDs under the UJALA programme. CFLs, with their mercury content, pose serious problems if they are discarded without care. EESL can collaborate with an e-waste company to set up collection kiosks for old CFLs along with the LED kiosks.

- Buyers should not be mandated to submit CFLs but could use the facility if they want to discard their used CFLs. This can ensure their proper disposal.

- The dramatic price drop in LED bulbs was a result of a global price reduction and the significant potential of economies of scale. The large-scale uptake was also possible as LED bulbs are relatively cheaper than other appliances, as well as easy to buy and store.

- Although the bulk procurement model has the potential of transforming the market, programmes for other appliances should not be burdened with expectations of a speed and scale similar to that of the UJALA programme.

- A gradual and predictable increase in demand for energy efficient technology is better for the creation of a market and its supporting eco-system such as testing laboratories and standards.

- A gradual transformation also prevents a mass lock-in to a particular technology given the rapid pace of technology change. Also, a proper withdrawal plan must be in place so that the market is not disturbed when the programme is withdrawn.

- The EESL limited the role of DISCOMs in the programme to ensure faster and higher levels of participation. However, DISCOMs should not completely withdraw from the Demand Side Management (DSM) programmes.

- Effective DSM programmes can significantly impact the demand and load profiles which in turn can impact planning for the purchase of power by DISCOMs. They should actively engage with EESL to design specific programmes according to their needs.

- EESL and BEE should continue their efforts to build the capacity of DISCOMs with regard to DSM programmes.

- A comprehensive evaluation of the varied impacts of the programme and the effectiveness of the processes is crucial. The BEE can commission these studies at the national level while regulatory commissions or DISCOMs can commission evaluation studies at the local level.

- A realistic estimate of achieved savings can reliably inform the planning process and also increase the credibility of the programmes.

- A programme design document delineating all the features and processes along with their rationale can be useful as a reference for all the stakeholders, a guide for future programmes, and a tool to hold all the actors accountable.

- Similarly, during the course of the programme, reports on testing, evaluation, and warranty claims should be made public on a regular basis. This will help identify any major issues during the implementation and also increase the public credibility of the programme.

- To conclude, UJALA has succeeded in creating a large and sustainable market for LED bulbs in India using the no-subsidy, bulk procurement model. Demand for LED bulbs has increased manifold and the retail market price (for the LED bulbs sold beyond UJALA) has dropped by a third.

- Domestic manufacture of LED bulbs has increased, efficiency standards are being implemented, and the number of accredited testing laboratories has grown, all pointing to sustainability of the LED lighting market. It has also created a significant awareness about LED bulbs in India, further contributing to their increasing demand.

- Going ahead, EESL should target low-income households and small commercial establishments who are still buying incandescent bulbs. It can conduct special campaigns and also focus more on the on-bill financing mechanism that reduces the upfront cost of the LED bulbs. The streamlined procurement processes and innovative marketing campaigns from the UJALA model can be used for other appliances as well.

- However, stricter monitoring and evaluation should be incorporated in the programme design to ensure the quality of the appliances, compliance of various processes, proper disposal of old appliances, and realistic calculation of achieved savings. Although the bulk procurement model does not involve subsidy, it is important to quantify the savings realistically to factor them into planning optimised capacity addition and adequate climate change mitigation actions.

- Street Lighting National Program (SLNP) was launched on 5th January 2015 as “Prakash Path” – National Program for adoption of LED Street Lighting. The main objective was to convert conventional Street Lights with energy efficient LED Street Lights.

- Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL) was designated as the implementing agency to implement this program across Pan- India. This initiative was a part of the Government’s efforts to spread the message of energy efficiency in the country and bring market transformation for energy efficient appliances.

- EESL joined hands with the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs), Municipal Bodies, Gram Panchayats (GPs) and Central & State Governments to implement SLNP across India.

- Under SLNP, 1576 Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) have been enrolled, out of these ULBs, work has been completed in 1060 ULBs.

- EESL is also implementing LED Street lighting projects in Gram Panchayats on the same service model as the SLNP for municipalities with the objective to promote the use of efficient lighting in rural areas. So far, EESL has installed 26 lakh LED street lights in rural areas of Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Goa and Telangana.

- The LED Street lights are installed after a detailed survey of the existing infrastructure is undertaken. The survey inter-alia looks at the infrastructure gaps, verification of inventory and mapping locations for setting up CCMS (Centralized Control and Monitoring System)

- Mitigate climate change by implementing energy efficient LED based street lighting

- Reduce energy consumption in lighting which helps DISCOMs to manage peak demand

- Provide a sustainable service model that obviates the need for upfront capital investment as well as additional revenue expenditure to pay for procurement of LED lights

- Enhance municipal services at no upfront capital cost of municipalities

- EESL replaces the conventional street lights with LEDs at its own costs and consequent reduction in energy and maintenance cost of the municipality is used to repay EESL over a period of time.

- The contracts that EESL enters into with Municipalities are typically of 7 years duration where it not only guarantees a minimum energy saving but also provides free replacements and maintenance of lights at no additional costs to the municipalities.

- The service model enables the municipalities to go in for the state-of-the-art street light with no upfront capital cost and repayments to EESL are within the present level of expenditure.

- Thus, there is no additional revenue expenditure required to be incurred by the municipality for change over to smart and energy efficient LED street lights.

- Reduce energy consumption in lighting which helps DISCOMs to manage peak demand. Market Transformation by reduced pricing through demand aggregation and shifting the buying preference from Sodium Vapour/Fluorescent Lighting to LED Based Solid-State Lighting.

- Under this model, ESCO replaces the conventional street lights with LEDs at its own costs (without any need for municipalities to invest) and the consequent reduction in energy and maintenance cost of the municipality is used to repay ESCO over a period of time.

- Mitigate climate change by implementing energy efficient LED based street lights resulting in reduced GHG emissions. Also, reduction in energy intensity thereby supporting India’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) goals.

- Improvement in the safety & security in public area in rural, semi urban, and urban settings through better illumination.

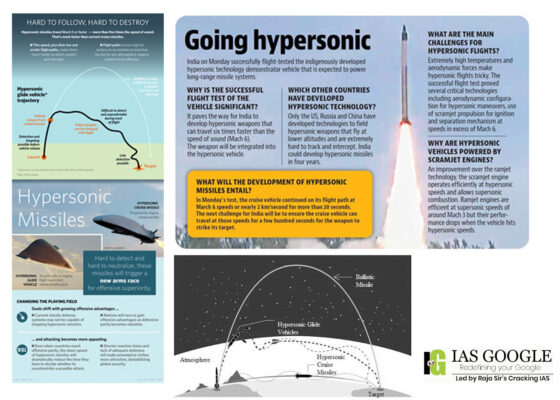

What is a Hypersonic Missile?

What is a Hypersonic Missile?

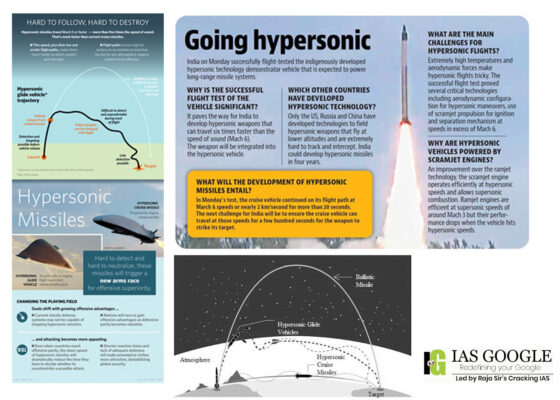

- A hypersonic missile is a weapon system which flies at least at the speed of Mach 5 i.e., five times the speed of sound and is manoeuverable.

- The manoeuvrability of the hypersonic missile is what sets it apart from a ballistic missile as the latter follows a set course or a ballistic trajectory. Thus, unlike ballistic missiles, hypersonic missiles do not follow a ballistic trajectory and can be maneuvered to the intended target.

- The two types of hypersonic weapons systems are Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGV) and Hypersonic Cruise Missiles.

-

- Hypersonic Cruise Missile

-

-

- This type of missile reaches its target with the help of a high-speed jet engine that allows it to travel at extreme speeds, in excess of Mach-5.

- It is non-ballistic – the opposite of traditional Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) which utilises gravitational forces to reach its target.

-

-

- Hypersonic Glide Vehicle

-

-

- This type of hypersonic missile utilises re-entry vehicles. Initially, the missile is launched into space on an arching trajectory, where the warheads are released and fall towards the atmosphere at hypersonic speeds.

- Rather than leaving the payload at the mercy of gravitational forces – as is the case for traditional ICBMs – the warheads are attached to a glide vehicle which re-enters the atmosphere, and through its aerodynamic shape it can ride the shockwaves generated by its own lift as it breaches the speed of sound, giving it enough speed to overcome existing missile defence systems.

- The glide vehicle surfs on the atmosphere between 40-100km in altitude and reaches its destination by leveraging aerodynamic forces.

-

- The HGV are launched from a rocket before gliding to the intended target while the hypersonic cruise missile is powered by air breathing high speed engines or ‘scramjets’ after acquiring their target.

- Hypersonic missiles travel at more than five times the speed of sound in the upper atmosphere — or about 6,200km per hour.

- This is slower than an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) but the shape of a hypersonic glide vehicle allows it to manoeuvere toward a target or away from defences.

- Hypersonic missiles can also travel for longer without being detected by radar.

- Combining a glide vehicle with a missile that can launch it partially into orbit — a so-called fractional orbital bombardment system (FOBS) — could thus strip adversaries of reaction time and traditional defence mechanisms.

- ICBMs, by contrast, are long-range missiles that carry nuclear warheads on ballistic trajectories that leave the earth's atmosphere before re-entry, pursuing a parabolic trajectory towards its target – but they never reach space.

- Both the US and USSR studied FOBS during the Cold War, and the USSR deployed such a system starting in the 1970s. It was removed from service by the mid-80s.

- Submarine-launched ballistic missiles had many of the advantages of FOBS — reducing detection times and making it impossible to know where a strike would come from — and were seen as less destabilizing than FOBS.

- Hypersonic weapons can enable responsive, long range strike options against distant, defended or time critical threats (such as road mobile missiles) when other forces are unavailable, denied access or not preferred.

- Conventional hypersonic weapons use only kinetic energy i.e., energy derived from motion, to destroy unhardened targets or even underground facilities.

- Hypersonic missiles offer a number of advantages over subsonic and supersonic weapons, particularly with regard to the prosecution of time-critical targets (for example, mobile ballistic missile launchers), where the additional speed of a hypersonic weapon is valuable.

- It can also overcome the defences of heavily-defended targets (such as an aircraft carrier).

- The development and deployment of hypersonic weapon systems will provide states with significantly enhanced strike capabilities and potentially, the means to coerce.

- This will be particularly the case where a major regional power, such as Russia, may seek to coerce a neighbour, leveraging the threat of hypersonic strikes against critical targets. As such, the proliferation of hypersonic capabilities to regional states could also be destabilising, upsetting local balances of power. However, it could also strengthen deterrence.

- Hypersonic weapons may also be problematic in terms of escalation control in the context of a NATO-Russia or US-China confrontation. This concerns dual-capable systems, that is, systems with both conventional and nuclear capabilities, for example, the Kinzhal.

- The dual-capable systems raise the issue of discrimination. In the context of hypersonic threats, this is compounded by the reduced time available to decision-makers to respond to an incoming threat.

- Moreover, the development of submarine-launched hypersonic missiles would raise the potential threat – real or perceived – of attempted decapitation strikes, utilising the combination of the inherent stealth of a nuclear-powered submarine and the speed of a hypersonic missile.

- Subsonic missiles are slower than the speed of sound. Most well-known missiles fall into this category, such as the US Tomahawk cruise missile, the French Exocet, and the Indian Nirbhay. Subsonic missiles travel at a speed around Mach-0.9 (705 mph).

- Subsonic missiles are slow and easier to intercept, but they still play a huge role in modern battlefields. Not only are they substantially cheaper to produce as the technological challenges have already been overcome and mastered, but subsonic missiles provide an additional layer of strategic value due to its low speed and small size.

- Once a subsonic missile has been launched, it can loiter in proximity to its intended target, as a result of its fuel efficiency. This, combined with its comparatively low speed, gives senior military decision-makers ample time to decide if a strike should be continued or abandoned.

- Comparatively, a hypersonic or supersonic missile compresses the time afforded to senior decisions makers into a matter of minutes.

- A supersonic missile exceeds the speed of sound (Mach 1) but is not faster than Mach-3. Most supersonic missiles travel at a speed between Mach-2 and Mach-3, which is up to 2,300 mph.

- The most well-known supersonic missile is the Indian/Russian BrahMos, is currently the fastest operational supersonic missile capable of speeds around 2,100–2,300 mph.

- A hypersonic missile exceeds Mach-5 (3,800 mph) and is five times faster than the speed of sound. Currently, there is no operational defence system that can deny the use of these strategic weapons.

- As a result, many world powers including the US, Russia, India, and China are working on hypersonic missiles. However, there are many technological hurdles to overcome, particularly with regards to sustaining combustion inside the missile system, while enduring extreme temperatures of hypersonic speed.

- Hypersonic weapons could challenge detection and defence due to their speed, manoeuvrability and low altitude of flight.

- The ground-based radars or terrestrial radars cannot detect hypersonic missiles until late in the flight of the weapon. This delayed detection makes it difficult for the responders to the missile attack to assess their options and to attempt to intercept the missile.

- The United State of America’s current command and control model for missile defence would be incapable of processing data quickly enough to respond to and neutralize an incoming hypersonic missile.

- Apart from Russia, which announced its hypersonic missile ‘Kinzhal’ or Dagger in 2018 and has now used it for the first time in battle conditions in Ukraine, China too is reportedly in possession of this weapon system and has twice used it to circumnavigate the globe before landing near a target in August 2021.

- The Russian Kinzhal missile is said to be a modification of its Iskander missile and was test fired from a MiG-31 aircraft in July 2018 striking at a target 500 miles away.

- As per Russian media reports the Kinzhal has a top speed of Mach 10 with a range up to 1200 miles when launched from a MiG-31. Russia is also said to be using the missile on Su-34 long range fighter and is working towards mounting it on Tu-22M3 strategic bomber.

- China is said to have tested a HGV in August 2021 launched by a Long March rocket. There are reports that China may use this weapon system by mating conventionally armed HGVs with the DF-21 and DF-26 missiles that it possesses.

- China has also extensively tested the DF-ZF HGV with a range of 1200 miles and is said to have fielded it in 2020. According to US defence officials quoted in the Congressional report, China has also successfully tested Starry Sky-2 (Xing Kong-2), a nuclear capable hypersonic vehicle prototype in August 2018.

- In the US, the hypersonic weapons are being developed under its Navy’s conventional Prompt Strike Programme as well as through Army, Air Force and Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

- While the US, Russia and China are in advanced stages of hypersonic missile programmes, India, France, Germany, Japan and Australia too are developing hypersonic weapons.

- The recent tests are the moves in a dangerous arms race in which smaller Asian nations are striving to develop advanced long-range missiles, alongside major military powers.

- Hypersonic weapons, and FOBS, could be a concern as they can potentially evade missile shields and early warning systems.

- China already has ~100 nuclear-armed ICBMs that can strike the US.

- India is also developing an indigenous, dual capable (conventional as well as nuclear) hypersonic cruise missile as part of its Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle programme and has successfully tested a Mach 6 scramjet in June 2019 and September 2020.

- India operates approximately 12 hypersonic wind tunnels and is capable of testing speeds up to Mach 13.

- India has been working on this for a few years, and is just behind the US, Russia and China. DRDO successfully tested a Hypersonic Technology Demonstrated Vehicle (HSTDV) in September 2020, and demonstrated its hypersonic air-breathing scramjet technology.

- According to sources, India has developed its own cryogenic engine and demonstrated it in a 23-second flight. India will try to make a hypersonic cruise missile, using HSTDV.

- Sources said only Russia has proven its hypersonic missile capability so far, while China has demonstrated its HGV capacity. India is expected to be able to have a hypersonic weapons system within four years, with medium- to long-range capabilities.

- While China is ahead of India, a “lot of things about China are psychological”.

- According to a Pentagon report in 2020, China may have either achieved parity, or even exceeded the US in land-based conventional ballistic and cruise missile capabilities.

- China’s missile development is “definitely a concern for us, but we will definitely evolve”. If China strikes a strategic target of India, “we will hit back with equal potential, and hit them at the place where it matters the most.”

- China has given Pakistan the technology, “but getting a technology and really using it, and thereafter evolving and adopting a policy is totally different”.

- Hypersonic missiles are called “weapons of deterrence” but will not be used. They “will continue to deter, but unlikely that China will ever use this. But if it does, India will not sit idle.”

- On nuclear capability, although India does not call BrahMos nuclear, it can be used. India’s only nuclear missiles are Prithvi and Agni, but beyond those, tactical nuclear weapons can be fired from some IAF fighter jets or from Army guns, which have a low range, around 50 km.

- Hypersonic missiles are so valuable because there is currently no operational or reliable method of intercepting them. However, as defence technology progresses countermeasures will emerge. Technologies such as directed energy weapons, particle beams and other non-kinetic weapons will be likely candidates for an effective defence against hypersonic missiles.

- Hypersonic weapons reduce the time required to prosecute a target (especially compared to current subsonic cruise missiles), the warning time available to an adversary, and the time available for defensive systems to engage the incoming threat.

- Although hypersonic threats would pose a significant challenge to current surface-to-air and air-to-air missile systems, such systems would, particularly in the conventional precision strike role, require a robust intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance (ISTAR) network.

- Targeting the supporting network kinetically and through means such as cyber and electronic attacks could significantly degrade the operational effectiveness of long-range hypersonic weapons.

- In addition, counterforce operations targeting the launch platforms ‘left-of-launch’ can be undertaken, although, this may not be possible in the case of long-range systems such as the Kinzhal and Avangard.

- In the mid-to-long term, directed energy weapons and electromagnetic rail guns, as well as enhanced performance missile interceptors, could provide defence against hypersonic threats.

- The USN is already close to outfitting its ships with a 150-kilowatt laser that will be able to target missiles, drones and other modern threats.

- Another countermeasure has been proposed by the Missile Defense Agency. A network of space-based satellites and sensors would theoretically be able to track hypersonic glide vehicles globally. This would be a huge first step in hypersonic missile defence.

- In addition, Lockheed Martin was awarded a $2.9 bn contract to develop Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared Satellites. There is a high chance that these satellites will aim to fill the hole that exists for early supersonic/hypersonic detection.

- This is all future technology though. At the moment, the race for operational hypersonic missiles is closely contested between the US, Russia, and China.

- After all, there is still no effective defence against a barrage of conventional ICBMs.

- After a long hiatus, hypersonic missile research and development is back in full swing. Major Powers, such as Russia, China and the US have been racing to develop hypersonic missile – a missile system so fast that it cannot be intercepted by any current missile defence system.

- Hypersonic missiles will play a huge role in foreign policy in the years to come, as core pillars of geopolitics such as geography and technological power can be undermined by hypersonic missiles. And, given a recent uptick in “successful” tests from the likes of China and Russia, hypersonic missiles are much closer than we think, forcing a global re-assessment of traditional notions of deterrence.

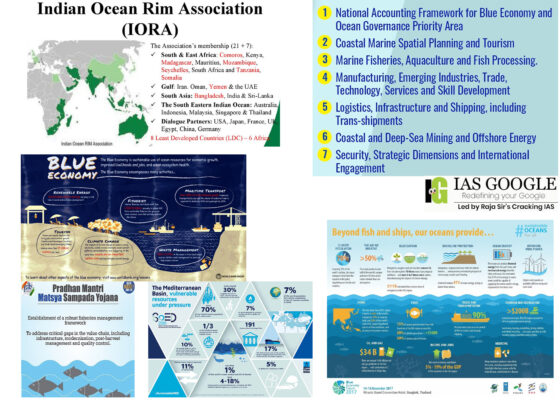

About Blue Economy

About Blue Economy

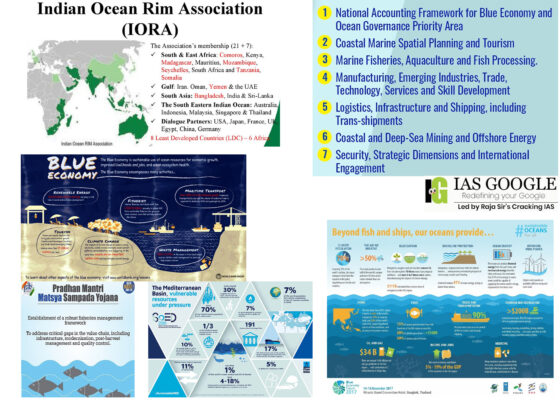

- Blue economy essentially refers to the multitude of ocean resources available in the country that can be harnessed to aid the production of goods and services because of its linkages with economic growth, environmental sustainability, and national security.

- The blue economy is a vast socio-economic opportunity for coastal nations like India to utilise ocean resources for societal benefit responsibly.

- India’s blue economy is a subset of the national economy comprising the entire ocean resources system and human-made economic infrastructure in marine, maritime, and onshore coastal zones within the country’s legal jurisdiction.

- With some 7,500 kilometers, India has a unique maritime position. Nine of its 29 states are coastal, and its geography includes 1,382 islands.

- There are nearly 199 ports, including 12 major ports that handle approximately 1,400 million tons of cargo each year.

- Besides, India’s Exclusive Economic Zone of over 2 million square kilometers has a bounty of living and non-living resources with significant recoverable resources such as crude oil and natural gas. Also, the coastal economy sustains over 4 million fisherfolk and coastal communities.

- Given India’s vast maritime interests, the blue economy occupies a vital potential position in India’s economic growth.

- It could well be the next force multiplier of GDP and well-being, provided sustainability and socio-economic welfare are centred.

- Therefore, India's draft blue economy policy is envisaged as a crucial framework towards unlocking the country’s potential for economic growth and welfare.

- The MoES prepared the draft blue economy policy framework in line with the Government of India’s Vision of New India by 2030.

- According to the draft policy, the blue economy is one of the ten core dimensions for national growth. It dwells on policies across several key sectors to achieve the holistic development of India’s economy.

- The draft document focuses on seven thematic areas such as

-

- national accounting framework for the blue economy and ocean governance;

- coastal marine spatial planning and tourism;

- marine fisheries, aquaculture, and fish processing;

- manufacturing, emerging industries, trade, technology, services, and skill development;

- logistics, infrastructure and shipping including transhipment;

- coastal and deep-sea mining and offshore energy;

- security, strategic dimensions, and international engagement.

- India has tapped its vast coastline to build ports and other shipping assets to facilitate trade, but the entire spectrum of its ocean resources is yet to be fully harnessed. Several countries have undertaken initiatives to utilise their blue economy.

- For instance, Australia, Brazil, the United Kingdom, the United States, Russia, and Norway have developed dedicated national ocean policies with measurable outcomes and budgetary provisions.

- Canada and Australia have enacted legislation and established institutions at federal and state levels to ensure progress and monitoring of their blue economy targets.

- With a draft blue economy policy framework of its own, India is now all set to harness the vast potential of its ocean resources.

- Fisheries, which is a vital oceanic resource forms the core of the Blue Economy, as one of the main resources of the Indian Ocean which provide food to hundreds of millions of people and greatly contribute to the livelihoods of coastal communities.

- It plays an important role in ensuring food security, poverty alleviation and also has a huge potential for business opportunities.

- There has been a strong increase in fish production from 861,000 tons in 1950 to 11.5 million tons in 2010 and the world's total demand for fish and fisheries products is expected to rise from 50 million to 183 million tons in 2015, with aquaculture activities predicted to cover about 73% of this increase.

- Aquaculture, which offers huge potential for the provision of food and livelihoods, will under the Blue Economy incorporate the value of the natural capital in its development, respecting ecological parameters throughout the cycle of production, creating sustainable, decent employment and offer high value commodities for export.

- To meet the increasing public demand for seafood products, natural fisheries resources are being over-exploited and threatened. Therefore, the urgent need to find a balance between population need and environmental health has provided impetus to the promotion of sustainable fishing and aquaculture.

- Well-managed fisheries can deliver billions more in value and millions of tonnes more fish each year, while aquaculture has the potential for continued strong growth to supply the food requirements of a growing world.

- The world population is expected to increase to an estimated 9 billion people in 2050, which is 1.5 times greater than the current population, resulting in an increase in countries' demands on fossil fuels.

- Recently there has been a collapse in the price of crude oil, but the possibility of an eventual normalization (of return to higher prices) should not be disregarded and thus necessitates the continued attention of IORA Member States to consider alternative renewable sources of energy.

- Renewable sources of energy such as solar and wind are already being implemented worldwide. However, additional incentives in renewable energy are strongly in demand to further decrease the burden on fossil fuels.

- The time is therefore appropriate to explore the potential of renewable energy derived from the ocean. The ocean offers vast potential for renewable "blue energy" from wind, wave, tidal, thermal and biomass sources.

- In line with the above efforts, it is also proposed to bring together the offshore oil and gas community with the renewable ocean energy community to undertake a gap analysis in relation to Oil and Gas exploration.

- In this regard the potential for the development of the offshore oil and gas industry in the Indian Ocean region should also be taken into consideration.

- The seaport and maritime transport sector are one of the important priority sectors under the Blue Economy, in which Member States are showing a greater interest.

- In spite of the continuous rise of maritime transport and shipping transactions in the region, uneven distribution of trade exists among the rim countries, where only a handful are benefiting economically from maritime exchanges and transportation.

- Some Member States unfortunately are struggling to keep pace with the rapid development and complexity of maritime trade as they face challenges in terms of congestion, new information technology and equipment, improvement of port infrastructure and professional services.

- In this regard, regional cooperation is important for unlocking the bottlenecks to ports development and maritime economy expansion in the Indian Ocean so as to enhance blue growth through economic cooperation and trade relations between Member States.

- With the decreasing inland mineral deposits and increasing industrial demands, much attention is being focused on mineral exploration and mining of the seabed.

- The seabed contains minerals that represent a rapidly developing opportunity for economic development in both the Exclusive Economic Zones of coastal nations and beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

- Seabed exploration in the Indian Ocean has already started, but the major constraints in the commercialization of these resources lie in the fact that Member States have limited data on the resources their exclusive economic zone (EEZ) possesses, lack capacity for exploration, mining and processing of these minerals. Therefore, improved information is needed to assess the potential across the region.

- Marine biotechnology (or Blue Biotechnology) is considered an area of great interest and potential due to the contribution to the building of an eco-sustainable and highly efficient society.

- A fundamental aspect is related to aquaculture, whereby new methodologies will help in: selective breeding of species; increasing sustainability of production; and enhancing animal welfare, including adjustments in food supply, preventive therapeutic measures, and use of zero-waste recirculation systems.

- Aquaculture products will also be improved to gain optimal nutritional properties for human health. Another strategic area of marine biotechnology is related to the development of renewable energy products and processes, for example through the use of marine algae.

- In addition, the marine environment is a largely untapped source of novel compounds that could be potentially used as novel drugs, health, nutraceuticals and personal care products; Blue Biotechnology could be further involved in addressing key environmental issues, such as in bio-sensing technologies to allow in situ marine monitoring, in bioremediation and in developing cost-effective and non-toxic antifouling technologies.

- Finally, marine derived molecules could be of high utility as industrial products or could be used in industrial processes as new enzymes, biopolymers, and biomaterials

- Marine tourism, with its related marine activities (including cruise tourism), is a growing industry that represents an important contributor to the economy of countries and for generating employment.

- However, these activities, if not managed sustainably, could develop a parasitic relationship with the environment, leading to destruction and degradation of marine habitats and environment, loss of biodiversity, marine pollution and over-exploitation of resources.

- This necessitates actions for environmental protection in order to prevent any irreversible impacts (for example sedimentation over coral organisms by sheer human physical impact, beach erosion, and mangrove clearance) that may arise from marine tourism industry.

- Protecting local marine resources is one of the most urgent needs in promoting sustainable tourism. Sustainable coastal tourism can assist with the preservation of artisanal fishing communities, allow for subsistence fishing, protect the environment, and make positive contributions to sustainable economic development.

- In view of addressing these issues, there is a need to:

-

- create more and increase the size of marine protected areas (MPAs);

- establish and promote sustainable marine tourism; create opportunities for financing MPAs;

- develop more marine parks, among others.

- In addition to providing areas for recreation and enjoyment, marine parks support billions of dollars of vital ecosystem services worldwide.

- The Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana. (PMMSY) is designed to address critical gaps in fish production and productivity, quality, technology, post-harvest infrastructure and management, modernisation and strengthening of value chain, traceability, establishing a robust fisheries management framework and fishers? welfare.

- The PMMSY is an umbrella scheme with two separate Components namely (a) Central Sector Scheme (CS) and (b) Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS).

- The Centrally Sponsored Scheme (CSS) Component is further segregated into non-beneficiary oriented and beneficiary orientated subcomponents/activities under the following three broad heads:

-

- Enhancement of Production and Productivity

- Infrastructure and Post-harvest Management

- Fisheries Management and Regulatory Framework

- Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada has been approved at a total estimated investment of Rs. 20,050 crores comprising of Central share of Rs. 9407 crores, State share of Rs 4880 crores and Beneficiaries contribution of Rs. 5763 crores.

- PMMSY will be implemented in all the States and Union Territories for a period of 5 (five) years from FY 2020-21 to FY 2024-25.

- A scheme to bring about Blue Revolution through sustainable and responsible development of fisheries sector in India with highest ever investment of Rs.20,050 Crores in the fisheries sector, for implementation over a period of five years from financial year 2020-21 to financial year 2024-25 in all States/Union Territories.

- The PMMSY inter-alia provides financial support for acquisition technologically advanced fishing vessels, deep sea fishing vessels for traditional fishermen, fishing boats and nets for traditional fishermen, providing safety kits for fishermen of traditional and motorized fishing vessels, communication and/or tracking devices for traditional and motorized vessels and infrastructure facilities for Monitoring, Control and Surveillance, etc.

- The Government of India, in 2018-19, has also extended the facility of Kisan Credit Card (KCC) to fisheries and animal husbandry farmers to help them and to meet their working capital needs.

- The Fisheries and Aquaculture Infrastructure Development Fund (FIDF) has been created at a total outlay of Rs. 7522 Crores to provide concessional finance to Eligible Entities (EEs). Besides, the concerned coastal State Governments/UTs are also providing tax rebate for fuel and other subsidies to Indian fishermen.

- Major Impact, Including Employment Generation Potential

-

- The fish production is likely to be enhanced from 13.75 million metric tons (2018-19) to 22 million metric tons by 2024-25.

- A sustained average annual growth of about 9% in fish production is expected.

- An increase in the contribution of GVA of fisheries sector to the Agriculture GVA from 7.28% in 2018-19 to about 9% by 2024-25.

- Double export earnings from the present Rs.46,589 crores (2018-19) to about Rs.1,00,000 crores by 2024-25.

- Enhancement of productivity in aquaculture from the present national average of 3 tons to about 5 tons per hectare.

- Reduction of post-harvest losses from the reported 20-25% to about 10%.

- Doubling of incomes of fishers and fish farmers.

- Generation of about 15 lakhs direct gainful employment opportunities and thrice the number as indirect employment opportunities along the supply and value chain.

- Enhancement of the domestic fish consumption from about 5 kg to about 12 kg per capita.

- Encouragement of private investment and facilitation of growth of entrepreneurship in the fisheries sector.

- Fisheries is an important sector in India. It provides employment for millions of people and contributes to the food security of the country.

- With a coastline of over 8,000 km, an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of over 2 million sq km, and with extensive freshwater resources, fisheries play a vital role.

- The gross value addition of the fisheries and aquaculture sector during 2016-17 was Rs. 1,33,492 Crores which is about 0.96% of the National Gross Value Added (GVA) and 5.37% to the agricultural GVA (2016-17).

- During the year 2017-18, the country exported 13,77,244 tonnes fish and fisheries worth Rs. 45106.89 crore (7.08 billion US $).

- Presently India is the second largest fish producing and second largest aquaculture nation in the world after China. The total fish production during 2017-18 (provisional) is registered at 12.61 million metric tonnes (MMT) with a contribution of 8.92 MMT from inland sector and 3.69 MMT from marine sector.

- The marine fishery potential in the Indian waters have been estimated at 5.31 MMT constituting about 43.3% demersal, 49.5% pelagic and 4.3% oceanic groups.

- Marine Fisheries contributes to food security and provides direct employment to over 1.5 mn fisher people besides others indirectly dependent on the sector. There are 3,432 marine fishing villages and 1,537 notified fish landing centres in 9 maritime states and 2 union territories.

- According to the CMFRI Census 2010, the total marine fisherfolk population was about 4 million comprising 864,550 families. Nearly 61% of the fishermen families were under BPL category.

- The average family size was 4.63 and the overall sex ratio was 928 females per 1000 males. The Indian coastline can be delineated into 22 zones, based on the ecosystem structure and functions.

- The Indian boat type ranges from the traditional catamarans, masula boats, plank-built boats, dugout canoes, machwas, dhonis to the present-day motorized fibre-glass boats, mechanized trawlers and gillnetters.

- In the marine fisheries sector, there were 194,490 crafts in the fishery out of which 37% were mechanized, 37% were motorized and 26% were non-motorized.

- Out of a total of 167,957 crafts fully owned by fisherfolk 53% were non-motorized, 24% were motorized and 23% were mechanized. Among the mechanized crafts fully owned by fishermen, 29% were trawlers, 43% were gillnetters and 19% were Dol netters.

- Threat of sea borne terror – piracy and armed robbery, maritime terrorism, illicit trade in crude oil, arms, drug and human trafficking and smuggling of contraband etc.

- Natural Disasters – every year tsunamis, cyclones, hurricanes typhoons etc leave thousands of people stranded and property worth millions destroyed.

- Man-Made problems – Oil spills, climate change continue to risk the stability of the maritime domain.

- Impact of climate change – changes in sea temperature, acidity, threaten marine life, habitats, eutrophication, creation of Dead Zones and the communities that depend on them.

- Marine pollution – in the form of excess nutrients from untreated sewage, agricultural runoff, and marine debris such as plastics

- Overexploitation of marine resources – illegal, unreported, and unregulated extraction of marine resources.

- The United Nations Member States, including India, adopted 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, in 2015 as a universal call to take action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030. SDG 14 seeks to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.

- Several countries have undertaken initiatives to harness their blue economy. For instance, Australia, Brazil, United Kingdom, United States, Russia, and Norway have developed dedicated national ocean policies with measurable outcomes and budgetary provisions.

- Canada and Australia have enacted legislation and established hierarchal institutions at federal and state levels to ensure progress and monitoring of their blue economy targets.

- The IORA Indian Ocean Blue Carbon Hub aims to build knowledge and capacity relevant to protecting and restoring blue carbon ecosystems (which include mangroves, seagrasses and tidal marshes) throughout the Indian Ocean in a way that enhances livelihoods, reduces risks from natural disasters and helps mitigate climate change.

- Blue carbon ecosystems have an immense capacity to sequester carbon, a feature which makes them a good candidate for efforts to mitigate climate change. Indeed, the name reflects the high amount of organic carbon they contain. In addition, they support livelihoods in a variety of ways including through fisheries, and can reduce the effects of storms.

- The Indian Ocean contains a disproportionate amount of the world’s blue carbon ecosystems, and the nations of the Indian Ocean have an opportunity to lead the world in harnessing the benefits that they provide. The Hub seeks to support IORA Member States to do this through evidence-based actions.

- The objectives of the Hub include:

-

- Providing a source of advice to, and expertise for, IORA Member States

- Engaging in and facilitating research that seeks to improve knowledge and provide evidence base for development of robust policy and finance mechanisms

- Establishing best practice and disseminating information about best practice

- Developing partnerships with organisations that can assist with implementation of activities that meet these objectives.

- Priority activities for the Hub include a think-tank series, a visiting fellowship program for early career professionals, and scientific expeditions. The think-tank series aims to convene leading thinkers, innovators and practitioners to address some of the most fundamental challenges preventing implementation of evidence-based policy. The first of these was held in Mauritius in February 2020, and focussed on finance.

- The Hub was announced by Australia’s Foreign Minister at the Third IORA Ministerial Blue Economy Conference, in Dhaka in September 2019. It is based at the Indian Ocean Marine Research Centre in Perth, Australia.

- Seychelles became the first country in the world to launch sovereign Blue Bonds.

- It is a debt instrument issued by governments, development banks etc to raise capital from investors to finance marine and ocean-based projects.

- It will help in expansion of marine protected areas, improved governance of priority fisheries and the development of the Seychelles’ blue economy.

- The blue bond is inspired by the green bond concept.

- Deep Ocean Mission: It was launched with an intention to develop technologies to harness the living and non-living resources from the deep-oceans.

- India-Norway Task Force on Blue Economy for Sustainable Development: It was inaugurated jointly by both the countries in 2020 to develop and follow up joint initiatives between the two countries.

- Sagarmala Project: The Sagarmala project is the strategic initiative for port-led development through the extensive use of IT enabled services for modernization of ports.

- O-SMART: India has an umbrella scheme by the name of O-SMART which aims at regulated use of oceans, marine resources for sustainable development.

- Integrated Coastal Zone Management: It focuses on conservation of coastal and marine resources, and improving livelihood opportunities for coastal communities etc.

- National Fisheries Policy: India has a National Fisheries policy for promoting 'Blue Growth Initiative' which focuses on sustainable utilization of fisheries wealth from marine and other aquatic resources.

- The number and type of educational programmes on both the traditional and emerging sectors of blue economy should be offered at universities and engineering/technical institutes for sustained supply of trainer personnel.

- The number of vocational training sectors and on-the-job training should be regularly conducted both in universities and Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) to help disseminate knowledge at the local level

- The level of awareness of the number of employment opportunities in the blue economy and the future prospects needs to be increased both at the central and state level. This can be done by conducting frequent sessions with the target audience at both the school and university levels.

- The government should support in providing the required infrastructure for skill development in the blue economy sectors. This can be done financially by supporting the initiatives and programmes that focus on expanding human resources for the sectors of the blue economy.

- The world is looking towards oceans for a number of new emerging sectors and opportunities, but the success of these new sectors, in addition to traditional marine employment, would solely depend on oceans' health and long-term sustainability of their fragile ecosystems for which it is important to boost blue economy and deduce the right plan of action to create the right balance between economy and environment.

- The Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), formerly known as the Indian Ocean Rim Initiative and the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation (IOR-ARC), is an international organisation consisting of 23 states bordering the Indian Ocean.

- The IORA is a regional forum, tripartite in nature, bringing together representatives of Government, Business and Academia, for promoting co-operation and closer interaction among them.

- It is based on the principles of Open Regionalism for strengthening Economic Cooperation particularly on Trade Facilitation and Investment, Promotion as well as Social Development of the region.

- The Coordinating Secretariat of IORA is located at Ebene, Mauritius.

- The organisation was first established as Indian Ocean Rim Initiative in Mauritius on March 1995 and formally launched on 6–7 March 1997 by the conclusion of a multilateral treaty known as the Charter of the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Co-operation.

- The idea is said to have taken root during a visit of former South African Foreign Minister, Pik Botha, to India in November 1993. It was cemented during the subsequent presidential visit of Nelson Mandela to India in January 1995.

- Consequently, an Indian Ocean Rim Initiative was formed by South Africa and India. Mauritius and Australia were subsequently brought in. In March 1997, the IOR-ARC was formally launched, with seven additional countries as members: Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Yemen, Tanzania, Madagascar and Mozambique.

- The apex body of the IOR-ARC is the Council of (Foreign) Ministers (COM). The meeting of the COM is preceded by the meetings of the Indian Ocean Rim Academic Group (IORAG), Indian Ocean Rim Business Forum (IORBF), Working Group on Trade and Investment (WGTI), and the Committee of Senior Officials (CSO).

- To promote sustainable growth and balanced development of the region and member states

- To focus on those areas of economic cooperation which provide maximum opportunities for development, shared interest and mutual benefits

- To promote liberalisation, remove impediments and lower barriers towards a freer and enhanced flow of goods, services, investment, and technology within the Indian Ocean rim.

- Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) has identified six priority areas, namely:

-

- maritime security,

- trade and investment facilitation,

- fisheries management,

- disaster risk reduction,

- academic and scientific cooperation and

- tourism promotion and cultural exchanges.

- In addition to these, two focus areas are also identified by IORA, namely Blue Economy and Women's Economic Empowerment.

- IORA members undertake projects for economic co-operation relating to trade facilitation and liberalisation, promotion of foreign investment, scientific and technological exchanges, tourism, movement of natural persons and service providers on a non-discriminatory basis; and the development of infrastructure and human resources, poverty alleviation, promotion of maritime transport and related matters, cooperation in the fields of fisheries trade, research and management, aquaculture, education and training, energy, IT, health, protection of the environment, agriculture, disaster management.

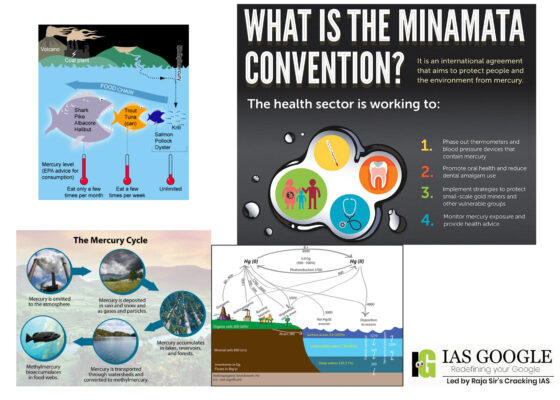

Findings of Minamata Convention (COP-4)

Findings of Minamata Convention (COP-4)

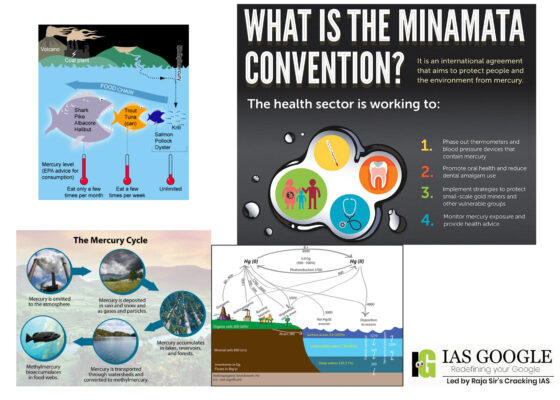

- The issue of Mercury Pollution is being discussed at the second round of the fourth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention on Mercury (COP-4.2). The meeting is being held in-person from March 21-25 in Bali, with online participation.

- The non-binding declaration calls upon parties to:

-

- Develop practical tools and notification and information-sharing systems for monitoring and managing trade in mercury

- Exchange experiences and practices relating to combating illegal trade in mercury, including reducing the use of mercury in artisanal and small-scale gold mining

- Share examples of national legislation and data and information related to such trade

- The declaration has undergone two out of three written consulting stages and is widely expected to be adopted at the conclusion of the summit.