- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

India’s Fertility Rate declines, Women More Conscious Than Men

In a milestone of sorts, India’s National Family Health Survey 2019-21 (NFHS-5) has recorded a decline in the total fertility rate (the average children a woman has) from 2.2 in the previous survey ( 2015-16) to 2.0 in the latest one. And here too, it was 1.6 in an urban population and 2.1 in a rural setting. Public health experts are taking a moment to let this sink in, as it indicates the population is stabilising – some states are inching up, others largely trending downwards, the direction is towards equilibrium.

The dip in fertility is attributed to a combination of factors, including better contraception initiatives and government health and family welfare schemes. But a key factor is the education of the girl child and efforts to improve overall health and nutrition.

With about 25 million babies born every year, health administrators have often pointed out that no Government anywhere in the world would be capable of creating schools and other facilities at such a pace. A stabilisation was what the health administration has been working towards all these years, and indeed, that moment has arrived, it seems.

There are too many variables to make that prediction, including how China handles its declining population. Across geographies, there is a declining trend, but experts believe that India may still be on the path to becoming the most populous nation. A critical step, however, has been achieved in stabilising growth. India has achieved replacement level fertility (pegged at 2.1), defined as the level at which the decline on a sustained basis would result in a generation replacing itself.

The short answer is no. The latest NFHS is the fifth in the series and was done in two phases because of pandemic-induced restrictions and lockdowns. It provides information on population, health, and nutrition across India, down to the state and union territories. But different regions reflect different stages of development.

The second phase of the NFHS (covering 14 States and UTs) saw a TFR range from 1.4 in Chandigarh to 2.4 in Uttar Pradesh. All Phase-II States have achieved replacement level of fertility (2.1) except Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh.

According to reports, five states with TFR above 2 were Bihar, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Manipur. Just shy of TFR 2 were Haryana, Assam, Gujarat, Uttarakhand and Mizoram at 1.9. Six states - Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Arunachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha were at 1.8. Further at 1.7 were Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Nagaland, and Tripura. And TFR was the lowest in this survey in West Bengal, at 1.6.

Public health voices and doctors say the government should focus on more of the same – educating the girl child across the board. It’s one of the single most critical factors, as with education, the family’s overall well-being improves, say specialists in women and child health.

Alongside, family planning and reproductive health awareness need to be imparted to adults, and they need to be encouraged to adopt these measures. Coercive policies should be kept out. Education gives young people, especially girls, a greater sense of awareness and well-being that prevents early marriages and pregnancies. This is critical in keeping the population in check, even as health administrators would now brainstorm on calibrating this growth from now on, to prevent the demographic profile from losing its balance between young and older populations.

Here’s a closer look at what has shaped this demographic milestone for India:

1. Urban-rural gap

Rural areas have always had far greater fertility rates than urban areas. But that gap seems to be closing, with even rural India finally reaching the replacement-level mark (2.1) for the first time in the 2019-21 NFHS. Urban India had reached the mark in the 2005-06 survey.

The gap between the fertility rates in the two geographies was 1 point in 1992-93 (3.7 for rural vs 2.7 for urban), which has narrowed down to 0.5 in the last 30 years.

From a fertility rate of 5.4 in 1971, India’s villages have come a long way. India would not have been able to bring its overall fertility rate in check had rural areas not shown improvement, as a majority of Indians still live in villages.

Not just on the total fertility rate, the countryside has shown improvement on related fertility indicators such as adolescent pregnancies and awareness and practice of family planning as well, the data shows.

2. Fertility age

As women marry later, fertility has been declining across younger age groups, even in the 20-24 and 25-29 brackets when women are at their fertility peak, past data from the Sample Registration System has shown. However, the biggest change was noted in the 15-19 age group, with a marked decline in teenage pregnancies over the years. This should be seen with the fact that fewer women now get married before the legal age of marriage at 18.

The mean age of fertility also inched up from 26.5 years in 2011 to 28.4 years in 2018. The trend of marrying late is more common in cities, and this gets reflected in fertility data, too. The median age of marriage was 19.8 in urban areas compared to 18.1 in rural areas, showed NFHS-4 data. This has been accompanied by a rise in fertility in women above 30 years in cities and towns—the major exception to declining fertility trends.

3. Laggard states

Bihar, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Manipur remain the only five states with fertility rates above the replacement level and the national average. Each of these states has historically been plagued by relatively higher levels of fertility than the rest of India.

Bihar, which suffers from the highest fertility rate, is among the states that have actually seen the biggest declines in fertility since 2015-16. But since it had a fertility rate of 4.0 in 1992-93 compared to the national average of 2.8, in a way it has improved much more than the rest of India in this period.

However, the trend has not really been steady: fertility actually showed an uptick between 1998-99 and 2005-06. Such lack of consistency is somewhat common in each of these five laggard states.

To reach the last mile and attain population stabilization, such states need sustained investments in the education, health and developmental needs of young people, said Sanghamitra Singh, a health scientist at the Population Foundation of India.

4. Underlying roadblocks

India’s declining fertility is not a consequence of any top-down policy or coercive sanctions, but a sign of increasing prosperity. While it still has a long way to go, the country has progressed on a slew of indicators such as literacy, marriage age and family planning, which directly or indirectly impact fertility. In 2018, the fertility rate was 3.0 among women who could not read, compared to 2.1 among literate women.

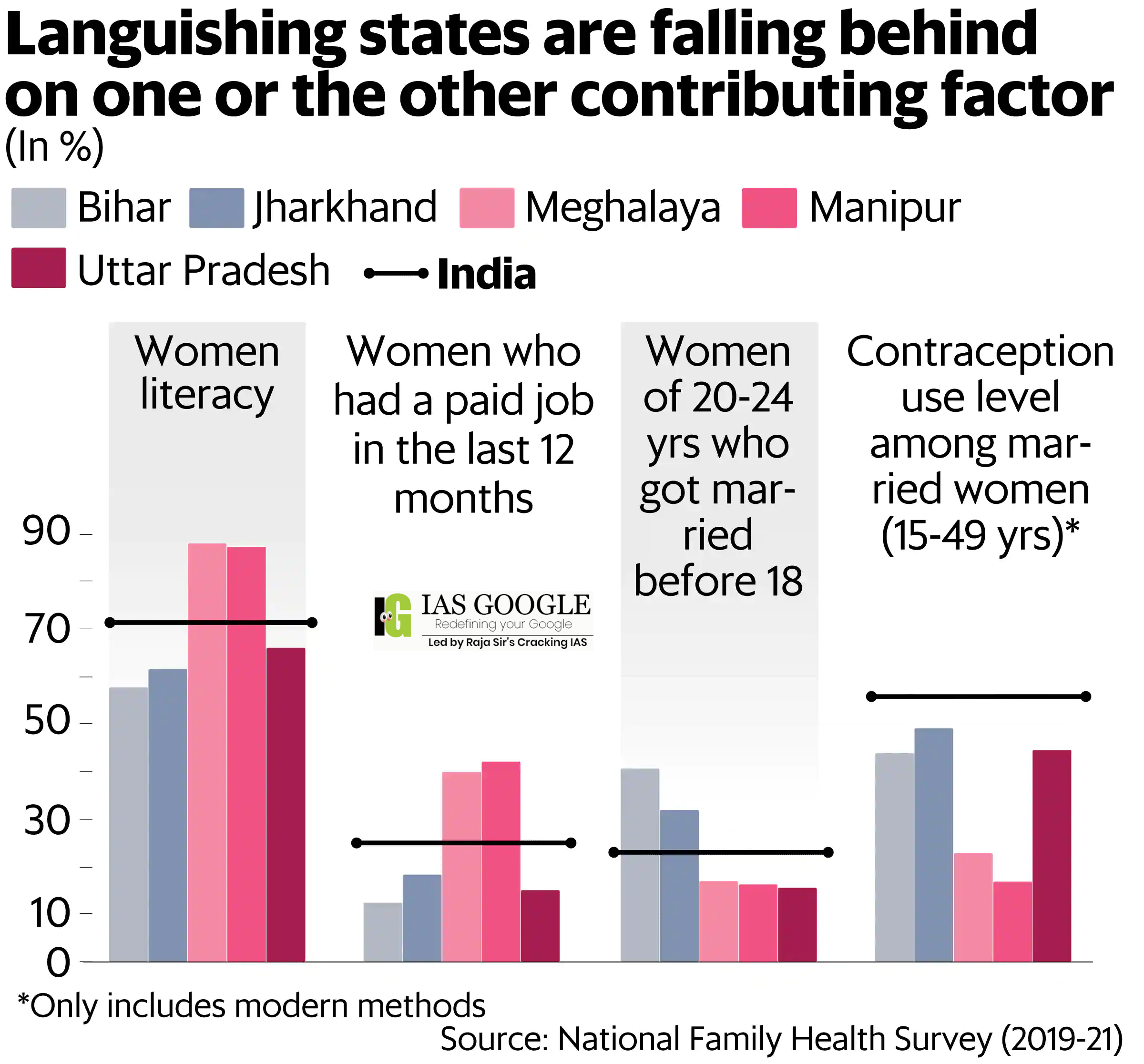

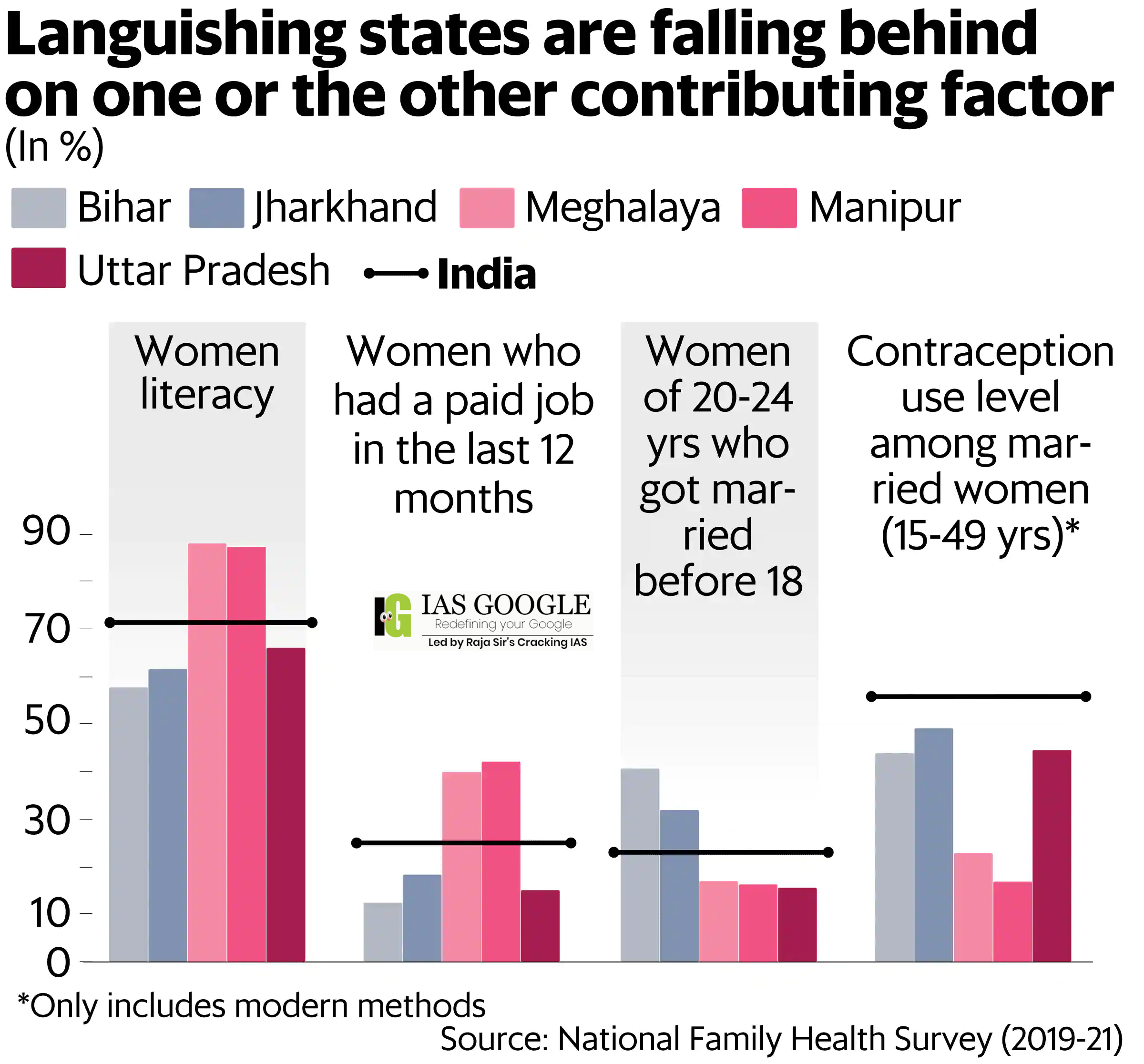

Meghalaya and Manipur performed far better than the national average on the first three indicators, but lagged on the use of contraception.

The five laggard states underperformed on one or the other contributing indicators as well. Bihar and Jharkhand performed worse on women’s literacy, under-age marriage, economic opportunity for women and the practice of family planning methods. Uttar Pradesh fared poorer on three of these four indicators.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies