Last week, the Indian Council of Medical Research (IMCR) released guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, and management for type-1 diabetes. This is the first time the ICMR has issued guidelines specifically for type 1 diabetes, which is rarer than type 2 — only 2% of all hospital cases of diabetes in the country are type 1 — but which is being diagnosed more frequently in recent years.

“Today, more and more children are being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in our country. This may be because the actual prevalence of the disorder is going up in India. It may also reflect better awareness and therefore, improved diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Finally, it could be that children are surviving more due to early diagnosis and better treatment,” the guidelines said.

India is considered the diabetes capital of the world and the pandemic disproportionately affected those living with the disease. Type 1 or childhood diabetes, however, is less talked about, although it can turn fatal without proper insulin therapy.

So, what is type 1 diabetes?

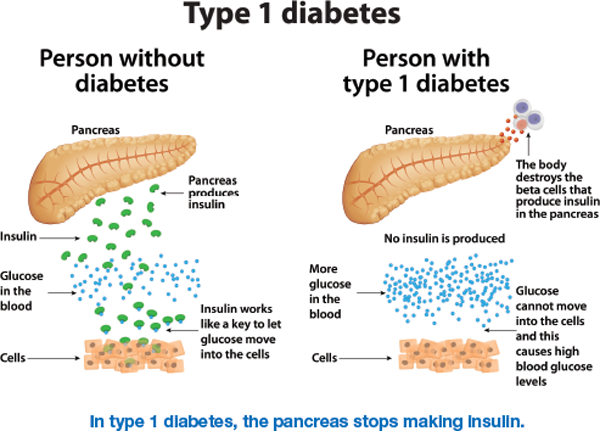

Type 1 diabetes is a condition where the pancreas completely stops producing insulin, the hormone responsible for controlling the level of glucose in blood by increasing or decreasing absorption to the liver, fat, and other cells of the body. This is unlike type 2 diabetes — which accounts for over 90% of all diabetes cases in the country — where the body’s insulin production either goes down or the cells become resistant to the insulin.

“Type 1 diabetes is predominantly diagnosed in children and adolescents. Although the prevalence is less, it is much more severe than type 2. Unlike type 2 diabetes where the body produces some insulin and which can be managed using various pills, if a person with type 1 diabetes stops taking their insulin, they die within weeks. The body produces zero insulin,” said Dr V Mohan, chairman of Dr Mohan’s Diabetes Specialities Centre, and one of the authors of the guidelines.

“Before insulin was discovered 101 years ago, these children would die within months after diagnosis. Now, with better insulin and various innovations, they are living longer. My oldest patient with type 1 diabetes is now 90; he was diagnosed when he was 16,” he said.

Children with the condition usually present to the hospital with severe symptoms of frequent urination, and extreme thirst and nearly a third of them have diabetic ketoacidosis (a serious condition where the body has a high concentration of ketones, a molecule produced when the body isn’t able to absorb glucose for energy and starts breaking down fats instead).

How rare is it?

There are over 10 lakh children and adolescents living with type 1 diabetes in the world, with India accounting for the highest numbers. Of the 2.5 lakh people living with type 1 diabetes in India, 90,000 to 1 lakh are under the age of 14 years. For context, the total number of people in India living with diabetes was 7.7 crore in 2019, according to the Diabetes Atlas of the International Diabetes Federation.

The guidelines, which distinguish type 1 diabetes from other less common forms, also talk about how increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes due to obesity in the younger population can lead to confusion. Among individuals who develop diabetes under the age of 25 years, 25.3% have type 2.

Who is at risk of type 1 diabetes?

The exact cause of type 1 diabetes is unknown, but it is thought to be an auto-immune condition where the body’s immune system destroys the islets cells on the pancreas that produce insulin.

Genetic factors play a role in determining whether a person will get type-1 diabetes. The risk of the disease in a child is 3% when the mother has it, 5% when the father has it, and 8% when a sibling has it.

The presence of certain genes is also strongly associated with the disease. For example, the prevalence of genes called DR3-DQ2 and DR4-DQ8 is 30-40% in patients with type 1 diabetes as compared to 2.4% in the general population, according to the guidelines.

What are the guidelines?

Running into 173 pages, they have been developed by leading diabetologists including Dr Nikhil Tandon, head of the department of endocrinology at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi. “There were several guidelines from international agencies. However, these are the first truly Indian guidelines which look at everything from diagnosis, treatment, and management of type 1 diabetes. It gives detailed guidelines on managing the disease in different conditions such as when one is pregnant or when one is travelling,” said Dr V Mohan.

The guidelines provide details on diet and exercise, insulin monitoring, and prevention and treatment of complications such as retinopathy, kidney disease, and nerve disease. Dr said the guidelines would hopefully act as a ready-reference book for all practicing physicians to improve care for children diagnosed and those living with the condition.

A similar guidebook for type 2 diabetes already exists.

How has treatment of type 1 diabetes evolved over the years?

The discovery of insulin helped children with the condition survive, Dr Mohan said, “but they still have to keep pricking themselves to deliver insulin through their life, Researchers are now looking for a cure and there are some encouraging results from a stem cell therapy to increase islets cells”.

“Every child in the world should get insulin, it is essential medicine. In India, half the people can afford it, and the other half can get it for free at most government hospitals. It costs about Rs 5,000 per month,” he said.

Dr Mohan said continuous glucose monitoring devices and artificial pancreas have started to become available, although these are initial reports and it might take a few years for these to become available as treatments. “Continuous glucose monitoring devices can help monitor the blood glucose levels throughout 24-hour with the help of a sensor. The artificial pancreas go a step further and along with monitoring the levels they can automatically deliver the insulin when needed,” he said.

The guidelines state, “Cost considerations remain an issue in India. Thanks to better management, diabetic ketoacidosis is becoming less common, although in rural areas, and in peripheral centres, it still remains a big problem.”

The guidelines also acknowledge modern glucometers. Urine glucose monitoring (and not blood glucose) was the norm before glucometers. And, initially, even glucometers were expensive, painful, expensive, and not so accurate. “Today, we have blood glucose monitors which are extremely precise and are less painful. Cost of strips, however, still remains a challenge,” the guidelines state.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies