- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Theory of isostasy

Isostasy is a concept in that the lighter crust is floating on top of the denser underlying mantle. It is used to explain how varied topographic heights on the Earth''s surface can occur. Isostatic equilibrium is the ideal state in which the crust and mantle would settle if no disturbing factors existed. Processes that disturb isostasy include the waxing and waning of ice sheets, erosion, sedimentation, and extrusive volcanism. The physical properties of the lithosphere are impacted by how the mantle and crust respond to these perturbations. Understanding the dynamics of isostasy helps us comprehend more complex processes such as mountain development, sedimentary basin formation, continent break-up, and the formation of new ocean basins.

- The theory of isostasy is a fundamental principle that explains the buoyant behavior of the Earth''s lithosphere as it floats upon the more fluid asthenosphere (a part of the upper mantle) below.

- The concept is similar to how objects float in water, with buoyancy being determined by the mass and volume of the displaced fluid.

- The Earth''s crust (or lithosphere) is in gravitational equilibrium and "floats" at a certain elevation depending on its thickness and density.

- Areas of the Earth''s crust that are thicker and more mountainous will extend deeper into the more fluid asthenosphere below.

- Below a certain depth, known as the "compensation depth" or "isostatic depth", the pressure exerted by the overlying rock column is consistent everywhere, regardless of the surface topography.

- When weight is added or removed from the crust, such as through erosion, deposition, or glacial ice accumulation/melting, the crust adjusts either upward or downward in response until equilibrium is reached again. This process is termed isostatic adjustment or isostatic rebound.

|

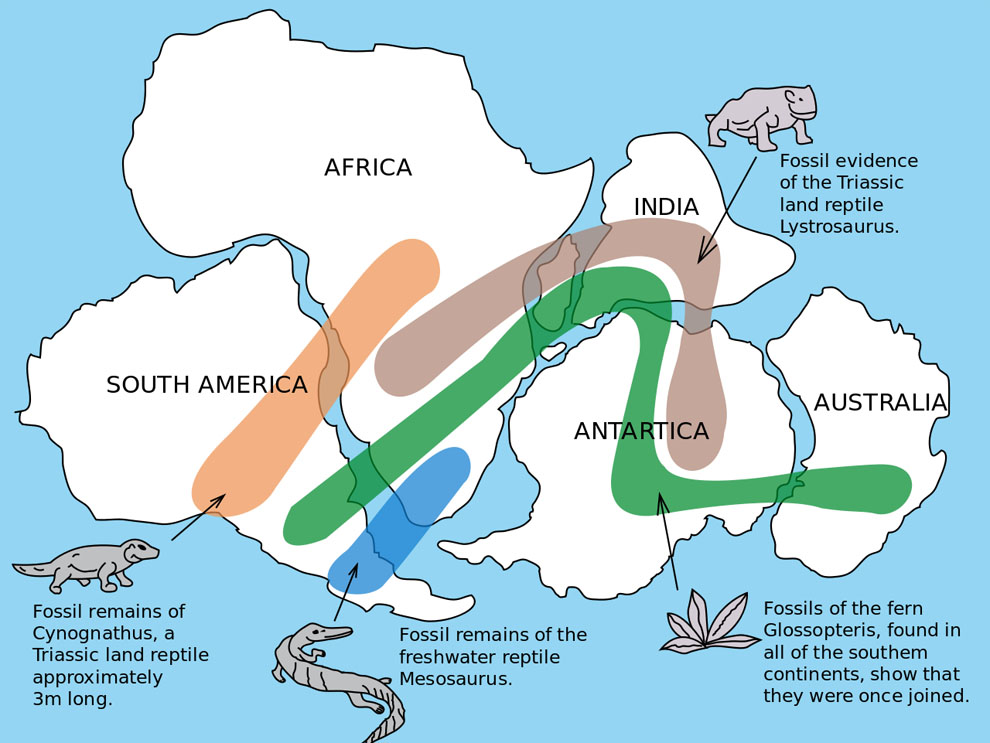

Isostasy and Continental drift The theories of isostasy and continental drift are deeply connected through the broader framework of plate tectonics, which unifies how Earth's surface behaves. Foundation for Plate Tectonics

Crustal Behavior

Support for Plate Movement

Example

|

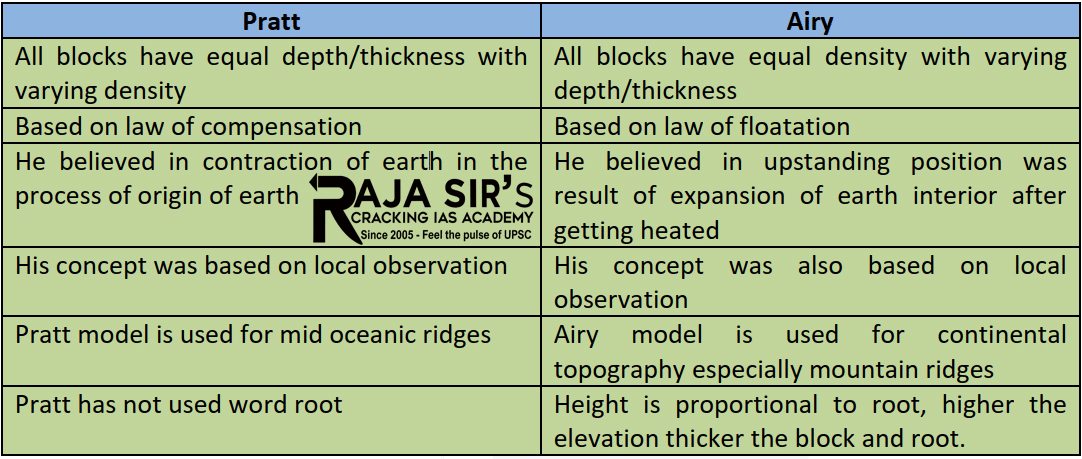

Airy’s View

- The earliest model of isostasy, known as Airy Isostasy, was proposed by George Biddell Airy, a 19th-century British astronomer.

- The lithosphere, the Earth''s outermost shell, is assumed to be a sequence of blocks of constant density in this model.

- While the density of these pieces remains constant, their thickness changes.

- Consider an iceberg drifting in the sea. The "root" of the iceberg lies hidden beneath the water''s surface, while the tip protrudes. The deeper the root spreads beneath the surface, the greater the iceberg''s tip.

- Similarly, mountainous regions of the Earth have a thicker part of the crust (or a "root") stretching down into the denser mantle in Airy Isostasy.

- This extra "root" serves to balance out the mountain''s increased mass above the surface.

- When erosion takes down a mountain''s mass over time, the crust beneath rises in reaction, maintaining isostatic balance.

- Airy Isostasy, in essence, defines a ''floating'' lithosphere in which the thicker sections extend deeper into the mantle, just like larger icebergs sink deeper into the sea.

- This model suggests that the Earth''s crust has varying thickness under mountain ranges compared to ocean basins.

- The thicker portions of the crust (mountains) "float" higher on the asthenosphere, similar to how icebergs with larger submerged parts project more above the water surface.

Pratt’s View

- With his Pratt Isostasy model, British geologist John Henry Pratt took an alternative method to explain isostatic equilibrium.

- Pratt''s hypothesis is based on the density of the lithospheric blocks rather than their thickness.

- Consider a similar-sized wooden block and a sponge floating in a tub of water. Despite being the same size as the wooden block, the sponge will float higher since it is less dense.

- Similarly, in Pratt Isostasy, less dense portions of the Earth''s crust (such as those made of less dense rock types or those underlain by substantial sedimentary deposits) ''float'' higher on the denser mantle than denser ones.

- As a result of these density differences within the crust, Pratt''s model implies that the varied elevations we see across the Earth''s surface, from plains to plateaus, are the result of these density variations within the crust itself.

The concept of isostasy is central to our understanding of various geologic processes and phenomena, including mountain building, sedimentation, erosion, and sea-level changes. It provides insight into the dynamic and responsive nature of the Earth''s crust in relation to the mantle beneath.

The concept of isostasy is central to our understanding of various geologic processes and phenomena, including mountain building, sedimentation, erosion, and sea-level changes. It provides insight into the dynamic and responsive nature of the Earth''s crust in relation to the mantle beneath.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies