- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Drawing the line between personal and non-personal data

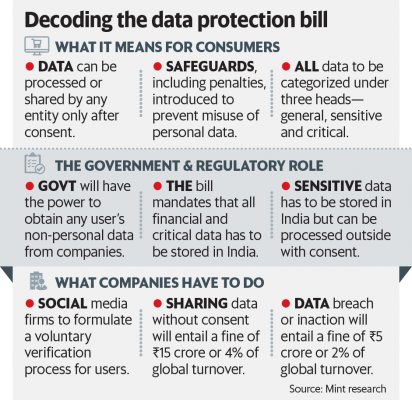

Efforts towards regulating non-personal data are taking place in parallel to deliberations surrounding the regulation of personal data by the Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (PDP Bill).

The PDP Bill defines personal data as data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable.

Accordingly, non-personal data could be of two types. First, data or information which was never about an individual (e.g. weather data). Second, data or information that once was related to an individual (e.g. mobile number) but has now irreversibly ceased to be identifiable due to the removal of certain identifiers through the process of ‘anonymisation’.

In practice, however, the distinction between personal data and non-personal data is fairly murky. The degree to which data is de-identified can lie somewhere in a spectrum between being clearly personal or being clearly anonymous or even somewhere in between.

Efforts towards regulating non-personal data are taking place in parallel to deliberations surrounding the regulation of personal data by the Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (PDP Bill).

The PDP Bill defines personal data as data about or relating to a natural person who is directly or indirectly identifiable.

Accordingly, non-personal data could be of two types. First, data or information which was never about an individual (e.g. weather data). Second, data or information that once was related to an individual (e.g. mobile number) but has now irreversibly ceased to be identifiable due to the removal of certain identifiers through the process of ‘anonymisation’.

In practice, however, the distinction between personal data and non-personal data is fairly murky. The degree to which data is de-identified can lie somewhere in a spectrum between being clearly personal or being clearly anonymous or even somewhere in between.

A government committee headed by Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan has suggested that non-personal data generated in the country be allowed to be harnessed by various domestic companies and entities. The nine-member committee, while releasing the draft report, has kept time till August 13 for the public to send suggestions. It has also suggested setting up of a new authority which would be empowered to monitor the use and mining of such non-personal data.

Non-personal data is any set of data which does not contain personally identifiable information. This in essence means that no individual or living person can be identified by looking at such data. For example, while order details collected by a food delivery service will have the name, age, gender, and other contact information of an individual, it will become non-personal data if the identifiers such as name and contact information are taken out.

The government committee, which submitted its report, has classified non-personal data into three main categories, namely public non-personal data, community non-personal data and private non-personal data. Depending on the source of the data and whether it is anonymised in a way that no individual can be re-identified from the data set, the three categories have been divided.

All the data collected by government and its agencies such as census, data collected by municipal corporations on the total tax receipts in a particular period or any information collected during execution of all publicly funded works has been kept under the umbrella of public non-personal data.

Any data identifiers about a set of people who have the same geographic location, religion, job, or other common social interests will form the community non-personal data. For example, the metadata collected by ride-hailing apps, telecom companies, electricity distribution companies among others have been put under the community non-personal data category by the committee.

Private non-personal data can be defined as those which are produced by individuals which can be derived from application of proprietary software or knowledge.

Unlike personal data, which contains explicit information about a person’s name, age, gender, sexual orientation, biometrics and other genetic details, non-personal data is more likely to be in an anonymised form.

However, in certain categories such as data related to national security or strategic interests such as locations of government laboratories or research facilities, even if provided in anonymised form can be dangerous.

Similarly, even if the data is about the health of a community or a group of communities, though it may be in anonymised form, it can still be dangerous, the committee opined. “Possibilities of such harm are obviously much higher if the original personal data is of a sensitive nature. Therefore, the non-personal data arising from such sensitive personal data may be considered as sensitive non-personal data,” the committee said.

In May 2019, the European Union came out with a regulation framework for the free flow of non-personal data in the European Union, in which it suggested that member states of the union would cooperate with each other when it came to data sharing.

Such data, the EU had then ruled, would be shared by member states without any hindrances, and that they must inform the “commission any draft act which introduces a new data localisation requirement or makes changes to an existing data localisation requirement”.

The regulation, however, had not defined what non-personal data constituted of, and had simply said all data which is not personal would be under the non-personal data category. In several other countries across the world, there are no nationwide data protection laws, whether for personal or non-personal data.

Though the non-personal data draft is a pioneer in identifying the power, role, and usage of anonymised data, there are certain aspects such as community non-personal data, where the draft could have been clearer, experts said.

“Non-personal data often constitutes protected trade secrets and often raises significant privacy concerns. The paper proposes the nebulous concept of community data while failing to adequately provide for community rights,” Udbhav Tiwari, Public Policy Advisor at Mozilla said.

Other experts also believe that the final draft of the non-personal data governance framework must clearly define the roles for all participants, such as the data principal, the data custodian, and data trustees.

A government committee headed by Infosys co-founder Kris Gopalakrishnan has suggested that non-personal data generated in the country be allowed to be harnessed by various domestic companies and entities. The nine-member committee, while releasing the draft report, has kept time till August 13 for the public to send suggestions. It has also suggested setting up of a new authority which would be empowered to monitor the use and mining of such non-personal data.

Non-personal data is any set of data which does not contain personally identifiable information. This in essence means that no individual or living person can be identified by looking at such data. For example, while order details collected by a food delivery service will have the name, age, gender, and other contact information of an individual, it will become non-personal data if the identifiers such as name and contact information are taken out.

The government committee, which submitted its report, has classified non-personal data into three main categories, namely public non-personal data, community non-personal data and private non-personal data. Depending on the source of the data and whether it is anonymised in a way that no individual can be re-identified from the data set, the three categories have been divided.

All the data collected by government and its agencies such as census, data collected by municipal corporations on the total tax receipts in a particular period or any information collected during execution of all publicly funded works has been kept under the umbrella of public non-personal data.

Any data identifiers about a set of people who have the same geographic location, religion, job, or other common social interests will form the community non-personal data. For example, the metadata collected by ride-hailing apps, telecom companies, electricity distribution companies among others have been put under the community non-personal data category by the committee.

Private non-personal data can be defined as those which are produced by individuals which can be derived from application of proprietary software or knowledge.

Unlike personal data, which contains explicit information about a person’s name, age, gender, sexual orientation, biometrics and other genetic details, non-personal data is more likely to be in an anonymised form.

However, in certain categories such as data related to national security or strategic interests such as locations of government laboratories or research facilities, even if provided in anonymised form can be dangerous.

Similarly, even if the data is about the health of a community or a group of communities, though it may be in anonymised form, it can still be dangerous, the committee opined. “Possibilities of such harm are obviously much higher if the original personal data is of a sensitive nature. Therefore, the non-personal data arising from such sensitive personal data may be considered as sensitive non-personal data,” the committee said.

In May 2019, the European Union came out with a regulation framework for the free flow of non-personal data in the European Union, in which it suggested that member states of the union would cooperate with each other when it came to data sharing.

Such data, the EU had then ruled, would be shared by member states without any hindrances, and that they must inform the “commission any draft act which introduces a new data localisation requirement or makes changes to an existing data localisation requirement”.

The regulation, however, had not defined what non-personal data constituted of, and had simply said all data which is not personal would be under the non-personal data category. In several other countries across the world, there are no nationwide data protection laws, whether for personal or non-personal data.

Though the non-personal data draft is a pioneer in identifying the power, role, and usage of anonymised data, there are certain aspects such as community non-personal data, where the draft could have been clearer, experts said.

“Non-personal data often constitutes protected trade secrets and often raises significant privacy concerns. The paper proposes the nebulous concept of community data while failing to adequately provide for community rights,” Udbhav Tiwari, Public Policy Advisor at Mozilla said.

Other experts also believe that the final draft of the non-personal data governance framework must clearly define the roles for all participants, such as the data principal, the data custodian, and data trustees.

|

What is Anonymisation? Anonymisation is currently an unclear standard of de-identification that is to be determined by the Data Protection Authority of India (to be established under the PDP Bill once it is enacted). De-identification is a process by which identifiers that help in attributing data to an individual are removed so that the data is delinked from the individual. The PDP Bill defines anonymisation as the “irreversible process of transforming or converting personal data to a form in which a data principal cannot be identified, which meets the standards of irreversibility specified by the Authority.” Even though the PDP Bill is yet to be enacted, the characterisation of the process as irreversible indicates that the standard must be fairly high. To be clear, there have been studies which show that personal data can never be truly irreversibly anonymised. In order to better understand the process of de-identification, let us consider one of the techniques that have been mentioned in the Gopalakrishnan Committee Report; say K-anonymity. K-anonymity helps in preventing attempts to link the data to a particular person by generalising existing attributes. Let us assume that a digital contact tracing app collects some personal information at the time of registration. This could include identifiers such as name, city, health condition and gender, as represented in table 1 below: Table 1

|

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies