- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Euthanasia In India: An In-Depth Overview

Euthanasia—commonly known as "mercy killing"—refers to intentionally ending a person''s life to relieve suffering. The practice is deeply debated, involving legal, ethical, medical, and social considerations globally and within India. The Indian framework distinctly treats active and passive euthanasia, with the latter being the only form permitted under strict Supreme Court guidelines.

Legal Framework of Euthanasia in India

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life, interpreted to include dignified death.

- Active vs Passive Euthanasia:

- Active euthanasia (deliberate intervention, like administering lethal injection) remains illegal and is treated as homicide under the Indian Penal Code (IPC). Assisting in active euthanasia is also criminalized as abetment to suicide or murder.

- Passive euthanasia (withdrawing or withholding life-support from terminally ill patients) is legally allowed, but only under strict protocols, following Supreme Court judgments.

- Landmark Judgments:

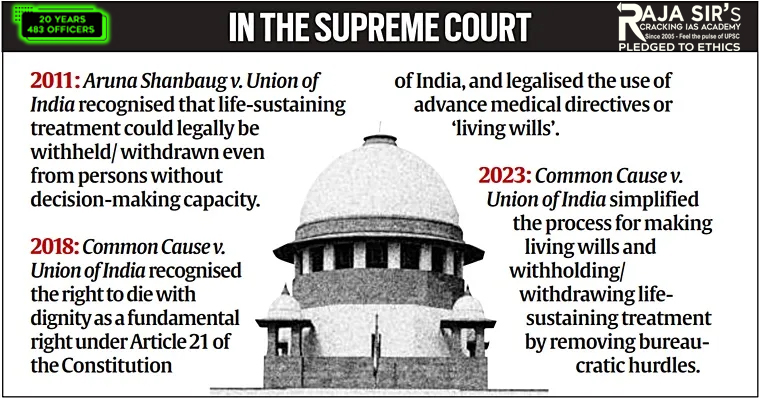

- Aruna Shanbaug v. Union of India (2011): The Supreme Court permitted passive euthanasia, laying guidelines for the withdrawal of life support for terminally ill patients, subject to court oversight and medical board approval.

- Common Cause v. Union of India (2018): The apex court expanded the scope by legalizing passive euthanasia across India and recognizing the validity of "Living Wills"—advance directives allowing individuals to refuse life-sustaining treatment if in a vegetative or terminal state. The ruling tied the right to die with dignity to Article 21 (Right to Life).

- Recent Reforms (2023):

- The Supreme Court further simplified the procedure for passive euthanasia, allowing living wills to be attested by a gazetted officer or notary instead of a magistrate. Living wills can now be integrated into National Health Digital Records for wider accessibility and practical application.

Major Challenges and Ambiguities

Major Challenges and Ambiguities

- Legal Ambiguities: The absence of clear parliamentary legislation on euthanasia (active or passive) leads to confusion, judicial burden, and uneven application. Medical practitioners fear legal repercussions even in cases of passive euthanasia.

- Procedural Complexity: Passive euthanasia requires dual medical board certifications, advance directives, and sometimes judicial approval, making accessibility difficult—especially outside urban centres.

- Societal Attitudes: Surveys show less than 40% public support for euthanasia; religious, cultural, and ethical dilemmas often slow legal and medical adaptation.

Living Wills and Advance Directives

- A "Living Will" allows patients to legally refuse artificial life-support in advance, providing autonomy in end-of-life care. The Supreme Court''s 2018 ruling endorsed living wills, but a robust digital and institutional system is still evolving.

Proposed Reforms and Road Ahead

- Comprehensive Legislation: Need for a clear law by Parliament to detail procedures, safeguards, rights, and responsibilities for passive euthanasia, living wills, and medical boards, protecting practitioners and families.

- Institutional Support: Establish hospital ethics committees and expand hospice and palliative care infrastructure to support dignified end-of-life decisions.

- Public Awareness: Promote informed societal discussion about euthanasia, advance directives, pain management, and patient autonomy.

- Digital Integration: Incorporate living wills into national digital health records, making patient intent accessible to medical boards irrespective of locality.

Ethical and Constitutional Considerations

- The right to die with dignity has been read into Article 21 by the Supreme Court, balancing individual autonomy with state responsibility to protect life and prevent misuse.

- The framework prioritizes checks and balances—medical, legal, and institutional—to guard against coercion and abuse.

India’s approach to euthanasia remains principled and cautious, permitting only passive euthanasia under Supreme Court-mandated guidelines to balance patient autonomy with protection against misuse. While landmark judgments and recent procedural simplifications have advanced the right to die with dignity, major challenges persist due to legal ambiguities, limited access to palliative care, and prevailing social and ethical dilemmas. Moving forward, India must strengthen its framework through comprehensive legislation, digital advances, institutional safeguards, and public awareness, ensuring end-of-life care is both humane and constitutionally consistent.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies