- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Genuinely ‘Federalised Response’ to COVID-19

India is a federal republic, with a parliamentary democracy that operates under the framework of a written Constitution, and whose Courts formally exercise powers of judicial review over legislative and executive action. The response to Covid-19, therefore, involves multiple levels of government, and multiple institutional actors.

India’s success in defeating Covid-19 actively rests upon Centre-State collaboration. However, some recent developments have revealed fissures in Centre-State cooperation. As it is the States which act as first responders to the pandemic, supplying them with adequate funds and autonomy becomes a prerequisite in effectively tackling the crisis. This requires the Centre to view the States as equals, and strengthen their capabilities, instead of increasing their dependence upon itself. In this context, Covid-19 poses a litmus test for the federal structure of India, whose nature is already a matter of debate amongst constitutional experts. Nature of Indian federal structure Federalism traditionally signifies the independence of the Union and State governments of a country, in their respective spheres. However, due to the centralising tendency of Indian federalism, K C Wheare referred to it as “Quasi federal”.Similarly other constitutional experts describe it as, “federation without federalism” and “a Union of Unequal States”, particularly the way it has evolved over the years.

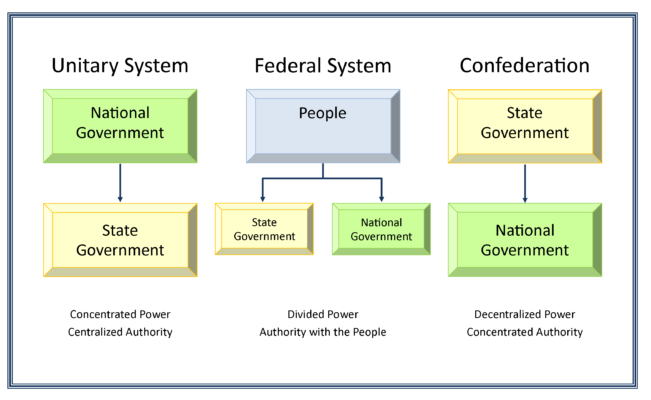

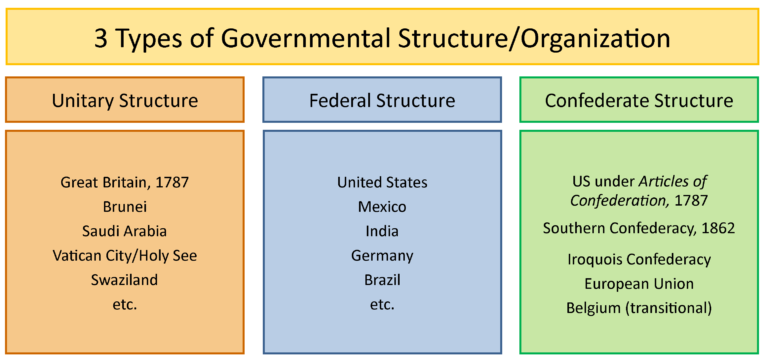

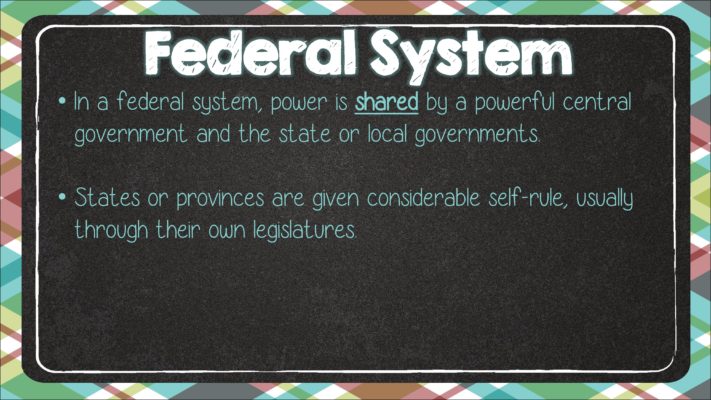

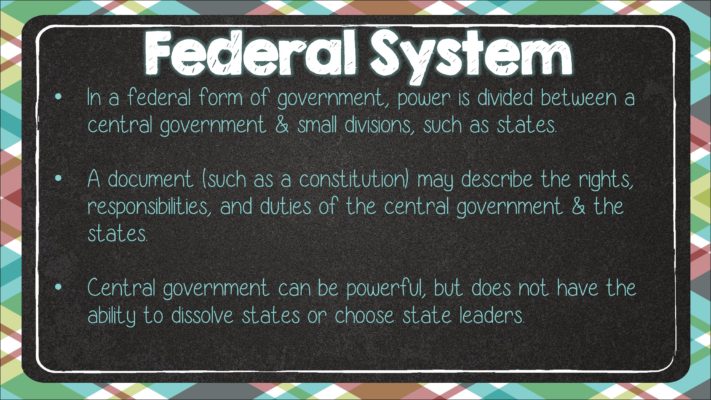

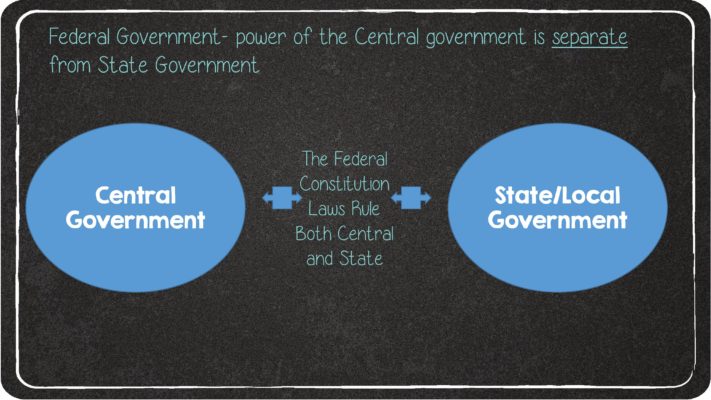

Note:These Info would be useful for General Studies - PAPER 2 - Typologies of Constitution Federal: “Set of Chairs” - A federal form of government splits power between independent states and a central government. The power rests in both places, and each gets its authority from a governing document, like the U.S. Constitution. Independent branches inside the central government may also share power.

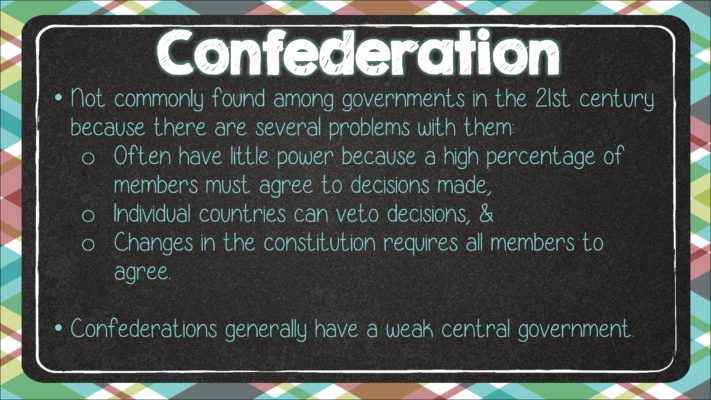

Confederal: “Many Different Chairs” - The confederal form of government is an association of independent states. The central government gets its authority from the independent states. Power rests in each individual state, whose representatives meet to address the needs of the group. America tried a confederal system before writing an entirely new constitution.

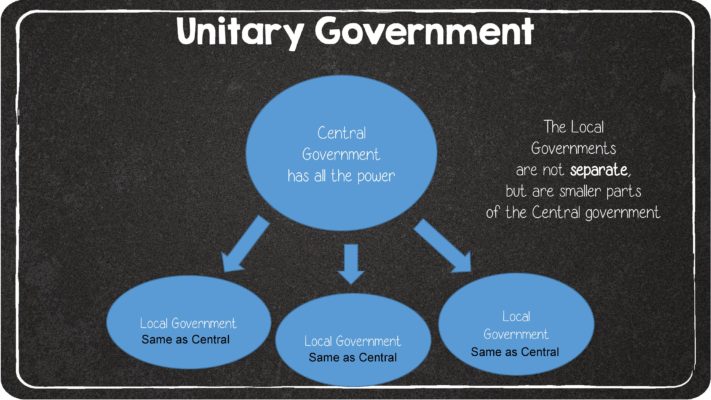

Unitary: “One Big Chair” - In a unitary form of government, all the power rests in a central government. The country may be divided into states or other sub-units, but they have no power of their own. For example, England depends on its Parliament, a legislative body, to create and enforce the laws in the country. The leader of the nation, the Prime Minister, is a member of the Parliament and does not have any more power than its members.

Federal: “Set of Chairs” - A federal form of government splits power between independent states and a central government. The power rests in both places, and each gets its authority from a governing document, like the U.S. Constitution. Independent branches inside the central government may also share power.

Confederal: “Many Different Chairs” - The confederal form of government is an association of independent states. The central government gets its authority from the independent states. Power rests in each individual state, whose representatives meet to address the needs of the group. America tried a confederal system before writing an entirely new constitution.

Unitary: “One Big Chair” - In a unitary form of government, all the power rests in a central government. The country may be divided into states or other sub-units, but they have no power of their own. For example, England depends on its Parliament, a legislative body, to create and enforce the laws in the country. The leader of the nation, the Prime Minister, is a member of the Parliament and does not have any more power than its members.

Features of Indian Federation that reflects a Centralising Tendency

Inequitable Division of Power

Features of Indian Federation that reflects a Centralising Tendency

Inequitable Division of Power

- The division of powers is in favour of the Centre and highly inequitable from that of a true federation.

- The Union List contains more numbers and important subjects (like defence, currency, external affairs, citizenship, railways) than the State List.

- Also, the Centre has overriding authority over the Concurrent List and the residuary powers have also been left with the Centre.

- The Parliament can by unilateral action change the area, boundaries or name of any state (Article 3 of Indian constitution).

- Indian federalism is described as an indestructible union of destructive states.

- The Constitution of India embodies not only the powers of the Centre but also those of the states.

- Further, the bulk of the Constitution can be amended by the unilateral action of the Parliament and the power to initiate an amendment to the Constitution lies only with the Centre.

- During an emergency, the Central government becomes all-powerful and the states go into the total control of the Centre.

- It converts the federal structure into a unitary one without a formal amendment of the Constitution.

- The governor is the head of the state but is appointed by the President. He holds office during the pleasure of the President.

- In this capacity, he/she acts as an agent of the Centre.

- Indian constitution provides for an integrated audit machinery (such as CAG), election commission (such as ECI) and states have no control over these offices.

- Also, features like Single Citizenship, Integrated Judiciary and All India Services also signifies centralising tilt.

| Through a combination of various laws, regulations, guidelines, and orders, a nation-wide lockdown is currently in force to control the spread of the novel coronavirus. Among these, the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (DM Act), was invoked on March 24 to impose a blanket lockdown to ensure “consistency in the application and implementation of various measures across the country”. Accordingly, sweeping guidelines were issued for state governments to follow. However, even before the DM Act was invoked, several State Governments had used their powers under the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897 (ED Act) to deal with the Covid-19 outbreak. Although public order and public health are subjects that lie with the States as per the Indian Constitution, the Centre has used the DM Act to effectively bypass States and assume complete control. This indicates a certain friction in the current legal framework when it comes to managing a crisis such as Covid-19 as the Centre and States do not appear to be fully in sync. States have had to take a backseat in dealing with a public health emergency that, despite having national ramifications, varies from region to region. The fragmented manner in which these legal provisions have been invoked shows a lack of clarity in how the Centre and States have interpreted their roles under the Constitution as it stands. Fragmented legal response • The DM Act empowered the Centre to “take such other measures for the prevention of disaster, or the mitigation, or preparedness and capacity building for dealing with the threatening disaster situation or disaster as it may consider necessary”. • The ED Act enabled States to take necessary actions to prevent the outbreak or spread of dangerous epidemic diseases, whereas it limits the Centre’s role to inspecting ships in ports and detaining persons therein. Interestingly, Municipalities are also empowered by other state laws to take similar measures (for example, Section 479 of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation Act, 1980). • Restrictions have also been imposed under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure by District Magistrates across the country. |

- Due to the Covid-19 induced lockdown, the sources of states’ revenue have collapsed.

- Majority of states’ revenue comes from liquor sales, stamp duty from property transactions and the sales tax on petroleum products.

- However, their expenditure such as on interest payments, social sector schemes and staff salaries remain unchanged.

- Moreover, states are now called upon to spend more on beefing up their health infrastructure and on Covid-19 measures, including testing, treatment and quarantining.

- States’ GST collections have also been severely affected with their dues still not disbursed by the Centre.

- According to the FRBM Act, states cannot borrow from the market over a certain limit.

- Further, the PM-CARES relief fund has been put under the ambit of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) However, contributions to the ‘Chief Minister’s Relief Fund’ or ‘State Relief Fund for Covid-19’ do not qualify as admissible CSR expenditure.

- This directly disincentives donations to any Chief Minister’s Relief Fund; diverts crores in potential State revenues to PM-CARES; and makes the States largely dependent upon the Centre.

- Furthermore, the suspension of MPLADSand diversion of the funds to the Consolidated Fund of Indiamay not be in concurrence of cooperative federalism, as it discourages locally tailored solutions by the MPs.

- In this scenario, states in India have fully become dependent on the Union government for finances.

- For instance, the zone classifications into ‘red’ ,orange’ and ‘green’ have evoked sharp criticisms from several States.

- The States have demanded more autonomy in making such classifications.

- This is despite the fact that state consultation is a legislative mandate cast upon the centre under the Disaster Management Act of 2005 (under which binding COVID-19 guidelines are being issued by the Centre to the States).

- The Disaster Management Act, 2005 envisages the creation of a ‘National Plan’ under Section 11, as well as the issuance of binding guidelines by the Centre to States under Section 6(2), in furtherance of the ‘National Plan’.

- However, section 11(2) of the Act mandates State consultations before formulating a ‘National Plan’.

- The influx of migrant workers into their home states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, which already face severe financial and medical deficits, would worsen matters for the states.

- The sustenance of agricultural, industrial and construction activities would be difficult in the absence of a majority of the workforce in the backdrop of the lifting of restrictions, given these workers are going back to their hometowns.

- In this case, both Centre and states failed to devise a coherent and holistic plan of action to avert the migrant crisis.

- The limit imposed by the FRBM Act must be relaxed so that states who are falling short of funds can borrow money to combat the pandemic and revive the economy.

- These borrowing can be backed by sovereign guarantee by the Union Government.

- The Union government can provide money to states so that they can take necessary action to deal with the crisis at state level.

- The Union government should direct FCI to move the grains from the godowns to states.

- A successful approach to tackle the crisis would still need Centre’s intervention and guidance in a facilitative manner, where the Centre would communicate extensively the best practices across states, address the financial needs effectively, and leverage national expertise for scalable solutions.

- The recent meeting by Indian Prime Minister with the chief ministers of states is a testimony of cooperative federalism. In this context, the government should consider making the Inter-State Council a permanent body.

- Management of disasters and emergencies (both natural and manmade) should be included in the List III (Concurrent List) of the Seventh Schedule.

- An Inter-State Trade and Commerce Commission should be established, which will help realise the idea of ‘One India One Market’.

- Arbitrary control of union over states through the institution of the governor and Article 356, must be checked.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies