- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Mar 16, 2022

INDIA AND THE GLOBAL COMMONS: A CASE STUDY OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOLAR ALLIANCE

India—through ISA, is helping ensure energy security and sustainable livelihoods in sub-Saharan Africa by providing poor communities access to natural, economic, human, and social capital.

Global Commons

Global Commons

Key Findings

Key Findings

Key Statistics Related to Child Marriage

Key Statistics Related to Child Marriage

Provisions of New Drone Policy

Provisions of New Drone Policy

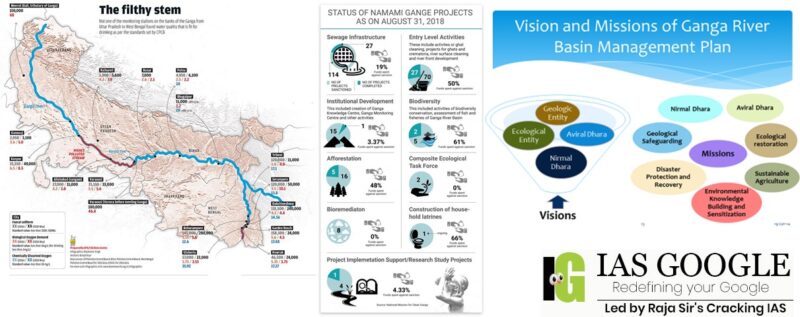

About NMCG

About NMCG

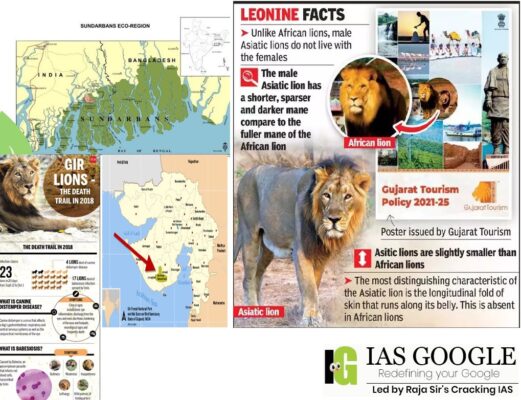

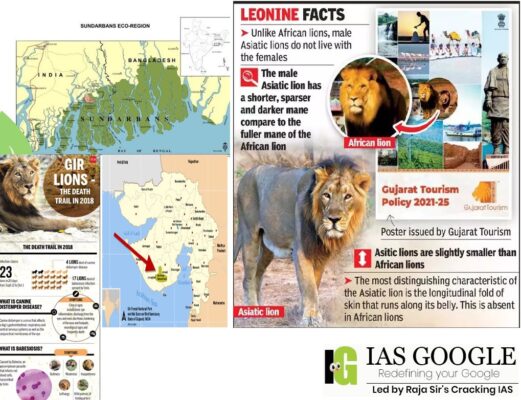

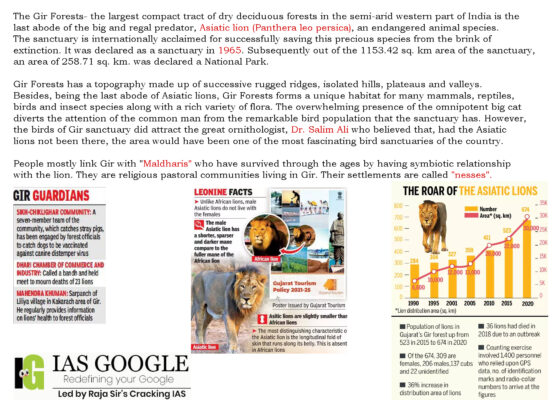

Sunderbans

Sunderbans

Key Findings

Key Findings

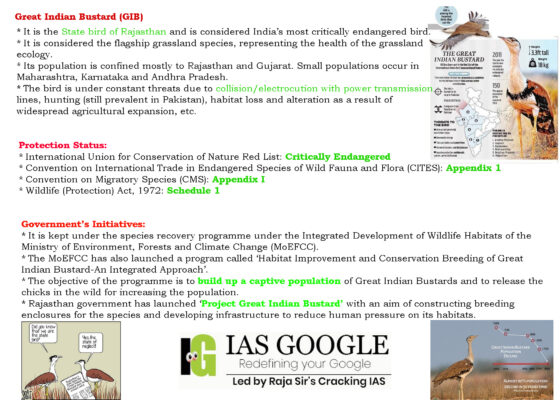

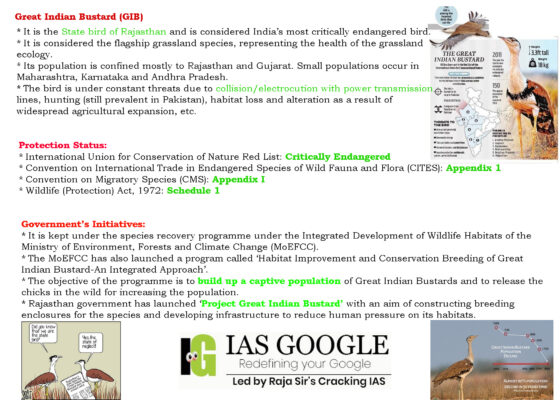

Great Indian Bustards

Great Indian Bustards

Global Commons

Global Commons

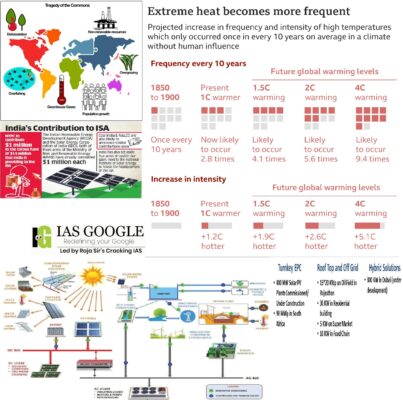

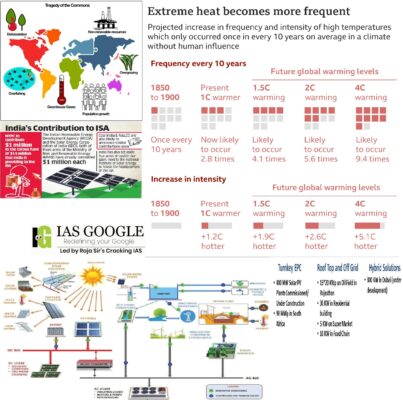

- Climate is a global common. The concept of ‘global commons’ as it relates to climate change means that global policies and actions are needed to address the anthropogenic factors that cause global warming, even if some of these factors could also be tackled effectively at the local level.

- This shared global responsibility underlies the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, which aims to enable states to coordinate their national efforts towards a global common property regime for the atmosphere.

- The agreement primarily aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius relative to pre-industrial levels, and preferably below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

- Limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to mitigate climate change requires transition to a sustainable post-fossil economy by implementing techno-economic, environmental, and energy-efficiency policies, initiatives and programmes.

- The mitigation of global warming, therefore, is a global public good. The international community recognises this and has negotiated various agreements over the years. Three principles underlie these negotiations:

- no country (or continent) can be prevented from enjoying their benefits;

- every country gain from such efforts, regardless of whether it contributes to them; and

- one country’s benefitting from climate mitigation does not affect the benefits available to other countries.

- Over the years, India has played a key role in the North–South politics of climate negotiations. It is a leading member of the Global South, not only because of its vast population and position as an emerging economic power, but also as it has shifted from its earlier defensive, ‘neo-colonial’ attitude on the matter of climate responsibility to a more proactive and internationalist approach in recent climate engagements.

- Even so, overall, in global negotiations, India has held on to its position as a developing country. It has consistently argued for state sovereignty, principles of equity, and common but differentiated responsibilities regarding cuts in GHG emissions.

- International climate negotiations are important forums for India to use diplomatic leverage in pursuing its foreign policy objectives and strengthening its role as a globally responsible actor.

- While its historical GHG emissions and responsibility for climate change may be low, its current and projected emissions are on a steep rise.

- It has chosen a cooperative strategy to emphasise its responsibility through diplomacy and sustainable energy investments, in the process buttressing its role as a global powerhouse and widening its influence on partner countries.

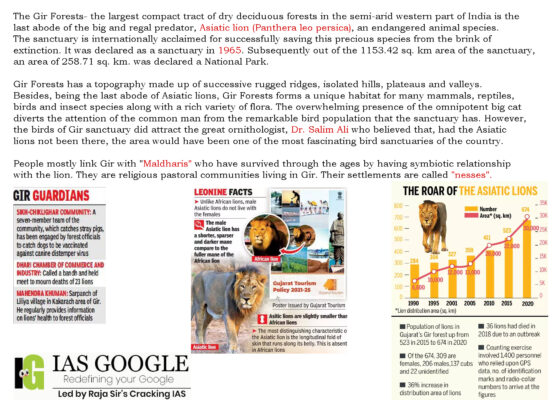

- The establishment of the International Solar Alliance (ISA) in November 2015 is an example of India’s progressive and cooperative climate engagement.

- The alliance, set up jointly by India and France during the Paris Agreement talks, is a treaty-based, member-driven forum aimed at trans-regional solar energy cooperation to both reduce fossil fuel dependence and bring about a more equitable and just energy order. Most of ISA’s members are countries in Africa, with the continent contributing 36 of the 101 ratified members.

- The global energy system is dominated by fossil fuels. Energy-related GHG emissions increased nearly 20 percent in Africa between 2008 and 2017, albeit starting from a very low initial level relative to other developing economies.

- Energy demand in African economies is expected to nearly double by 2040, as populations grow and living standards improve. Without a climate policy and transition to renewable energy sources, Africa’s share in global energy-related carbon emissions is projected to increase 3–23 percent by 2100.

- Enabling developing economies to decouple their energy consumption from their GHG emissions by replacing carbon-intensive fossil fuel use with renewable solar energy is one of ISA’s cardinal goals.

- Energy is essential for development in the contemporary world— one might say as necessary today as air, water, and earth; it is vital for poverty reduction. Ensuring “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” by the year 2030 is enshrined as Goal 7 among the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- Energy is ‘secure’ if it is adequate, affordable and reliable. There are four dimensions to energy security:

- physical availability;

- economic affordability;

- accessibility from a socio-political standpoint; and

- environmental acceptability.

- The scope of energy security has also been expanded to include supply side and demand side options. Neither is met in Africa – be it in areas such as energy efficiency, or environmental sustainability (including addressing contemporary environmental concerns, especially climate change) or socio-political challenges, such as fuel poverty. More comprehensively, it also includes notions of geopolitics and social acceptability.

- Despite an abundance of energy resources, energy insecurity is a stark reality in sub-Saharan Africa. The region suffers from the most debilitating energy poverty in the world. It has the lowest energy access rates and is home to the majority of least developed countries (LDCs).

- More than 600 millions of its 1.2 billion inhabitants have no access to modern energy services. Approximately 120 million households lack access to adequate electricity, and it is projected that 60 millions of them will continue to lack such access even after 2030. The appalling state of energy generation and distribution has continued to stifle economic growth and sustainable development in the region.

- India and sub-Saharan Africa share the misfortune of being disproportionately vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. They are responsible for only a small share of the historical, cumulative global GHGs, and yet they face the sharpest consequences.

- Indo-African relations have consolidated over the years beyond the movement against colonialism and racial discrimination, to increased trade and investment, and scientific and technological cooperation.

- One shared characteristic of the global commons is their close association with scientific discovery and development of technological capability. The ‘leapfrogging’ hypothesis postulates that low-income countries can expand their economies with modern, low-carbon technologies without relying on conventional fossil fuels as the advanced countries did while they were developing.

- Knowledge and technology transfer is thus a critical part of India-Africa collaboration in energy security. Such transfer is critical and urgent for the paradigm shift to happen—from fossil fuel energy sources to renewables.

- India is a model in the renewable energy sector. The country’s path towards a more sustainable energy future, distinguished by the use of renewable sources, offers several lessons.

- The country has over 35 GW of cumulative solar installations, with a target of 100 GW and 300 GW of solar energy capacity by 2022 and 2030, respectively. Moreover, the country’s installed wind energy capacity stands at 39.2 GW and is projected to increase by another 20 GW in the next five years.

- India continues to play a leading role in Africa’s energy security by providing and supporting access to clean energy through renewable energy technologies. Some of these developmental efforts, specifically in solar energy, are as follows:

- Training and empowering illiterate and semi-literate Malawian women under the ‘Solar Mamas’ rural electrification project to become solar engineers and simultaneously electrify their rural communities;

- Facilitating construction of power transmission lines in Kenya;

- Supporting solar electrification at primary schools in Zambia;

- Assisting a self-help electrification project in Ghana;

- Backing a solar-diesel hybrid rural electricity project in Mauritania; and

- Setting up solar photovoltaic module manufacturing plants in Mozambique.

- SDG Target 7.2 aims to “substantially increase the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix” by 2030. This target, and the increasing global demand for energy security and sustainable development has made it imperative for Africa to engage in a paradigm shift from fossil fuel energy sources to a clean solar powered energy system.

- Historically, economic development is strongly correlated with increasing energy use and growth of GHG emissions. Solar energy decouples such correlation, contributing to climate action and sustainable development. Such decoupling calls for three crucial technological changes:

- replacement of fossil fuels with solar energy;

- energy savings on the demand side; and

- improved efficiency in energy production.

- Increased energy consumption is a measure of reduced poverty and enhanced economic growth, particularly in developing nations. Renewable solar energy improves energy services for the rural poor and alleviates poverty in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Mitigating climate change, enhancing energy security, and alleviating rural poverty can all be complementary in Africa through transition from fossil resources to solar energy systems. Solar energy has been proposed as one means of improving energy security.

- In addition to being a favourable influence on a country’s energy mix, it is compatible with energy security targets of accessibility and acceptability. The availability of solar radiation in any region is less susceptible to changes in geographic and meteorological conditions and is, therefore, largely evenly distributed during daylight hours.

- Market and political forces cannot disrupt the sun, unlike oil and gas supplies. The global distribution of solar energy is more evenly spread than fossil fuels; therefore, its increased use will lessen the impact of geopolitical conflicts on energy security.

- Solar energy is also more amenable to distributed production, which is inherently more secure than the fossil fuel paradigm. These sustainable and reliable features are relevant to usher in an era of energy democracy, where a network of decentralised prosumer systems will play the role once dominated by large-scale power generators.

- Solar energy is one of the cleanest sources of energy with remarkable environmental, social, and economic benefits for society. Immediate and long-term impacts of solar home systems enrich all kinds of livelihoods assets—human, social, financial and physical.

- Solar energy also has positive impacts on household savings’ capability, health, education and women’s economic productivity and empowerment, thereby playing an important role in the implementation of SDGs.

- A recent review found that solar energy technologies improve energy access, security, and resilience, create employment along their value chain, reduce energy dependence on imports, improve public health, and afford users greater freedom to deploy electricity for personal and communal benefits.

- Further, it has been proven that solar technologies are suitable options for achieving sustainable agriculture and food security in distant rural areas. Indeed, solar energy has helped build pandemic-resilient livelihoods in the face of the disruptive effects of COVID-19.

- The outcome of India’s solar bet will radically affect the chances for success of Modi’s prized “Power for All” and “Make in India” initiatives. The use of solar innovation to meet India’s energy goals may well determine whether India is able to supply electrical power for all and have enough energy to support increased manufacturing output.

- India’s leadership on solar may provide a way for it to surge to the head of the pack on energy and the environment. However, the ultimate success of India’s big bet on solar will require additional research, available financing, and viable solar projects that will tie together the aforementioned research and financing to benefit consumers.

- India’s dream is to transform a portion of the solar radiation with which it is bombarded (some 150,000 gigawatts per year) into usable electricity. The difficulty has been the cost of this transformation – particularly in comparison to the cost of power from India’s large supplies of low caloric, dirty coal and lignite.

- Africa is often referred to as the ‘Sun Continent’—the continent where solar radiation is greatest. The continent is located between latitudes 37°N and 32°S and spans a vast area that crosses the equator and both tropics.

- The solar energy potential of Africa is arguably limitless. It is observed that, with falling solar generation costs over the past decade, solar can be the cheapest source of electricity in Africa.

- The total solar potential of all countries in sub-Saharan Africa is about 10,000 GW. Solar potential is fairly distributed across all the countries, with an average of 6 kilowatt hours (kWh) of solar energy per sq m available per day.

- A joint study by custodian agencies of SDG7 found that 49 percent of the 105 million people who had access to off-grid solar solutions in 2019 resided in sub-Saharan Africa. A significant portion of Africa currently uses solar energy to meet relatively basic needs like lighting, charging mobile phones, and powering low-capacity appliances.

- Technological developments, falling costs of renewable energy, innovative approaches, network effects, and digitization are opening new opportunities and making an indisputable business case for renewables in Africa.

- The biggest options for solar power generation in Africa are photovoltaic (PV) and concentrated solar power (CSP), as well as small-scale PV systems suitable for off-grid power generation. The technical potential of solar PV across Africa has been estimated at 6.5 petawatt hours (PWh) a year, while that of CSP is approximately 625 PWh a year.

- Both PV and CSP technologies are crucial for rural communities in Africa given their diverse potential uses ranging from energy generation, to agriculture, food processing, waste treatment, and water supply.

- Most African countries have yet to effectively utilise the abundant solar energy available to them.

- The newness of the technology, the relatively high cost, especially for CSP (and despite the overall drop in solar module prices);

- Insufficient and expensive domestic finance; unstable and weak economies; problems of social acceptance and weak institutions;

- Lack of supportive policies and legal frameworks; and inadequate technical and human resources.

- Other constraints include the limited capacity of customers to afford solar products, market uncertainty (which impacts business running), high costs of serving last-mile populations, cash-flow issues stemming from paucity of working capital, and instability in the political and economic environment.

- Strengthening the institutional and regulatory framework,

- Capacity building,

- Harmonising financial resources,

- Improving the security and political environment to attract investors.

- Countries participating in the Scaling Solar Applications for Agriculture programme include Mauritius, Senegal, Sudan, and Uganda.

- They have all received solar pumps to replace diesel-fuelled agricultural pumps for irrigation.

- The ambitious ‘One World, One Sun, One Grid’ initiative of Indian Prime Minister led to the birth of the ISA at the 2015 UN Conference of Parties 21 (COP21) in Paris.

- The formation of ISA underlined India’s presence as a dominant global force in the challenging politics of climate change.

- The multilateral treaty status accorded to ISA by the UN came into force on 6 December 2017. ISA was proposed as a multi-country partnership organisation with membership from the ‘sunshine belt’ countries lying fully or partially between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. (The ambit has been subsequently expanded to include several European countries and the US as well.)

- The goal is to mobilise more than USD 1 trillion in investments to set up 1,000 GWs of solar installations globally, thereby making clean power affordable and universally accessible by 2030.

- Apart from having member states, ISA also grants ‘partner organisation’ status to entities that can help it achieve its objectives.

- It seeks to provide a collaborative platform to leverage the technical expertise, financial capacity, and global networks of these partner organisations to scale up deployment of solar energy technologies to meet the energy needs of member countries in a safe, convenient, affordable, equitable, and sustainable manner.

- It provides a platform for the global community, including transnational institutions, multilateral development banks (MDBs), development finance institutions (DFIs), institutional investors, private and corporate organisations, industries, and stakeholders.

- The aim is to make positive contributions to the common goals of improved energy access, enhanced energy security, and provision of more opportunities for better livelihoods in rural and remote areas.

- Despite the fall in solar module prices in the past decade, solar energy is still a capital-intensive proposition that comes with risks and uncertainties.

- Yet, without state funding, ISA’s de-risking efforts have mobilised substantial private investments in solar technologies in developing countries. ISA’s risk pooling and demand aggregation from multiple projects within and across countries has helped reduce risks for investors and lowered both cost of borrowing and capital costs.

- ISA has established a Common Risk Mitigation Mechanism (CRMM), along with other stakeholders, to act as an insurance pool for financiers. The USD1-billion guarantee from this mechanism could attract up to USD15 billion in investments, which could set up 20 GW of solar PV capacity in more than 20 countries.

- Another such initiative is the Sustainable Renewables Risk Mitigation Initiative (SRMI), launched at COP24 in 2018 by ISA and some of its partners. The objective is to leverage private investments to support governments in developing, financing and implementing sustainable solar programmes and projects.

- The goal of SRMI is to mobilise USD 850 millions of concessional finance to unlock 8 GW of renewables which can provide access to reliable electricity in over 20 developing countries including Botswana, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Mali, and Namibia by 2025.

- Following the first summit of ISA held in March 2018 in New Delhi, India announced assistance of USD1 billion for the implementation of solar power projects across 10 African countries. These projects include setting up solar PV power plants, mini-grid and off-grid plants, irrigation systems, rural electrification, street lighting, and solar-powered urban infrastructure, including hospitals, schools and government establishments.

- ISA has launched three flagship programmes—Scaling Solar Applications for Agriculture, Affordable Finance at Scale, and Scaling Solar Mini-grids. Two more are in the pipeline: Scaling Residential Rooftop Solar and Scaling Solar E-mobility and Storage.

- Scaling Solar Applications for Agriculture focuses on providing greater energy access and sustainable irrigation solutions to farmers in member countries. It also supports the development of solar energy linked cold-chains and cooling systems for agricultural use.

- Affordable Finance at Scale aims to leverage private sector investments to promote the development of bankable solar programmes in developing countries. The Regional Off-Grid Electrification Project seeks to accelerate access to electricity in the 19 countries of West Africa through the use of stand-alone solar photovoltaic systems.

- ISA is working with MDBs and DFIs to deploy innovative financial instruments to scale-up low-cost financing for solar investments.

- ISA also has a Solarising Heating and Cooling Systems programme, where, working with the Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC), it has piloted solarised and efficient cold food chains in Nigeria.

- The development of solar powered pack houses and cold storages in Senegal and Ghana is being financed by a Euro 1.3-million grant from the French Facility for Global Environment.

- The project focuses on developing innovative business mechanisms to make sustainable cooling infrastructure available at low cost to all. The objective of the programme is to solarise the growing thermal demand from commercial, industrial, and residential sectors.

- An initial area of focus is developing solar-powered cold chains for safer and longer preservation of food, significantly reducing post-harvest food loss and potentially doubling farmers’ incomes.

- ‘Light Up and Power Africa’ is part of the African Development Bank’s (AfDB) ‘New Deal on Energy for Africa’ scheme to support fast and affordable means of delivering energy access.

- AfDB and ISA are working together to create new financial instruments. They seek to provide local lenders with risk mitigation instruments to support distributed energy service companies and thereby accelerate off-grid energy access in sub-Saharan Africa at scale.

- ISA provides technical assistance and knowledge transfer to support both off-grid solar projects and large-scale solar independent power producers. The aim is to provide an additional 10,000 MW of electricity to 250 million people in African ISA member countries. Once this is accomplished, the region will be the world’s largest solar powered zone.

- The concept of sustainable livelihood requires shifting the focus of environmental action towards people and livelihood activities to improve the quality of life of the poor. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) has increasingly been employed in policy and development intervention designs to assess the impact of off-grid electrification by solar energy, especially in developing countries.

- This framework shows how sustainable livelihoods are achieved through access to a range of livelihood resources—natural, economic, human, and social capital. The SLA is a valuable tool to evaluate the activities of ISA in sub-Saharan Africa, beyond geopolitics and global commons, towards enhancement of sustainable livelihoods among rural households in the region.

- Electricity generated from solar can be used to power household appliances such as televisions, radios and mobile phones, which increase rural communities’ access to information and provide security updates to communities in crisis, thereby contributing to the people’s social capital.

- Increased incomes from agricultural practices positively impact economic growth, as well as human capital, through access to quality education, thereby contributing further to sustainable livelihoods.

- The International Solar Alliance is the first international organization headquartered in India and aims to promote solar electricity.

- India is using the ISA as an instrument for geopolitical influence.

- India's domestic model of solar scale-up and plans for the ISA to pool credit risk provide leadership opportunities.

- India's limited financial capacity and solar manufacturing capability reduce India's leadership potential.

- Whether the ISA can enhance India’s geopolitical status depends on whether the ISA can offer joint gains to members.

- The International Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Report (AR6) submitted that climate change is making both agricultural and ecological droughts more frequent, severe and pervasive in Africa.

- Climate-smart, solar-powered water pumping irrigation systems help tackle challenges of frequent droughts and unreliable rainfall, leading to improved productivity and establishing resilient livelihoods in water-scarce areas.

- Improved access to solar energy ensures sustainable consumption and production, and also contributes to environmental conservation by reducing deforestation and land degradation.

- Other benefits include reduction in risk, especially among women and children, of death from indoor air pollution due to cooking by firewood. Sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest rates of primary school electrification in the world.

- Solar energy technologies can enable rapid deployment of clean, reliable and affordable energy in schools and households. It gives children in rural areas a chance to study longer and thus perform better.

- Many health facilities in the region operate with unreliable energy sources. Solar electrification of hospitals and other health facilities can help power life-saving equipment and services, and store vaccines and medical supplies better, improving access to quality healthcare and reducing the costs.

- Indeed, there is a strong link between adoption of solar energy technologies and improved human and economic capital. There is also a correlation between solar energy consumption and economic growth.

- The solar energy value chain fosters economic growth and improves employment opportunities. The use of local labour for installing, operating and maintaining solar technologies creates more jobs, too.

- Energy insecurity is a stark problem in many developing countries, including those in sub-Saharan Africa. This is particularly true for the poorer and more vulnerable populations in the rural regions. Solar energy offers potential socio-economic and environmental solutions to the energy gap. Clean and sustainable, its adoption reduces GHGs emissions—the primary cause of climate change. Solar energy also provides access to affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy for all by 2030, as set out in the UN’s SDG 7.

- Collaboration on energy is a critical aspect of India–Africa partnership, as India’s investments in sustainable energy development in sub-Saharan Africa through ISA continue to strengthen its influence in the region. While most of ISA’s efforts in sub-Saharan Africa are in their initial stages, early evidence shows that the existing framework of Indo-African cooperation, and the ISA in particular, are indeed helping the region to address the fundamental challenges of climate change, energy access and energy security, while contributing to the achievement of SDG 7.

- For ISA to realise its lofty objectives of improving the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of African citizens, it is imperative for elected policymakers in the different countries to ensure their policies are complementary, so they can jointly address the developmental issues of climate change mitigation, energy security, and sustainable livelihoods.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- There were six sessions covering Growth & Investment potential in Technical Textiles, Waster material applications in technical textiles, Geo-textiles, Agro-textiles, Specialty fibres, Protective textiles, Sports textiles, and medical textiles.

- The Government highlighted the importance of technical textiles for boosting the economy of the country and its potential to contribute to the Hon’ble Prime Minister’s Mission on ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ through various flagship missions and schemes of the Government of India, including Jal Jivan Mission, Mission of Integrated Development of Horticulture, National Health Mission, National Investment Pipeline, and strategic sectors are expected to create untapped opportunities in the domestic market.

- It further emphasized that it is the right time to maximize investment, employment, and women’s participation in the industry.

- It highlighted various factors to drive the domestic technical textiles market including rising incomes, expanding infrastructure and construction, growing healthcare, and increasing global market, among others.

- R&D in technical textile projects augmented through usage of Bamboo fibres hold strong potential in India. In addition, tremendous growth opportunities and prospects will be created in the areas of Space Technology, Energy, Drones, among others.

- Indian market in technical textiles has enormous scope to grow further and capture the global market on the back of the National Technical Textiles Mission, PLI, and PM MITRA schemes.

- The Indian Technical Textiles market is poised to grow at the rate of 8% vis-à-vis world growth rate at 4% setting the stage for enormous opportunities.

- Technical textiles are engineered products with a definite functionality. They are manufactured using natural as well as man-made fibres such as Nomex, Kevlar, Spandex, Twaron that exhibit enhanced functional properties such as higher tenacity, excellent insulation, improved thermal resistance etc.

- These products find end-use applications across multiple non-conventional textile industries such as healthcare, construction, automobile, aerospace, sports, defence, agriculture.

- Taking cognisance of technological advancements, countries are aligning their industries to accommodate technical textiles. This shift is evident in India's textile sector as well, moving from traditional textiles to technical textiles.

- The invention of speciality fibres and their incorporation in almost all areas suggest that the importance of technical textiles is only going to increase in the future.

- Technical textiles have seen an upward trend globally in recent years due to improving economic conditions. Technological advancements, increase in end-use applications, cost-effectiveness, durability, user-friendliness and eco-friendliness of technical textiles has led to the upsurge of its demand in the global market.

- Indutech, Mobiltech, Packtech, Buildtech and Hometech together represent 2/3rd of the global market in value.

- The demand for technical textiles was pegged at $ 165 Bn in the year 2018 and is expected to grow up to $ 220 Bn by 2025, at a CAGR of 4% from 2018-25.

- The Asia-Pacific has been leading the technical textiles sector by capturing 40% of the global market, while North America and Western Europe stand at 25% & 22% respectively.

- Asia-Pacific has seen a tremendous growth in this sector and captures the largest market share due to rapid urbanisation and technological advancements in medical, automobile and construction industries. This is further catalysed by easy production, low-cost labour and conducive government policy support.

- The European Union was leading in consumption from 2007-13, owing to Techtex producers' proximity to large European car manufacturers. The product nomination process was unique to Europe and led to the presence of European Techtex products in different export markets worldwide.

- European Techtex manufacturers were able to establish a strong and unique position due to their R&D efforts and operational efficiency. However, production declined since 2013, particularly in France and Spain, due to weak demand in the automobile and construction sector.

- The current Indian technical textiles market is estimated at $ 19 Bn, growing at a CAGR of 12% since past five years. It contributes to about 0.7% to India’s GDP and accounts for approximately 13% of India’s total textile and apparel market.

- Availability of raw materials such as cotton, wood, jute and silk along with a strong value chain, low-cost labour, power and changing consumer trends are some of the contributing factors to India’s growth in this sector.

- India’s technical textiles market shows a promising growth of 20% from $ 16.6 Bn in 2017-18 to $ 28.7 Bn by 2020-21, as per the Baseline Survey of technical textile industry by Ministry of Textiles.

- India’s exports of technical textiles in 2018-19 is estimated at $ 1.9 Bn, which has grown at a CAGR of 4% over the past four years.

- India’s imports of technical textiles have increased at a CAGR of 8% within the last four years, from $ 1,635 Mn to $ 2,209 Mn in 2018-19.

- Packtech, Indutech and Hometech are the largest exported segments having a combined share of around 85% of the total exports of technical textiles.

- Products such as flexible intermediate bulk containers, tarpaulins, jute carpet backing, hessian, fishnets, surgical dressings, crop covers, etc. that are not very R&D intensive have been able to capture a substantial share in the overall exports.

- Unlike the conventional textile industry in India, which is highly export intensive, the technical textile industry is still import dependent. Products such as diapers, polypropylene spun-bond fabric for disposables, wipes, protective clothing, hoses, webbings for seat belts etc. form a substantial part of the country’s imports.

- In India, production is largely concentrated in the small-scale segments such as canvas tarpaulin, carpet backing, woven sacks, shoelaces, soft luggage, zip fasteners, stuffed toys, fabrication of awnings, canopies and blinds etc.

- The technical textiles sector in India is heavily dependent on import of speciality fibres. The next segment highlights some of the speciality fibres and their strategic importance.

- Harmonized System of Nomenclature (HSN) Codes for Technical Textile

- In 2019, the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India dedicated 207 HSN codes to technical textiles to help in monitoring the data of import and export, in providing financial support and other incentives to manufacturers.

- The purpose of this classification is to increase international trade, and enable the market size to grow up to $ 26 Bn by the year 2020-21.

- 100% FDI under Automatic Route Government of India allows 100% FDI under automatic route. International technical textile manufacturers such as Ahlstrom, Johnson & Johnson, Du Pont Procter & Gamble, 3M, SKAPS, Kimberly Clark, Terram, Maccaferri, Strata Geosystems have already initiated operations in India.

- Technotex India It is a flagship event organised by the Ministry of Textiles, in collaboration with Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) and comprises of exhibitions, conferences and seminars with participation of stakeholders from across the global technical textile value chain.

- National Technical Textiles Mission With a view to position the country as a global leader in technical textiles, the CCEA has given its approval to set up a National Technical Textiles Mission with a total outlay of $ 194 Mn in February 2020.

- The Mission shall be set up for a four-year implementation period from FY 2020-24 and will have the following four components:

- Component - I (Research, Innovation and Development)

- Component – II (Promotion and Market Development)

- Component - III (Export Promotion)

- Component- IV (Education, Training, Skill Development)

- Scheme for Integrated Textile Park (SITP)

- To boost entrepreneurship by providing financial support and state-of-the-art infrastructure, the scheme was launched in 2005 and has recently been extended for the period between 2017-20.

- The project cost will cover common infrastructure and buildings for production/support activities (including textile machinery, textiles engineering, accessories, packaging), depending on the needs of the ITP.

- Each project will normally be completed in 3 years from the date of release of the first installment of a government grant.

- SITPs dedicated to technical textiles, namely, Pallavada Technical Textiles Park (Tamil Nadu), Vraj Integrated Textile Park Ltd. (Gujarat), Mundra SEZ Integrated Textile and Apparel Park Pvt. Ltd (Gujarat), Gouthambudha Textile Park Pvt. Ltd (Andhra Pradesh) and Great Indian Linen & Textile Infra Structure Co. (P) Ltd (Tamil Nadu) are functional in the country.

- Centres of Excellence Ministry of Textiles had launched Technology Mission on Technical Textiles (TMTT) with two mini-missions for a period of five years from 2010-15which entailed the creation of the following eight Centres of Excellence to provide infrastructure support, lead research and conduct tests of various technical textiles.

- The Mission shall be set up for a four-year implementation period from FY 2020-24 and will have the following four components:

- The Ministry of Textiles implemented ATUFS in January 2016, for a period of seven years. ATUFS’s larger objective is to improve exports and indirectly promote investments in textile machinery. Under ATUFS, technology upgradation and CIS are offered to entities that are engaged in manufacturing textile and technical textile products under the guidance of TAMC (Technical Advisory Monitoring Committee).

- Entities or segments that engage in manufacturing of technical textiles are provided a CIS of 15% or an upper limit of $ 3 Mn.

- If the eligible capital investment is 50% of the project cost, then it is 10% or an upper limit of $ 2 Mn.

- The scheme is credit linked and shall be availed on the term loan from a notified lending agency with minimum 50% of the total eligible machinery cost under the project.

- In order to develop the textile industry into a strong and vibrant one, meet the growing needs of the people and contribute to sustainable growth of employment and economic growth, it is imperative that we have a sound and dynamic National Textile Policy. The National Textile Policy was released in 2000. With the textiles industry growing by leaps and bounds, there is a need for revising and updating the national textiles policy.

- Time bound programmes should be initiated for building strong capacities with R&D facilities and to encourage their growth and development in the private sector while strategically, strengthening the public sector to complement the private initiatives where it is essential.

- Adoption of a PPP model by the government will build trust and encourage the industry to work towards the common goal resulting in positive outcomes.

- Subsidies and incentives should be offered to set up export focussed technical textile manufacturing hubs.

- Policy should initiate steps taken to identify potential organisations and promote international standardisation to meet the demands of the global market. To bolster the existing BIS, a new department dedicated to fast-tracking standardisation of technical textiles must be formed.

- The policy must address the need for ease in licensing and regulatory requirements which will boost foreign investments and facilitate the development of next generation technologies in this sector.

- Custom duties on vital inputs for technical textiles are very high leading to an exponential rise in the final cost of the product. Hence, customs duty on raw materials should be further reduced to remove the existing anomaly.

- In order to encourage the spirit of innovation and a new breed of young textile innovators, the government should frame a scheme to provide various fiscal and non-fiscal incentives to develop and promote incubation centres, provide seed money for startups, scale up funding and other support required by the startup units.

- To promote consumer awareness, it is important to instil confidence to encourage adoption of technical textiles in the market. Therefore, the government should encourage user education and various benefits that the products can bring to their lives in terms of convenience and lowering costs.

- To explore the potential of the technical textiles and facilitate their public procurement, mandatory use of technical textiles in priority sectors such as defence, agriculture, medical and construction that are already low hanging fruits should be included in the draft.

- Growth of this sector has to be made sustainable and in particular, ensure environmental sustainability through green technologies, energy efficiency, and optimal utilisation of natural resources and restoration of damaged / degraded ecosystems.

- Small, medium, large scale and mega industries should be provided incentives and subsidies for investments in setting up waste management systems, pollution control, health and safety standards and water conservation etc.

- Market development assistance should include branding, design development, product diversification, assistance in standards and compliances especially for the backward areas.

- The National Skill Development Initiative launched by the Government of India has provided a renewed thrust to build productive capacities. This must integrate skill building programs and capacity building workshops and provide incentives and subsidies for the establishment of such centres.

- One of the key instruments that must be included in the policy to catalyse the growth of technical textiles is the establishment of textile parks and cluster development. These should be developed and benchmarked with the best textile manufacturing hubs in the world. This will also help us to meet the increasing demand for creating world-class facilities and providing gainful employment opportunities.

- The entire process of clearances by Central and State authorities for the establishment of technical textile parks and clusters should be progressively made web enabled. Efforts should be made to reduce the burden of compliance. Single window clearances and fast track approvals should be part of the issue resolving process.

- The importance of R&D in technical textiles should be driven through academia wherein students of textile engineering in various universities, institutions, polytechnics and applied sciences are provided learning and advanced experimental knowledge in specialised scientific subjects.

- The formation of a ‘National Centre of Research in Technical Textiles’ may be proposed as a first step towards creating a formal institutional structure. This may be established within an existing institution or as a separate entity.

- In addition to monitoring long and short-term research, the centre should be encouraged to create international collaborations with the leading institutes around the world.

- Standards form a critical part in the regulatory framework by helping the industry deliver high quality products, build trust and improve our export ability. Product specification leads to consumer empowerment, enhances product awareness and creates a level playing field for industry players across the domain.

- One of the effective ways to bridge this technological gap is to bring in Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). Some global companies may consider bringing their technologies to India for supplying into domestic and overseas markets.

- Technical textiles industry is at a nascent stage in India and hence, holds a vast potential for growth. With the government’s aim to create world class infrastructure in the country, in addition to the implementation of several policies and schemes to boost the textile sector, technical textiles is poised for growth.

- The Ministry of Textiles and Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship’s (MSDE) could collaborate on the creation of skilling universities across the country to focus on technical textiles. This could be in cognisance with the Industry Revolution 4.0 which shall demand a completely different skill set from the upcoming workforce.

- As a result, it is essential for a skilled university to conduct and/or outsource regular demand-assessment studies (preferably every five years) within its jurisdiction as well as refer to similar studies carried out in other parts of the world.

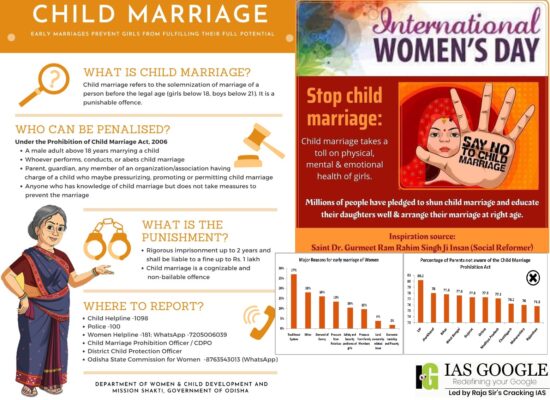

Key Statistics Related to Child Marriage

Key Statistics Related to Child Marriage

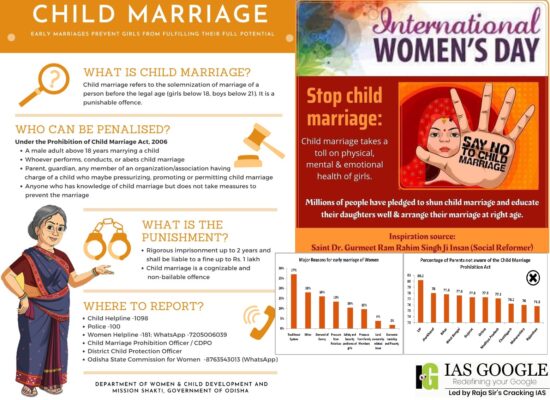

- Child marriage is still common in India, with most Indian adolescents getting married before the age of 18, the latest report by prestigious medical journal The Lancet has revealed.

- The study estimated that 650 million girls and women alive today got married in childhood: About half of them in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India and Nigeria. The levels of child marriage were the highest in sub-Saharan Africa, where 35 per cent young women were married before 18, according to April 2020 UNICEF report.

- The report says that child marriage in India is declining “very slowly”. As per the report, 47 per cent of women are married before 18 years.

- The highest prevalence is in five states: Madhya Pradesh (73 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (71 per cent), Rajasthan (68 per cent), Bihar (67 per cent), and Uttar Pradesh (64 per cent).

- The urban–rural differential is substantial, with the rate of rural girls marrying at ages younger than 18 years being nearly twice the rate of urban girls.

- The report adds that girls who marry before 18 years, report physical violence twice as often and sexual violence three times as often as those marrying later.

- At least 10 million more girls are at a risk of being forced into marriage due to the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, according to a new analysis by United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

- Even before the pandemic, as many as 100 million girls were at the risk of child marriage in the next decade, despite significant reductions in several countries in recent years.

- The proportion of young women who were married as children had declined in the last decade — to 20 per cent from 25 per cent — the equivalent of some 25 million marriages averted.

- There was no evidence of child marriage during the Rigvedic period. If we go by the ancient texts, the Manu smriti puts the onus on a father and says that he must marry her daughter before puberty, or within three years of reaching puberty.

- According to Tolkappiyam, a Tamil text, the correct age to get married for a boy is sixteen years, and for a girl is twelve years. There is also evidence which suggests that the Muslim invaders introduced this culture of child marriage when they were ruling India, and it further lowered the status of women.

- The practice of child marriage in India may be dates back to the ancient period however, during the Muslim rule in India, the practice of child marriage was found more prevalent in northern states.

- During the early medieval period, child marriages were prevalent due to changing socio-economic conditions of the country.

- All India Women’s Conference, National Council of Women in India and Women’s India Association were the organizations who fought against the evil of child marriage.

- Thus, to eradicate the menace, the British Government took steps along with Indian Social Reformers such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, etc.

-

- The Child Marriage Restraint Act, also called the Sarda Act, was a law to restrict the practice of child marriage.

- It was enacted on 1 April 1930, extended across the whole nation, with the exceptions of some princely states like Hyderabad and Jammu and Kashmir.

- This Act defined the age of marriage to be 18 for males and 14 for females.

- In 1949, after India's independence, the minimum age was increased to 15 for females, and in 1978, it was increased again for both females and males, to 18 and 21 years, respectively.

- Low level of education of girls

- Lower status given to the girls and considering them as financial burden

- Social customs and traditions

- Money marriage refers to a marriage where a girl, usually, is married off to a man to settle debts owed by her parents.

- A bride's price is the amount paid by the groom to the parents of a bride for them to consent to him marrying their daughter. In some countries, the younger the bride, the higher the bride's price. This practice creates an economic incentive where girls are sought and married early by their family to the highest bidder.

- School closures, job losses and increased economic insecurity, the interruption of support services for families and parental deaths due to the pandemic put the most vulnerable girls at increased risk of child marriage, the report titled COVID-19.

- Girls married off in their childhood are more likely to experience domestic violence and are less likely to remain in school, the study highlighted.

- Child marriage increases the risk of early and unplanned pregnancy, thereby increasing the risk of maternal complications and mortality.

- The practice can also isolate girls from family and friends and exclude them from participating in their communities, taking a heavy toll on their mental health and well-being, the report added.

- Infants born to mothers under the age of 18 are 60% more likely to die in their first year than to mothers over the age of 19. If the children survive, they are more likely to suffer from low birth weight, malnutrition, and late physical and cognitive development.

- A study showed high fertility, low fertility control, and poor fertility outcomes data within child marriages. 90.8% of young married women reported no use of a contraceptive prior to having their first child. 23.9% reported having a child within the first year of marriage. 17.3% reported having three or more children over the course of the marriage. 23% reported a rapid repeat childbirth, and 15.2% reported an unwanted pregnancy. 15.3% reported a pregnancy termination (stillbirths, miscarriages or abortions). Fertility rates are higher in slums than in urban areas.

- Odisha launched a state strategy action plan in 2019 to make the state child-marriage free by 2030.

- Every district has to adopt the same process for declaring villages child-marriage free. The process is as follows:

- A minimum time period of two previous years, where no child marriage took place, is one of the major indicators

- Villages fulfilling this criterion approach the district administration, along with a village resolution for the declaration.

- In response, a district-level team carries out proper verification and recommends the district magistrate-cum-nodal officer to declare the village to be child-marriage free.

- As a part of this programme, many districts developed a database of adolescents and started keeping records of all marriages at the village level. Ganjam district alone recorded 48,386 marriages in the last two years, out of which 26 are child marriages.

- Data of marriages taking place in each village in Subarnapur district was also submitted to the district magistrate through the block development officer on a monthly basis.

- A thorough database of marriages taking place in the last two years has been prepared with the direct supervision of the district magistrate in Nabarangpur district as well.

- There are many such bodies tracking each and every marriage in the villages to put a stop to the malpractice of child marriage. Tracking marriages is a great tool to ensure no child marriage takes place in any village declared child-marriage free.

- Apart from this, capacity-building of adolescents, engaging with different stakeholders for socio-behavioural changes, felicitation of the children and parents who have refused to marry off their children, capacity-building of duty bearers are constantly going on to build a preventive and enabling environment.

- Over time, the state is witnessing an increase in reporting child marriages and responding to them accordingly, reflecting the responsiveness of the system and the duty bearers.

- The attention the issue is getting from the state, if continued, can eradicate the malice in the entire state in the desired period. Drives to rid villages of child marriage created scope for people’s participation. This campaign also has been a stimulus for many to take the mission forward.

- Concerns Related to Odisha's Ganjam Model against Child Marriage

- There have been fewer interventions in urban areas compared to rural areas.

- This is despite the fact that children in slums are more vulnerable to elopement and child marriage.

- There is no institutional mechanism prepared yet in urban areas like the child protection committees in rural regions.

- The police still do not consider solemnisation of child marriage as a significant crime. Hence registration of a FIR is still not a priority for such cases.

- Law on Child Marriage in India: Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006.

- It allows anyone who was a child at the time of getting married to legally undo it;

- It provides for maintenance for the girl in a child marriage;

- It treats children born out of child marriages to be legitimate, and makes provisions for their custody and maintenance; and

- It considers certain kinds of child marriages where there was force or trafficking as marriages which never happened legally.

- You can go directly to a District Court and make an application – the judge can pass an order directing the people involved to not take part in the child marriage.

- You can go to a Child Marriage Prohibition Officer for help with annulling a child marriage.

- To make the campaign more effective, the state needs to review and re-strategise a few aspects. It has been observed that the crusade has been successful, wherever the district magistrate attended to the matter personally.

- There is a need to change this idiosyncratic approach to a structure-centric approach. This will be helpful in sustaining the program, as well as to increase its spread.

- This form should be prioritised and such committees should be made functional at the ward- and city-level, involving the urban local bodies.

- The Juvenile Justice Care and Protection Act, 2015 can be helpful in building a preventive environment for combating child marriage.

- Conditional cash transfers are the most successful intervention for improving girls’ retention or progress in school and delaying child marriage.

- Employment can be offered to low-wage labourers, insurance coverage provided to workers in the healthcare sector, and the healthcare infrastructure strengthened. Such economic policies can protect girls from marriage.

- It is the duty of the Government to promote long-term policies to develop the rural areas and impart education in remote areas, to uplift the poor living conditions and enhance instructive projects of education and health care facilities.

- The situation regarding child marriage is gradually changing. People are becoming aware and informing about the incidences of child marriage in their respective localities to the police, Childline, CMPO and the like. State governments are trying to reduce child marriages to zero by 2030.

- The process of social change is dynamic and continuous. There have been many successful experiments in the past. With increased people’s participation and responsive governance, this pursuit of making a state child-marriage free will also be successful.

Provisions of New Drone Policy

Provisions of New Drone Policy

- The provisions under Aircraft Rules, 1937 will not be applicable to drones weighing up to 500 kg. This is a significant change because Aircraft Rules, 1937 are specifically applicable for passenger aircraft.

- A significant number of people in India fly nano and micro drones, including operators of model aircraft. One can see drones being used at marriage parties as well as during shooting of shows and movies.

- People flying these drones and model aircraft now do not need a drone pilot license. This singular step can boost employment. Being a drone pilot is considered one of the coolest things today.

- Drone imports will still be controlled by the Directorate General of Foreign Trade or DGFT. Initially, this could be seen as bit of an impediment for entrepreneurs who are dependent on foreign imports of certain drone parts. However, in the long run, this provision could bolster manufacturing of these parts in India and then even exporting them.

- The government, however, can currently look at relaxing the rules for import of drones/drone parts and tighten the norms as time goes by. Such a policy could support the nascent drone industry in India. I would recommend that drone imports controlled by DGFT could be done away with for the time being.

- Creation of drone corridor is likely to change the face of the Indian economy. Logistics operation, last-mile connectivity, transporting goods between two towns and the cost of connectivity, in general, are set to change dramatically.

- The section on drone research and development is futuristic. If harnessed and nurtured properly, India can see the emergence of many centres of excellence for drones and drone technologies.

- Government needs to create an equivalent of ‘Silicon Valley’ for the drones so that organisations dealing with hardware, software, artificial intelligence etc. can come together and take this endeavour forward.

- A number of companies world over are working on unmanned traffic management (UTM), including an Indian company. These companies could now collaborate with the government of India to provide unmanned traffic information as well as work as service providers for tracking drones and offering drone operators a simple no permission, no takeoff (NPNT) nod.

- Third-party drone insurance could be adequate as specified in the rules. However, drones are costly equipment. Readers would be surprised to know that most of these drones cost more than a small hatchback. Therefore, owners of these drones may want to go for comprehensive insurance.

- There is a huge opportunity for insurance and insurance facilitation companies to explore this area. In the times to come, the numbers for drone insurance may well overtake the numbers for vehicle insurance, globally, since drones are set to replace many of the traditional workforce and industries.

- A ‘Drone Promotion Council’ is the need of the hour, as the draft rules rightly identify. Countries that do not board the ‘Drone Bus’ may get left behind in economic progress in near future.

- In rule 16, which specifies Registration of existing unmanned aircraft systems, for the words within a period of thirty-one days falling after the said date, the words, figures and letters on or before the thirty–first day of March, 2022, shall be substituted.

- A person owning an unmanned aircraft system manufactured in India or imported into India on or before the 30th day of November, 2021 shall on or before the thirty-first day of March, 2022, make an application to register and obtain a unique identification number for his unmanned aircraft system and provide requisite details in Form D-2 on the digital sky platform along with the fee as specified in rule 46.

- In Parts VII, VIII and Part XII dealing with Remote Pilot Training Organisation, Research, Development and Testing and Miscellaneous respectively, for the word licence wherever it occurs, the word certificate shall be substituted.

- In rule 34, which specifies Procedure for obtaining a remote pilot licence, sub-rule (4) has been omitted.

- The liberalised regime for civilian drones marks a clear shift in policy by the government to allow operations of such drones and highlights the government’s intent to allow the use of drones while at the same time ensuring security from rogue drones through the anti-rogue drone framework that was announced in 2019.

- The draft rules for the new policy were announced just weeks after a drone attack took place at an Indian Air Force base in Jammu.

- The new Drone Rules usher in a landmark moment for this sector in India. The rules are based on the premise of trust and self-certification. Approvals, compliance requirements and entry barriers have been significantly reduced.

- The new Drone Rules will tremendously help start-ups and our youth working in this sector. It will open up new possibilities for innovation & business. It will help leverage India’s strengths in innovation, technology & engineering to make India a drone hub.

- The major intent behind liberalising the drone policy in India was to make it a global drone hub.

- The policy will become so liberal that the entire concentration should be more on research and development.

- There is no sector left where drones cannot be used. The applications are law and order, defence, agriculture and so on. It will play an important role in war.

- The drone airspace map which freed up almost 85-90 per cent of India as a green zone where you could just go and fly for business or for personal needs.

- PLI scheme was notified on 30th September 2021. The total incentive is INR 120 crore spread over three financial years, which is nearly double the combined turnover of all domestic drone manufacturers in FY 2020-21.

- The PLI rate is 20% of the value addition, one of the highest among PLI schemes. The value addition shall be calculated as the annual sales revenue from drones and drone components (net of GST) minus the purchase cost (net of GST) of drone and drone components. PLI rate has been kept constant at 20% for all three years, an exceptional treatment for drones.

- As per the scheme, Minimum value addition norm is at 40% of net sales for drones and drone components instead of 50%, an exceptional treatment for drones. Eligibility norm for MSME and startups is at nominal levels.

- Coverage of the scheme includes developers of drone-related software also. PLI for a manufacturer shall be capped at 25% of total annual outlay. This will allow widening the number of beneficiaries.

- In case a manufacturer fails to meet the threshold for the eligible value addition for a particular financial year, he will be allowed to claim the lost incentive in the subsequent year if he makes up the shortfall in the subsequent year.

- More than one company within a Group of Companies may file separate applications under this PLI scheme and the same shall be evaluated independently.

- However, the total PLI payable to such applicants shall be capped at 25% of the total financial outlay under this PLI scheme.

- The Ministry of Civil Aviation launched the Digital Sky Platform24, a unique unmanned traffic management (UTM) system which will facilitate registration and licensing of drones and operators in addition to giving instant (online) clearances to operators for every flight.

- The Digital Sky Platform will enable online registration of pilots, devices, service providers, and NPNT (no permission, no take-off).

- Addressing the session on Drones for Public Good – Mass Awareness Program, organized by FICCI, Union Civil Aviation Minister said that the government’s role has changed, and it is working as an enabler, and not a regulator, looking at a new approach of evidence-based policymaking for drones.

- Union Civil Aviation Minister said technology promotion is crucial and drone technology will bring those living at the margins to the centre of development. “Drones play a crucial role in connecting the people from the length and breadth of the country.”

- Union Minister of Civil Aviation flagged off the Doon Drone Mela 2021 in Dehradun, Uttarakhand. Union Civil Aviation Minister flagged off the event with a paragliding demonstration and also interacted with the drone companies exhibiting their prototypes at the Doon Drone Mela.

- On the occasion Union Minister said, we recognise the immense opportunities which usage of drones bring in. The Government of India is working towards enabling the same with a liberalized drone policy and the launch of the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme.

- We insist that the Uttarakhand Government works towards developing Dehradun as an Aero sports and Drone Hub of India.

- Gwalior Drone Mela was organised jointly by Ministry of Civil Aviation, Government of India, Government of Madhya Pradesh, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) at Madhav Institute of Technology & Science (MITS), Gwalior.

- This is part of the series of events planned under the Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav celebration. The programme was the biggest congregation of drone manufacturers, service providers, drone enthusiasts and user communities, especially students, farmers and common man of the city.

- Programme included drone exhibition, demonstration, drone spardha, industry – user interactions and launches.

- The drone policy is a welcome change. It is a well-thought-out and simplified policy document. It is in consonance with Prime Minister Modi’s vision for India, in terms of reducing unemployment, improving ease of doing business, generating self-employment avenues, and emerging as a global leader in technology. What the future holds will entirely depend on how these rules are interpreted on the ground and how much of red-tapism we are willing to shun.

About NMCG

About NMCG

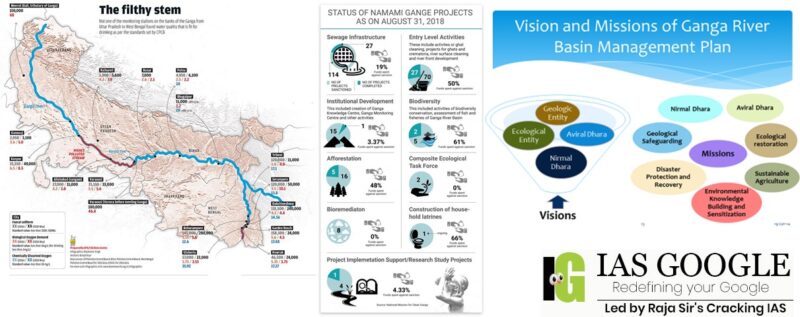

- National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) was registered as a society on 12th August 2011 under the Societies Registration Act 1860.It acted as implementation arm of National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) which was constituted under the provisions of the Environment (Protection) Act (EPA),1986.

- NGRBA has since been dissolved with effect from the 7th October 2016, consequent to constitution of National Council for Rejuvenation, Protection and Management of River Ganga (referred as National Ganga Council)

- National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) is providing financial and technical support to the States for implementing projects on diverse set of interventions like pollution abatement activities including sewage, industrial effluent, Solid Waste etc., River Front Management, Aviral Dhara, Rural Sanitation, Afforestation, Biodiversity Conservation, Wetland Conservation, Public Participation etc. for cleaning and rejuvenation of river Ganga.

- These projects are implemented by State Executing Agencies which helps to generate local employment in the States, however, the employment data are not collated and kept at NMCG.

- The Act envisages five tier structure at national, state and district level to take measures for prevention, control and abatement of environmental pollution in river Ganga and to ensure continuous adequate flow of water so as to rejuvenate the river Ganga as below;

- National Ganga Council under chairmanship of Hon’ble Prime Minister of India.

- Empowered Task Force (ETF) on river Ganga under chairmanship of Hon’ble Union Minister of Jal Shakti (Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation).

- National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG).

- State Ganga Committees and

- District Ganga Committees in every specified district abutting river Ganga and its tributaries in the states.

- NMCG has a two-tier management structure and is comprised of the Governing Council and Executive Committee. Both of them are headed by Director General, NMCG. The Executive Committee has been authorized to accord approval for all projects up to Rs.1000 crore.

- Similar to structure at national level, State Programme Management Groups (SPMGs) act as implementing arm of State Ganga Committees. Thus, the newly created structure attempts to bring all stakeholders on one platform to take a holistic approach towards the task of Ganga cleaning and rejuvenation.

- The Director General (DG) of NMCG is an Additional Secretary in Government of India. For effective implementation of the projects under the overall supervision of NMCG, the State Level Program Management Groups (SPMGs) are also headed by senior officers of the concerned States.

- The aims and objectives of NMCG is to accomplish the mandate of National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) of

- To ensure effective abatement of pollution and rejuvenation of the river Ganga by adopting a river basin approach to promote inter-sectoral co-ordination for comprehensive planning and management and

- To maintain minimum ecological flows in the river Ganga with the aim of ensuring water quality and environmentally sustainable development.

- Ganga (or the Ganges) is among the largest rivers in Asia, flowing >2,500 kms from Goumukh in Uttarakhand to the Bay of Bengal at Ganga Sagar in West Bengal, covering 26% of India’s landmass.

- In 2010, ~1.4 billion litres of untreated sewage were dumped into Ganga, according to a Hindu article published in 2011.

- Following this, in 2011, the Indian government took efforts to restore Ganga by focusing on engineering-based approaches to maintain its water quality; however, its limited efforts to involve local communities in the restoration process resulted in an unsuccessful attempt to revive the river.

- In addition, the government established the National Ganga River Basin Authority to address the issue of Ganga River at the basin level to maintain its water quality, ecological flows, biodiversity value and sustained ecosystem services.

- River Ganga has significant economic, environmental and cultural value in India.

- Rising in the Himalayas and flowing to the Bay of Bengal, the river traverses a course of more than 2,500 km through the plains of north and eastern India.

- The Ganga basin - which also extends into parts of Nepal, China and Bangladesh - accounts for 26 per cent of India's landmass.

- The Ganga also serves as one of India's holiest rivers whose cultural and spiritual significance transcends the boundaries of the basin.

- The Namami Gange Programme is a flagship initiative of the Union Government and was implemented by the National Mission for Clean Ganga. It was inaugurated in June 2014, with a budget of Rs. 20,000 (US$ 2.7 billion) to achieve two objectives, i.e., conservation and rejuvenation of Ganga.

- The main pillars of the programme are treating sewage infrastructure, achieving biodiversity, developing riverfronts, cleaning river surfaces, enabling afforestation, monitoring industrial effluents and increasing awareness among the public.

- Since the programme’s roll-out, the government has sanctioned 315 projects worth Rs. 28,862 (US$ 3.91 billion), of which 120 projects have been completed and the remaining are under various stages of development.

- The National Mission for Clean Ganga Chairman Rajiv Ranjan Mishra said, “Namami Gange mission is an integrated mission for pollution abatement as well as improvement in ecology and flow of Ganga and its tributaries. The primary focus of the mission is improving ecology and reducing pollution. We have made considerable progress in these aspects. We are now taking policy initiatives for linking economic development with ecological improvement. Clean energy & water ways, along with biodiversity, conservation and wetland development remain a priority.”

- The National Mission for Clean Ganga established the Ganga Knowledge Centre (GKC) to improve on the implementation of the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) programme.

- The main objectives of GKC are to create and manage knowledge resources including analysis and modelling of diverse data sets relevant to the Ganga River Basin; design and foster research innovation by identifying knowledge gaps, need for new ideas and supporting targeted research; and facilitate dialogue with stakeholders by involving the public and building partnerships with national and international universities/institutions, public & private entities and NGOs.

- National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) has started the Mission Clean Ganga with a changed and comprehensive approach to champion the challenges posed to Ganga through four different sectors, namely, of wastewater management, solid waste management, industrial pollution and river front development.

- NGRBA has been established through the Gazette notification of the Government of India dated February 20, 2009 issued at New Delhi with the objectives of

- ensuring effective abatement of pollution and conservation of the river Ganga by adopting a river basin approach to promote inter-sectoral co-ordination for comprehensive planning and management; and

- maintaining environmental flows in the river Ganga with the aim of ensuring water quality and environmentally sustainable development.

- NGRBA is mandated to take up regulatory and developmental functions with sustainability needs for effective abatement of pollution and conservation of the river Ganga by adopting a river basin approach for comprehensive planning and management.

- The Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation (MoWR, RD & GR) is the nodal Ministry for the NGRBA.

- The authority is chaired by the Prime Minister and has as its members the Union Ministers concerned, the Chief Ministers of the States through which Ganga flows, viz., Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal, among others. This initiative is expected to rejuvenate the collective efforts of the Centre and the States for cleaning the river.

- NGRBA functions include development of a Ganga River Basin Management Plan, regulation of activities aimed at prevention, control and abatement of pollution, to maintain water quality and to take measures relevant to the river ecology in the Ganga basin states.

- It is mandated to ensure the maintenance of minimum ecological flows in the river Ganga and abate pollution through planning, financing and execution of programmes including that of

- Augmentation of Sewerage Infrastructure

- Catchment Area Treatment

- Protection of Flood Plains

- Creating Public Awareness

- NGRBA has been mandated as a planning, financing, monitoring and coordinating authority for strengthening the collective efforts of the Central and State governments for effective abatement of pollution and conservation of river Ganga so as to ensure that by the year 2020 no untreated municipal sewage or industrial effluent will flow into the river Ganga.

- The NGRBA is fully operational and is also supported by the state level State Ganga River Conservation Authorities (SGRCAs) in five Ganga basin States which are chaired by the Chief Ministers of the respective States. Under the NGRBA programme, projects worth Rs. 4607.82 crore have been sanctioned up to 31st March 2014.

- Development of river basin management plan and regulation of activities aimed at prevention, control and abatement of pollution in the river Ganga to maintain its water quality, and to take such other measures relevant to river ecology and management in the Ganga Basin States.

- Maintenance of minimum ecological flows in the river Ganga with the aim of ensuring water quality and environmentally sustainable development.

- Measures necessary for planning, financing and execution of programmes for abatement of pollution in the river Ganga including augmentation of sewerage infrastructure, catchment area treatment, protection of flood plains, creating public awareness and such other measures for promoting environmentally sustainable river conservation.

- Collection, analysis and dissemination of information relating to environmental pollution in the river Ganga.

- Investigations and research regarding problems of environmental pollution and conservation of the river Ganga.

- Creation of special purpose vehicles, as appropriate, for implementation of works vested with the Authority.

- Promotion of water conservation practices including recycling and reuse, rain water harvesting, and decentralised sewage treatment systems.

- Monitoring and review of the implementation of various programmes or activities taken up for prevention, control and abatement of pollution in the river Ganga, and

- Issuance of directions under section 5 of the Environment (Protection) Act 1986 (29 of 1986) for the purpose of exercising and performing all or any of the above functions and to take such other measures as the Authority deems necessary or expedient for achievement of its objectives.

- The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 for the purpose of exercising and performing these functions and for achievement of its objectives.

- The EPC model adopted in the earlier program for Ganga rejuvenation limited the contractor’s responsibility of running the plant for 2 years and after that, it was to be operated by the ULBs/Agencies concerned.

- To overcome the limitations a new concept of Hybrid Annuity Model (HAM) was introduced in the sewage sector for the first time making it a paradigm shift towards Nirmal Ganga.

- To work towards the sustainability of the infrastructure projects created, Namami Gange moved from just construction to construction plus performance approach by introducing HAM model wherein, 40% of capex was given by state and 60% of capex to be raised by concessionaire and the concessionaire will get the return in next 15 years in quarterly annually payments along with operation and maintenance.

- The model also ensures the timely completion of the construction of the plant as only a part is paid to them for the construction phase and any delay can lead to future loss.

- This has also improved the monitoring and operations of the plants like use of SCADA and other latest innovations.

- This is paradigm shift in sector wherein performance is inbuilt in model and value of investment is ensured.

- The HAM model then extended further by adopting a unique concept of ‘One City-One Operator’ to improve the governance and accountability in citywide waste water management.

- Wholesome approach of the mission comprising Aviralta, Nirmalta, ecological restoration and connecting people to the river. The focus of programme is slowly shifting to Aviralta, wherein, the right of river on its own water has been accepted for Ganga up to Kanpur barrage, e-flow has been notified and is being implemented for the first time for the Ganga main stem.