- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Mar 28, 2022

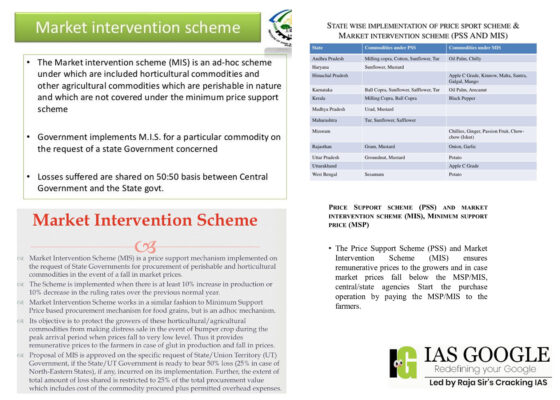

WHAT IS THE MARKET INTERVENTION SCHEME (MIS)? HOW DOES IT COMPARE WITH MSP?

Under the Market Intervention Scheme (MIS), Central Share of losses, if any, incurred in implementing MIS is released to the State procuring agencies as per the specific proposals received from the State Governments.

About Market Intervention Scheme

About Market Intervention Scheme

About National Dolphin Day

About National Dolphin Day

Genesis: Odisha is Shifting Towards Renewable Energy

Genesis: Odisha is Shifting Towards Renewable Energy

About Bucharest Nine

About Bucharest Nine

Oil Price Projections

Oil Price Projections

Key Findings

Key Findings

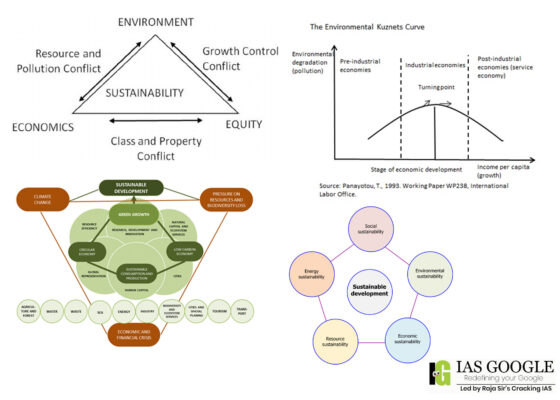

What is Environmental Conflict?

What is Environmental Conflict?

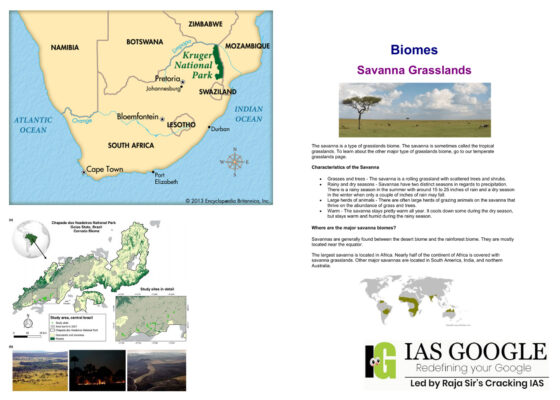

About Savanna Grasslands

About Savanna Grasslands

About The ‘Water Tower of Asia’

About The ‘Water Tower of Asia’

About Market Intervention Scheme

About Market Intervention Scheme

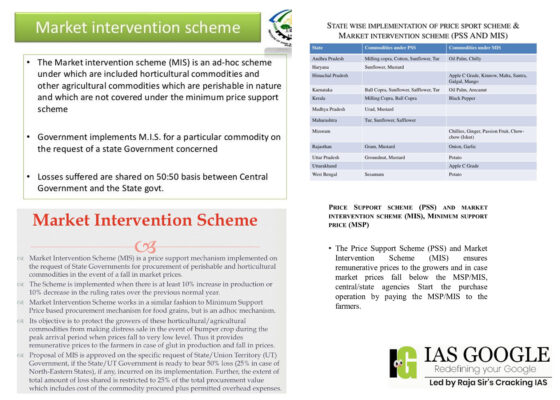

- Government implements Market Intervention Scheme (MIS) for procurement of agricultural and horticultural commodities which are perishable in nature and are not covered under the Price Support Scheme (PSS).

- The objective of intervention is to protect the growers of these commodities in the event of a bumper crop during the peak arrival period. The condition is that there should be either at least a 10 percent increase in production or a 10 percent decrease in the ruling market prices over the previous normal year.

- Under the scheme, in accordance with MIS guidelines, a pre-determined quantity at the fixed Market Intervention Price (MIP) is procured by the agencies designated by the State Government for a fixed period or till the prices are stabilized above the MIP whichever is earlier.

- The extent of total amount of loss to be shared on a 50:50 basis between the Central Government and the State Government is restricted to 25 percent of the total procurement value which includes cost of the commodity procured plus permitted overhead expenses.

- MIS has been implemented in case of commodities like apples, garlic, oranges, grapes, mushrooms, clove, black pepper, pineapple, ginger, red-chillies, coriander seed, chicory, onions, potatoes, cabbage, mustard seed, castor seed, copra, palm oil etc.

- MIS provides remunerative prices to the farmers in case of glut in production and fall in prices.

- Proposal of MIS is approved on the specific request of State/UT Government, if they are ready to bear 50% loss (25% in case of North-Eastern States), if any, incurred on its implementation.

- Further, the extent of total amount of loss shared is restricted to 25% of the total procurement value which includes cost of the commodity procured plus permitted overhead expenses.

- The Department of Agriculture & Cooperation is implementing the scheme.

- Under the MIS, a pre-determined quantity at a fixed MIP is procured by NAFED as the Central agency.

- There are other agencies designated by the state government for a fixed period or till the prices are stabilized above the MIP whichever is earlier.

- The area of operation is restricted to the state concerned only.

- Under MIS, funds are not allocated to the States.

- Instead, a central share of losses as per the guidelines of MIS is released to the State Governments/UTs, for which MIS has been approved, based on specific proposals received from them.

- The fundamental goal of MIPs is to prevent farmers from encountering severe price deflation for their products created due to massive production.

- To ramp up the growth of agricultural producers and farmers’ income

- To create more jobs for growers and farmers and provide them with financial stability

- To escalate the employment volume at the taluk level

- Agricultural items' prices are dynamic in nature and thus subject to frequent changes. So, there is a need to safeguard the growers and farmers against the sub-par sales of farm products by offering them a base level price.

- This scheme comes into effect when there is at least a ten per cent increase in the rate of production or a 10 per cent decrease in the ruling rate range when contrasted with the previous year.

- The MIPS scheme covers Agri products that do not fall under other centrally sponsored schemes, Price support schemes, Minimum Support Prices. MIPS encompasses agricultural and horticultural products that are perishable and do not fall under any other scheme

- Under the MIS scheme, the agri-based items are procured at a fixed MIPS, i.e., Market Intervention Price by the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Ltd (aka NAFED).

- NAFED is registered under the Multi-State Co-operative Societies Act. It was set up to promote Cooperative marketing of agricultural produce to benefit the farmers.

- The primary role of NAFED is to ensure continual procurement of farm products till the prices surpass the MIPS.

- The implementation of MIPS is done as per the needs raised by the state government agencies via NAFED.

- What is the procedure of obtaining the MIPS scheme?

- The MIP scheme is typically obtained via NAFED and agencies having the approval of the State Governments. Along with FCI, NAFED, Jute Corporation of India Ltd. (JCI), Competition Commission of India (CCI), and State Trading Corporation of India Limited (STC) are also actively participating in MIPS as part of the centrally authorized platforms.

- At the state level, state warehousing corporations, state-level marketing boards, state cooperative marketing federation, and state food and civil supplies departments are allied departments for MIS operation.

- To obtain MIPS, it has to be registered either under NAFED or respective state governments.

- MIPS covers apple growers from Kashmir territory.

- Allows procurement of the apples directly from the growers and aggregators

- Projected profit is accounted for Rs 2000 crores for the growers.

- Government agencies take charge of apple procurement and transportation, i.e. no expenses for farmers whatsoever,

- The present worth of the scheme is Rs 8000 crores.

- Ensures Seamless enrolment process, collection of bank account details, and payment to beneficiaries owing to the involvement of the district administration.

- Other Steps Taken by the Government to provide Farmers Remunerative Prices for their Produce, the Government has taken several steps.

- The Government has implemented National Agriculture Market (e-NAM) scheme an online virtual trading platform to provide farmers and Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) with opportunity for transparent price discovery for remunerative prices for their produce through competitive online bidding system.

- Through Agriculture Marketing Infrastructure (AMI) Scheme development of private mandis, direct marketing, declaring warehouses, silos, cold storages as deemed markets and also developing Gramin Haats into Gramin Agricultural Markets (GrAMs), are promoted.

- The Government is now implementing a central Sector scheme namely “Formation and Promotion of 10,000 Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs)” to enhance cost effective production and higher net incomes to the member farmer producers through better liquidity and market linkages for their produce and become sustainable through collective action.

- In addition to above, to provide additional channels to farmers for marketing of their produce and promote barrier-free inter-state and intra-state trade and commerce, the Government has promulgated “The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Ordinance, 2020” on 5th June, 2020. Now, farmers can sell their produce from their farm-gate, residence to processing units, warehouse, silos, cold storage etc. nearer to their farm-gate. Farmers are getting better prices, and also are able to save the transportation costs, unofficial payment of market fees, commission charges and other marketing charges in the existing system of agricultural marketing.

- The Market Intervention Price Scheme came as a relief for farmers who often have trouble securing good pay for their produce, particularly during the peak period. There are significant numbers of farmers in India who face the same issue throughout the year. The advent of this scheme shall provide them with a good profit margin for their crops.

- The Price Support Scheme (PSS) is being implemented by the Government of India in the state.

- Main crops of the state like Bajra, Jowar, Maize, Paddy, Cotton, Tur, Moong, Urad, Groundnut, Sesamum Wheat, Gram, Mustard, and Sugarcane etc. are covered.

- The Department of Agriculture & Cooperation implements the PSS for procurement of oil seeds, pulses and cotton, through NAFED which is the Central nodal agency, at the MSP declared by the government.

- NAFED undertakes procurement as and when prices fall below the MSP. Procurement under PSS is continued till prices stabilize at or above the MSP.

- Eligibility: Farmers of the State

- When prices of commodities fall below the MSP, State and central notified procurement nodal agencies purchase commodities directly from the farmers at MSP, Under specified FAQ (Fair Average Quality).

- By this way prices of the main commodities are procured and protect the farmers against the economic loss in farming.

- Farmers benefit from the scheme by selling their produce at a support price in APMC centers opened by Nodal procurement agency.

- Minimum Support Price (MSP)

- Is market intervention by the GoI to insure agricultural producers against any sharp fall in farm prices?

- Announced at the beginning of the sowing season for certain crops

- MSP on the basis of the recommendations of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP).

- MSP is price fixed to protect the producer – farmers – against excessive fall in price during bumper production years.

- The minimum support prices are a guarantee price for their produce from the Government.

- Methods of calculation

- In formulating the level of MSP and other non-price measures, the CACP takes into account a comprehensive view of the entire structure of the economy of a particular commodity or group of commodities.

- The CACP makes use of both micro-level data and aggregates at the level of district, state and the country.

- Other factors include cost of production, changes in input prices, input-output price parity, trends in market prices, demand and supply, inter-crop price parity, effect on industrial cost structure, effect on cost of living, effect on general price level, international price situation, parity between prices paid, prices received by the farmers and effect on issue prices and implications for subsidy.

About National Dolphin Day

About National Dolphin Day

- Considering that generating awareness amongst the people on the benefits of conservation of Dolphins is important, the Standing Committee recommended that every year 5th of October should be celebrated as National Dolphin Day.

- Healthy aquatic ecosystems help in maintaining the overall health of the planet. Dolphins act as ideal ecological indicators of a healthy aquatic ecosystem and conservation of the Dolphins will benefit the survival of the species and people dependent on the aquatic system for their livelihood.

- October 5 is currently celebrated as 'Ganga River Dolphin Day', but its re-designation now as a national day for this aquatic animal will encompass all rivers and oceans' Dolphins beyond the Gangetic ones.

- Bihar has already been celebrating October 5 as 'Dolphin Day' for the past several years.

- Generating awareness and community participation is integral for conservation of this indicator species.

- The Ganges River dolphin was officially discovered in 1801. Ganges river dolphins once lived in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna and Karnaphuli-Sangu River systems of Nepal, India, and Bangladesh. But the species is extinct from most of its early distribution ranges.

- The Ganges River dolphin can only live in freshwater and is essentially blind. They hunt by emitting ultrasonic sounds, which bounces off of fish and other prey, enabling them to “see” an image in their mind. They are frequently found alone or in small groups, and generally a mother and calf travel together.

- The Gangetic dolphin is an indicator species, whose status provides information on the overall condition of the ecosystem and of other species in that ecosystem, for the Ganga ecosystem and is extremely vulnerable to changes in water quality and flow. It is categorised as endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List.

- A WWF-India and the Uttar Pradesh Forest department assessment in 2012 and 2015 recorded 1,272 dolphins in the Ganga, Yamuna, Chambal, Ken, Betwa, Son, Sharda, Geruwa, Gahagra, Gandak and Rapti.

- It is also known by the name susu (popular name) or "Sisu" (Assamese language) and shushuk (Bengali).

- In the First Schedule of the Indian Wildlife (Protection), Act 1972.

- Endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

- Appendix I (most endangered) of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

- Appendix II (migratory species that need conservation and management or would significantly benefit from international co-operation) of the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS).

- The Indus River dolphin (Platanista minor), also known as the bhulan in Urdu and Sindhi, is a species of toothed whale in the family Platanistidae. It is endemic to the Indus River basin of India and Pakistan.

- This dolphin was the first discovered side-swimming cetacean. It is patchily distributed in five small, sub-populations that are separated by irrigation barrages.

- From the 1970s until 1998, the Ganges River dolphin (Platanista gangetica) and the Indus dolphin were regarded as separate species; however, in 1998, their classification was changed from two separate species to subspecies of a single species.

- However, more recent studies support them being distinct species. It has been named as the national mammal of Pakistan, and the state aquatic animal of Punjab, India.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered.

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES): Appendix I

- Indian Wildlife (Protection), Act 1972: Schedule I

- Habitat loss /Degradation / Disturbances – Annual flood, etc.

- Changing River course.

- Inland waterways / Movement of large cargo vessels.

- Various anthropogenic / religious activities.

- Excessive harvesting/hunting/food – subsistence use/ local trade.

- Directed killing/ poaching.

- Accidental killing – by catch/ fisheries related entanglements.

- Accidental mortality – others.

- Water pollution – Agriculture related – on both the banks of River/chemical.

- Water pollution – domestic / direct disposal of sewage / non-functional treatment plants.

- Pollution – affecting habitat and/ or species, Industrial effluents.

- Several major infrastructure projects within its region will impose a real risk for catastrophic population decline in the future.

- The absence of a coordinated conservation plan, lack of awareness and continuing anthropogenic pressure, are posing incessant threats to the existing dolphin population.

- Gangetic river dolphins were declared national aquatic species in 2010.

- The government, through the National Water Development Agency (NWDA) and Jal Shakti ministry, has started a programme of interlink rivers. NWDA has identified 30 such linking projects. The government has prepared detailed project reports for the Ken-Betwa link, the Daman Ganga-Pinjal link, and the Par-Tapi-Narmada link.

- The ‘My Ganga, My Dolphin’ campaign that is being rolled along with the census aims to build awareness and garner the support from local community members to volunteer as ‘Dolphin Mitras’ and to reduce the threats to the Dolphin population and sustain conservation efforts of the national aquatic animal.

- The survey team also will sensitise the local communities on the importance of Dolphins and the actions needed to conserve the habitat and species. There will be a communications and outreach strategy to disseminate the message of Dolphin conservation via print, electronic and social media.

- National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) in its efforts of biodiversity conservation in Ganga River basin has been working further on the Ganges River Dolphin Conservation Action Plan and has taken steps to coordinate with various institutions to:

- build capacity for Ganga River Dolphin Conservation and Management;

- minimize fisheries interface and incidental capture of Ganga River

- Dolphins;

- restore river dolphin habitats by minimizing and mitigating the impacts of

- developmental projects;

- involve communities and stakeholders for sustainable efforts in Ganga River

- Dolphin conservation;

- educate and create awareness and set off targeted research.

- Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary is located in Bhagalpur District of Bihar, India. The sanctuary is 60 kilometers stretch of the Ganges River from Sultanganj to Kahalgaon in Bhagalpur district.

- Notified as Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary in 1991, it is the protected area for the endangered Gangetic dolphins in Asia. Once found in abundance, only a few hundred remain, of which half are found here.

- The Gangetic Dolphin have been declared as the national aquatic animal of India.[1] This decision was taken in the first meeting of the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA) chaired by Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh on Monday, 5 October 2009.

- The Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary (VGDS) has been notified for the protection and conservation of Gangetic dolphin in the 60 km stretch of the Ganga River from Sultanganj to Kahalgaon under the provisions of Wildlife (Protection), Act 1972.

- Being a riverine habitat, its boundary and expanse keep on changing due to changing geomorphology of the Ganga River. The sanctuary has been named after the famous archaeological remains of Vikramshila University that was once a famous center of Buddhist learning across the world along with Nalanda during the Pala dynasty.

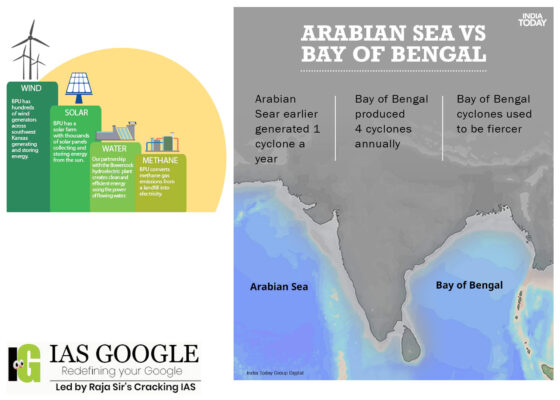

Genesis: Odisha is Shifting Towards Renewable Energy

Genesis: Odisha is Shifting Towards Renewable Energy

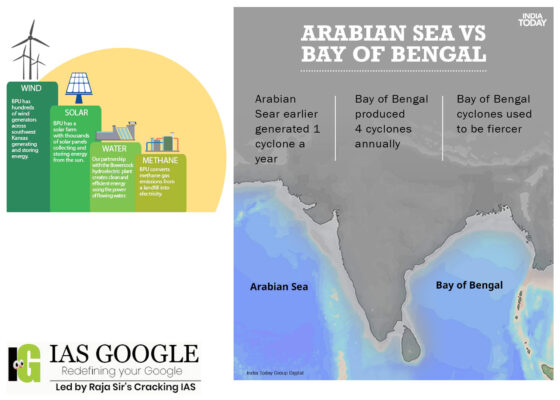

- Odisha, like its neighbours Andhra Pradesh and West Bengal, has seen some of the worst ever cyclones in India’s history. Between 1891 and 2018, the state was hit by about 110 cyclones.

- Well-documented evidence shows that many cyclones turn and steer in the Bay of Bengal to make Odisha a common landfall destination.

- That’s only likely to get worse as climate change increases sea surface temperatures and triggers more intense tropical cyclones.

- According to the 2013 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), fewer tropical cyclones will form as the climate gets warmer, but a higher fraction of these will be intense and cause more damage.

- The report also points to the higher likelihood of enhanced summer monsoon precipitation and increased rainfall extremes of landfall cyclones on the coasts of the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea. This will be unwelcome news to residents of the state whose lives are already plagued by extreme weather conditions such as thunderstorms, heat waves, floods and droughts.

- The demand for rooftop solar photovoltaic (PV) panels and other solar-powered appliances has risen in Odisha during recent years as people seek to meet emergency needs during disasters and to reduce their electricity bills.

- In 2019, when the severe cyclonic storm Fani made landfall near Puri, a coastal district in Odisha, it forced people to live without electricity over 15 days, including in Bhubaneswar.

- It had happened before, during the 1999 Super Cyclone. Electricity poles fell everywhere both times.

- The difference was that those who had installed rooftop solar panels by 2019, did not have to suffer.

- The Bay of Bengal is a core area of cyclone formation for this location – most cyclones that hit the region are formed here and many of them make landfall. Of the 36 deadliest tropical cyclones in the world, 27 have arisen to India’s East.

- Wind patterns in the Arabian Sea to India’s West keep oceans cooler, resulting in fewer storms. On the eastern coast, however, storms are more intense and a flatter topography that is unable to deflect the winds allows them to move easily landwards.

- The super cyclone of 1999, the strongest ever to hit India, killed more than 10,000 people after landfall in Odisha and unleashed such devastation that took years for the state to come back to normal. In recent memory, cyclone Phailin (2013) also caused massive damage to the state.

- Geographically, the landmass between Puri to Bhadrak on the map of Odisha juts out a little into the sea, making it vulnerable to any cyclonic activity in the Bay of Bengal.

- Even though some other cyclones – Hudhud (2014) and Titli (2018) – did not make landfall in Odisha, they caused severe damage to coastal towns. “It’s almost like one cyclone every other year now.”

- In the last few years, the demand for rooftop solar panels has increased 40 per cent.

- Solar-powered appliances have now come to even hard-to-reach villages of Odisha. Many people in such villages now have solar-powered lights, mostly with help from non-profit organisations. Like the Juangs. The Juangs, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group, live in the dense forests of Keonjhar district.

- Solar cooking stoves have helped women reduce their cooking hours.

- People are earning money by using cooking stoves to sell carbon credits.

- Odisha government had also invited Rescos (Renewable Energy Services Companies) to install rooftop solar PV systems in government buildings to both meet emergency demand and reduce carbon emissions.

- Electricity bills had become almost nil after investing a good amount in rooftop solar installation.

- In 2015, a mini solar plant was established and power supplied to every household. The village of 60-odd households became Odisha’s first 100 per cent solar village.

- This changed the life of villagers. The children got light to study, women could work till late evenings and spend time with themselves and men were returning home late. There was no fear of wild animals, reptiles and elephant attacks.

- Odisha plans to install 1,000-megawatt (MW) rooftop PVs by this year. But there are many challenges in both cities and villages.

- The government provides a 40 per cent subsidy to install residential rooftop solar systems. But in most cases, people have not received it yet.

- Lack of consumer awareness, difficulty in processing and timely approval of net metering applications and more recently, an increase of goods and services tax (GST) percentage on solar panels are among the problems.

- The increase in GST on solar panels from 5 to 12 per cent has had a negative impact on demand.

- Odisha Renewable Energy Development Agency (OREDA), a nodal agency of the Government of Odisha, said though demand had increased, apartments had space constraints when it came to installing rooftop solar panels.

- A new policy had to be implemented to install virtual net metering to meet this demand in future. A residential society would then be able to buy a plot in a far-off place and install solar panels and offset its bills.

- Many people are withdrawing from the idea because the initial investment is quite high.

- There are issues of maintenance of solar appliances in Odisha’s remote villages. Barapitha, a village of indigenous Santhal and Ho communities just 15 km from Bhubaneswar, was Odisha’s first solar model village.

- The plant broke down when Cyclone Fani struck. “Everything was destroyed — solar panels, batteries and invertors. People didn’t know how to repair; they were not trained and they had no idea whom to contact to repair it.

- The ministry is completely silent about what will happen to the asset after five years. It should bring a policy on this to extend the services of the assets.

- The biggest challenge in renewable energy is to ensure quality and maintenance service.

- There are similar stories elsewhere. When we realised, we had entered essential services, we felt it is necessary to provide maintenance to fulfill our objective. Thus, the first of its kind IT-enabled monitoring and service provider mechanism RESolve took shape.

- OREDA Stakeholders Engagement and Assets Management System (OSEAMS) is an IT- enabled monitoring mechanism through which stakeholders are engaged and their individual performances are monitored to achieve the goal is sustained on RESolve.

- If we want to continue with international commitment, we must make sure our assets are working for the period they designed for. In RESolve, the registered RE assets are being provided with services.

- In addition, a team will empower the community and get feedback from them. All private and individual RE assets need to be registered so that the state will have detailed data on all assets and their working conditions.

- Till now, nearly 80,000 RE assets have been registered on this platform.

- Presently, registered beneficiaries from any corner of the state can get their equipment serviced by dialing a toll-free number. But maintenance services are provided only for five years, though the lifespan of a RE asset is 15-20 years.

- As Odisha is disaster-prone, there should be a disaster plan before installation of RE assets. Some additional costs should be kept in Capex (capital expenditure) for disaster planning and mitigation; that will help in disaster response.

- Odisha has been able to protect its people. That's the most important part. In terms of bringing down the number of lives lost and the people getting affected, the state has done well. This has never happened in one day. Odisha took a conscious decision and gradually built upon its capacity, particularly at the community level.

- It has successfully started community-level warning, built multi-purpose cyclone shelters under National Cyclone Risk Mitigation Project and built an Early Warning Dissemination System with last-mile connectivity and now the role of renewable energy is also going to be started which will harness its model at higher reaches.

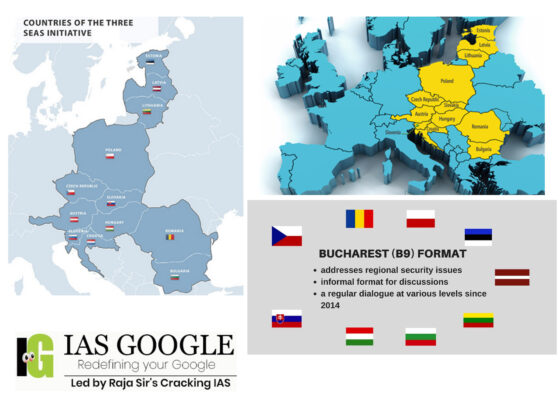

About Bucharest Nine

About Bucharest Nine

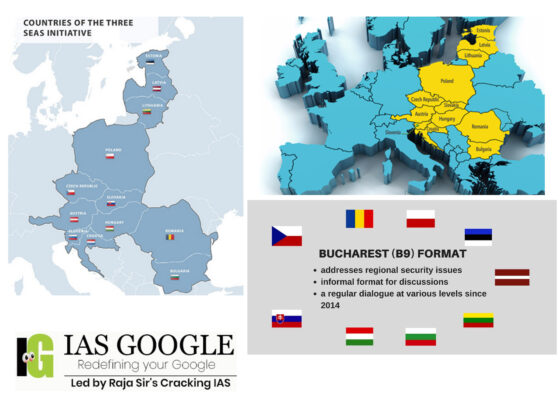

- The Bucharest Nine or Bucharest Format, often abbreviated as the B9, was founded on November 4, 2015, and takes its name from Bucharest, the capital of Romania.

- The group was created on the initiative of Klaus Iohannis, who has been President of Romania since 2014, and Andrzej Duda, who became President of Poland in August 2015, at the High-Level Meeting of the States from Central and Eastern Europe in Bucharest.

- The “Bucharest Nine” is a group of nine NATO countries in Eastern Europe that became part of the US-led military alliance after the end of the Cold War.

- According to a 2018 release from the office of the Romanian President, “the Bucharest Format (B9) offers a platform for deepening the dialogue and consultation among the participant allied states, in order to articulate their specific contribution to the ongoing processes across the North-Atlantic Alliance, in total compliance with the principles of solidarity and indivisibility of the security of the NATO Member States.”

- The B9 are, apart from Romania and Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and the three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All nine countries were once closely associated with the now dissolved Soviet Union, but later chose the path of democracy.

- Romania, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria are former signatories of the now dissolved Warsaw Pact military alliance led by the Soviet Union. (The other Warsaw Pact countries were the erstwhile Czechoslovakia and East Germany, and Albania.) Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were part of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).

- All members of the B9 are part of the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO).

- Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014. B9 was formed condemning the annexation. The B9 members were either a part of the Soviet Union before its disintegration or a sphere of influence. The B9 has proposed to extend the organisation eastward. It wants to include Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia. Ukraine is of great importance to US, EU and B9 because it is the buffer between the western world and Russia.

- The Sea of Azov and Black Sea are connected by the Kerch Strait. The Kerch strait is located in Crimea. The strait is an important sea route. Russia can reach Mediterranean countries through this strait. Russia annexed Crime for its strategic location. Crimea was a part of Ukraine. The US and EU are against this annexation. Reason: They do not want Russia to capture the Mediterranean market.

- Content analysis of the statements, documents, and steps by B9 leaders signals that B9 countries are aware of stronger European and Euro-Atlantic solidarity, cooperation with the US, increased defence spending and justified necessity to provide comprehensive support to Ukraine as the key predicaments for ensuring stability, security, and development in the region.

- In this favourable context, Ukraine should intensify relations with CEE countries within B9 and open a window of additional opportunities for setting up B9+. This is of special interest in the situation where Ukraine is in the status of a partner-state rather than a NATO member-state.

- Therefore, Ukraine is in a position to initiate formalised mutual assistance and solidarity with B9 in countering Russia’s military expansion. This would help boost the current B9 format into a full-fledged B9+Ukraine or B10.

- Supported by Ukraine’s allies, primarily the US, this format would decrease risks in designing solidarity approaches to the policy of deterring Russia and guarantee security and defence resilience of countries in NATO’s eastern flank.

- Ukraine should focus on the following areas to accomplish these goals:

- It seems advisable to start regular Conferences of Defence Ministers of B9+Ukraine to share information, shape a joint vision and joint responses on the security challenges provoked by Russia in the region;

- Based on the available solidarity and mutual understanding among B9 states and Ukraine, to invest diplomatic and political efforts into forming a B9 countries club of support for Ukraine joining NATO. With this, Kyiv has a chance to strengthen the loyalty of Washington and weaken the scepticism of Berlin in this matter;

- To initiate the involvement of military specialists from B9 states to support the Armed Forces of Ukraine in overcoming the existing gaps and strengthening the Ukrainian Army capabilities. Ukraine can initiate sending more advisors of B9 countries to work at NATO Representation to Ukraine and for some advisory initiatives;

- To contribute to shaping a security identity within B9 that would reflect the understanding of own responsibility for supporting stability and ensuring regional security, and recognising the need to expand NATO’s responsibility zone beyond its borders to the countries that share the values of a free and the rule of law society and comply with the criteria of the democratic world while also facing unjustified aggression from third parties;

- A joint summit of the Visegrad Four and the Lublin Triangle with other NATO member-states, including Turkey and the EU, could catalyse the shaping of B9+. It is also possible to consider inviting Georgia to such a summit;

- The B9 and Ukrainian expert community should initiate a B9+ Expert Forum that could provide analytical support in evaluating regional threats, the prospects of Ukraine’s integration with NATO, and efforts to increase compatibility and shape the joint strategic vision of cooperation

- The B9 countries have been critical of President Vladimir Putin’s aggression against Ukraine since 2014, when the war in the Donbas started and Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula.

- The envoys rejected the Russian claim (which has been amplified by the Chinese) about the eastward “expansion” of NATO, and “underlined that NATO is not an organisation that “expanded” to the east”, rather, “It was we, the independent European states, that decided on our own to go west.”

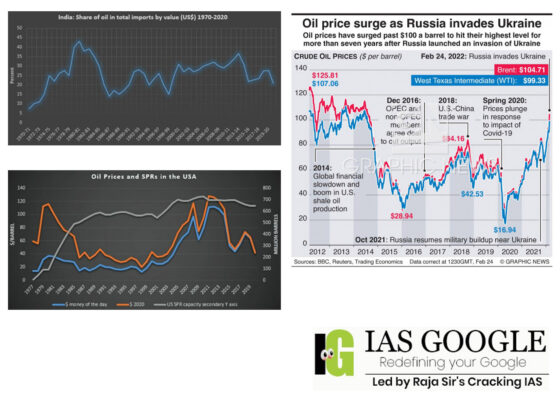

Oil Price Projections

Oil Price Projections

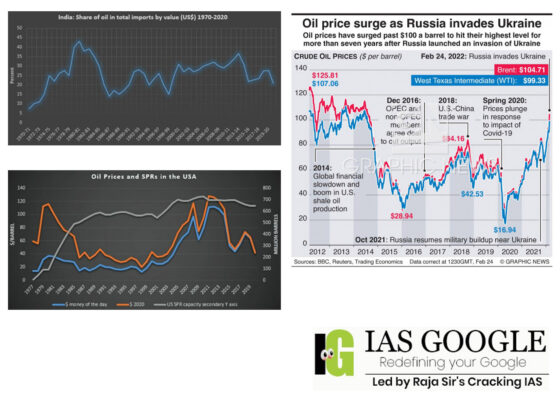

- Following the crisis in Ukraine, self-sanctions against Russian oil by oil traders concerned about payment bottlenecks along with Russian oil import sanctions by Western economies increased the price of Brent crude.

- Growth in oil supply that exceeded growth in demand and inventory increases were expected to exert a downward pressure on oil prices.

- Production of crude was expected to increase by 5.5 million barrels per day in 2022 with the USA, Russia, and the OPEC (Oil Producing and Exporting Countries) accounting for 84 percent of the increase.

- The forecast was made prior to the import bans on the Russian crude by the USA and other European countries which leaves the possibility of another upward revision open.

- Genesis:

- Two factors contributed to India’s 1991 balance of payments crisis. One was the crisis in the Middle East and the consequent increase in oil prices which battered the current account. The second was the economic slow-down in India’s trading partners which added to the current account crisis.

- In 1991, the value of petroleum imports increased by US$2 billion to US$5.7 billion as a result of an increase in oil prices combined with an increase in the volume of oil imports. In comparison, non-oil imports increased only by 5 percent in value terms and 1 percent in volume terms.

- The rise in oil imports led to a sharp deterioration of the trade account which was already under pressure on account of the fall of the erstwhile Soviet Union which was India’s important trading partner. The rest was history.

- The share of crude in India’s total imports (in terms of value) has fluctuated in the last four decades reflecting changes in the global and domestic economy. In 1970, it was less than 10 percent but increased to more than 40 percent during the oil crises of the late 1970s.

- It has remained above 25 percent over the last two decades. Though this partly reflects an increase in consumption of oil, it also reflects higher oil prices (interrupted by the financial crisis in 2008 and the pandemic in 2019).

- In fact, during the pandemic, the narrative on oil prices centred around the theme “lower for longer”. In 2022, sanctions and uncertainty in the oil market appear to have changed the narrative to “higher for longer”. However, there is no certainty over this either.

- India is particularly vulnerable to higher oil prices because we import over 84% of all our oil needs.

- If domestic prices were to be brought in line with the global spike, then, a litre of petrol and diesel would go up by Rs 25 and Rs 35, respectively, and a cylinder of LPG would be costlier by around Rs 400.

- Similarly, coal prices go up, making electricity costlier. Natural gas prices also go up and so do the prices of fertilisers since they use gas as the feedstock and gas accounts for 80% of all fertiliser production costs.

- Costlier oil and other related commodities could imply an additional import burden of $100 billion on the economy in the coming 12 months. That’s roughly Rs 7.7 lakh crore (around 10 years of MGNREGA budget allocation) that Indians would have to spend more just to maintain consumption levels.

- Regardless of who pays the money — whether the government passes through the higher prices on to the consumers or shields them completely by increasing subsidies — such an increase in the import bill will knock down the aggregate demand in the economy. That, in turn, will hurt India’s overall growth.

- Oil prices impact the Indian economy through various channels. In the short term, high crude prices could increase inflation if the increase in crude prices are passed through to the retail consumers.

- At the extreme, inflation estimate of 4.5% for 2022-23 by the RBI (Reserve Bank of India) could increase by about 1% if oil prices remain at about US$100/b.

- The impact could be lower if oil price pass through is curtailed by reducing taxes on petrol and diesel, but this will translate into an increase of India’s fiscal deficit.

- India’s current account deficit (CAD) could increase significantly if oil prices remain high for a longer period. Oil is a critical input to the Indian economy and in the short term, demand is inelastic to price which means that when oil price increases, the oil import bill increases proportionally.

- In 2020-21, oil accounted for over 20 percent of India’s total import bill. Oil imports alone contributed about 56 percent of the total trade deficit of over US$102 billion.

- Analysis of the past oil price shocks suggest that the nature of the oil shock matters in understanding the effects of oil price shocks. Oil shocks can be aggregate demand driven, oil-specific demand driven, or supply driven as in the current case.

- Supply-driven oil shocks contribute more to the increase in current account imbalances than demand-driven shocks, and the impacts of supply-driven shocks are closely related to the degree of energy dependence.

- In a demand-driven oil shock, the impact on current account imbalance is weak because an increase in oil price comes from an increase in global economic activity.

- The conclusion is that the trade channel (rather than the asset valuation or exchange rate channels) represents the main adjustment mechanism to oil shocks. Increasing exports under current circumstances of geo-political turmoil, high commodity prices, and supply chain bottlenecks will be challenging for India.

- Higher growth rate of GDP (gross domestic product), even if achieved, will not necessarily cushion the adverse effect of high oil prices. It is estimated that even a 1 percent increase in GDP growth rates will not change the ratio of CAD to GDP significantly.

- In the longer term, sustained increase in oil prices could have an impact on economic activity and output. Decrease in the productivity of the economy because of an increase in the cost of production could also negatively impact wages, employment, and eventually the purchasing power of households.

- Analysis of the correlation between oil price shocks and macroeconomic outcomes show only a weak correlation between oil price shock and economic output for India compared to other large oil importers.

- The possible explanation is that India’s industrial output is more dependent on domestic coal, but this cannot lead to complacency. In most of the past supply-driven oil shocks, India’s economy has slumped along with the rest of the world.

- The consumption of food and fuel is very “inelastic” — that is, it does not change much when prices change. What’s worse, this inelasticity is higher for poorer consumers — the same lot of millions of people who have been struggling to recover their income and consumption levels, the so-called labharthis in political lingo — and as such, they would be worst affected by the resultant inflation.

- If the government chooses to save consumers and decides to pay the extra cost from its coffers then one of two things will happen: Either its fiscal deficit will go up or it will have to restrict capital expenditure.

- The Fiscal deficit essentially refers to the amount of money the government has to borrow from the market to plug the gap between its total expenses and its total revenues. Higher levels of fiscal deficit (borrowings) typically result in fewer loanable funds being available in the market for the private sector to get a new loan (e.g., to start a new business).

- If the government decides that it will both save the consumers as well as meet its fiscal deficit target then it will have to restrict its spending on capital expenditure. But ramping up capital expenditure has been the central strategy adopted by this government to boost growth and create jobs.

- Cutting back on capital expenditure in 2022-23 would derail the government’s medium-term growth strategy. It is also important to note in this regard that the financial year after that (i.e., FY24 or 2023-24) will be a pre-election year and there is a good chance that the government may want to keep some finances available for pre-poll freebies.

- But demand destruction is not the only way higher oil prices will impact the Indian economy. That is just the first-order effect.

- If the oil prices stay high for longer than 3-4 months then the second-order effects will start to kick in. These will include events such as firms starting to fail — because demand for their goods has fallen — and as a result, the profitability of banks that gave loans to such faltering firms will come into question — because those firms will struggle to pay back the money, leading to those loans turning into non-performing assets (or NPAs).

- The second-order effect essentially captures what may happen to investments in the economy. The investments — or the money spent by private firms and governments to build new productive assets — is the second-biggest engine of GDP growth in India; it accounts for 33% of all GDP.

- But faltering demand as consumers struggle with higher inflation will remove the incentive among private sector firms and entrepreneurs to spend money and invest in scaling up capacities.

- While it is true that a lot of corporate firms have much healthier balance sheets today than 2-3 years ago, that per se is only the necessary condition for boosting private sector investments. The sufficient condition is for the economy to have durable demand.

- In the absence of robust and widespread demand, the government’s Budget strategy of a private sector investment-led growth can, and will, unravel.

- If oil prices remain higher for longer, it leads to demand destruction through an increase in efficiency of end use and a shift to alternatives that brings prices down. But this takes time.

- The share of fossil fuels in the global primary energy basket fell from over 95 percent in 1965 to about 84 percent in 2020. The share of oil in the global primary energy basket fell from over 41 percent to 34 percent in the same period but the geo-politics around oil appears to have held its ground.

- In 1956 the USA used its financial and military dominance to stop Anglo–French military action against nationalisation of the Suez Canal by Egypt. Oil tankers were prevented from using the Suez Canal through which 1.2 million barrels of crude was carried each day. A major pipeline carrying half a million barrels of crude from Iraq through Syria was also sabotaged and exports of Middle Eastern oil to Britain and France were blocked.

- Surprised at their NATO (North Atlantic Treaty organisation) ally’s betrayal, several European countries turned to oil from the Soviet Union and in the 1970s gas from the Soviet Union. The irony to be noted by oil importers today is that more than 60 years later, oil’s strategic significance and oil importers’ (Europe’s) vulnerability has endured though the roles of the perpetrator and saviour have reversed.

- Typically, central banks should not react to supply-side shocks. But when such shocks lead to persistent inflation, which, in turn, leads to higher inflation expectations among the people, then the central bank should intervene.

- The problem, is that the RBI has been “significantly underestimating” inflation risks in India. Given this background, RBI will do one of two things: Either it will be forced to resort to a sharp course correction in the coming months or it will continue to accommodate higher inflation in its continuing bid to support higher growth.

- If it does the former, then, the repo rate — the interest rate that the RBI charges commercial banks when it lends money to them — to go up sharply from 4% at present to 5%. Since the repo rate is one of the most fundamental rates in the economy, this hike will raise the costs of borrowing across the board, thus hurting fresh investments.

- In case the RBI decides to see through higher inflation and solely bother about boosting GDP growth then it will risk India facing stagflation. That’s because higher inflation would continue to erode consumers’ purchasing power and overall demand. This, in turn, will bring down the returns on investment for private sector firms. The net result would be unrestrained inflation and stagnant growth — or stagflation.

- The net effect of the Covid pandemic on India is that the trajectory of India’s GDP growth has moderated while the trajectory of domestic inflation has spiked. Add to this the uneven — “K-shaped” — economic recovery. In such a situation, the oil price shock will further exacerbate all these recent trends.

- The only way out is for the Ukraine conflict to end within the next month or two. The Indian economy was poised to “take-off” just before the Ukraine crisis. As such, if the Ukraine crisis blows over in just three months, then India’s economic recovery will march on and the “outlook is very positive”.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- The nine targeted states — Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh and Assam — recorded a similar uptick during the period, ranging from 50-64 percentage points.

- Madhya Pradesh led the way with a 64.5 percentage point growth. These states account for nearly half of India’s population, over 60 per cent of maternal deaths, 70 per cent of infant deaths and 12 per cent of global maternal deaths.

- In 2020-21, nearly 17 per cent pregnant women received free medicines, 19 per cent received free diagnostics, 19 per cent received free food, 7 per cent received free transport (home to the facility and drop back) under this scheme, according to data from the Health Management Information System.

- The Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan, launched in June 2016, was aimed at providing free, assured and quality antenatal care. As of January 5, 2021, more than 20.6 million antenatal care check-ups were conducted by over 6,000 volunteers in over 17,000 government facilities.

- In the early 2000s, institutional deliveries were very low in India, mainly because access to the services was limited. With the launch of the National Health Mission and schemes like Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), the indicator has improved considerably.

- Institutional deliveries were first incentivised by the central government in 2005 with JSY, under which a direct cash transfer is promised if a woman delivered a baby at a medical facility, rather than at home. Annual JSY beneficiaries have shot up to over 10 million from 739,000 in 2005-06, according to the 2020-2021 annual report of the Union health ministry.

- Expenditure under the scheme has seen a similar trend, up from Rs 38 crore in financial year 2005-06 to Rs 1,773.88 crore in 2019-20. In 2020-21 (up to September 2020), the expenditure reported was Rs 703.64 crore (provisional), the report showed.

- The Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK), built on the success of JSY, was launched in June 2011. It entitled pregnant women to several benefits, including no-expense childbirth, free transport from home to medical facility, drugs, diet during stay, diagnostics and blood transfusion.

- In 2013, the cost of treating “complications during ante-natal and postnatal period and sick infants up to one year of age” was also brought within the ambit of the scheme.

- 91 per cent of the expectant mothers who visited a health facility at least four times during pregnancy went for institutional deliveries. In contrast, only 57 per cent of the women who did not visit the hospital during pregnancy opted for institutional deliveries.

- Institutional deliveries were also higher (95 per cent) in women who received at least 12 years of schooling, compared to women (62 per cent) who have not received any formal education.

- The driving force behind local women opting for institutional delivery has been the slew of government schemes that have incentivised it — either through conditional cash transfers or other benefits.

- Aligned with the goal of reducing maternal and child deaths through improved access to maternal health services, the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) was introduced in India in 2005.

- Crucial to the NRHM is the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) who is tasked with the role of mobilizing, counselling and supporting pregnant women in the community, particularly in relation to institutional delivery, antenatal care and postnatal care.

- Increasing awareness after the policy of branding schemes related to women’s institutional deliveries.

- Increasing literacy rate as well as awareness generation programmes among people in rural and urban areas led to growth of institutional deliveries.

- After the introduction of Pradhan Mantri Ayushman Yojana, the people could easily get access to secondary and tertiary hospitals for treatments and institutional deliveries.

- Development of Mohalla Clinics and taking steps in improving the conditions of Primary Health Care Centres led to growth of institutional deliveries.

- Maternal mortality ratio (MMR), infant mortality rate and neonatal mortality rate (NMR), however, have not improved at the same pace as institutional births. The nine focus states continue to have the highest MMR, a majority of which are well beyond India’s national average of 103 e.g., Bihar — 130; UP — 167; MP — 163; Assam — 205.

- Healthcare delivery and service utilisation are very different in two groups of India’s states — those performing better than the national average and those lagging behind. The country as a whole may be able to meet the United Nations-mandated Sustainable Development Goal of reducing MMR to 70 by 2030, but the lagging states will continue to perform poorly unless given an impetus.

- Except Assam, the states recorded a higher NMR in private institutions than home births. The five other focus states recorded a difference of under 17 deaths per 1,000 births.

- Despite the increase in delivery facilities, neonatal and infant mortality rates remain high.

- Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) and Auxiliary nurse midwives are the backbone of the government schemes but are severely burdened.

- Some schemes are applicable only if the mother is 19 years of age or above, some are only for the first child and some require ‘below poverty line’ identification. An 18-year-old pregnant woman living below the poverty line is most vulnerable but would not make the cut for several schemes.

- Teenage pregnancy poses a higher risk to the life of both mother and foetus. Teens, who are yet to attain adequate physical, mental and emotional development, are at an increased risk of developing high blood pressure and anaemia during pregnancy. More often than not they deliver before term and their babies have low birth weight.

- The local women give birth at hospitals but rarely seek care through their pregnancy. Of the 28 women in the ward, only one went for three antenatal care (ANC) check-ups during her pregnancy, while others went for either two or none.

- Every PHC and CHC has a staff shortage, some are running on half the strength required while others don’t have any nurses at all.

- Lack of expertise is an issue that has been plaguing us for a very long time. Institutional births are on the rise but there is a desperate need to reorient the staff so that they are well trained to handle complex cases.

- Janani Suraksha Yojana: Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) is a 100% centrally sponsored scheme which is being implemented with the objective of reducing maternal and infant mortality by promoting institutional delivery among pregnant women.

- Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA): It has been launched to focus on conducting special AnteNatal Check-ups (ANC) checkup on 9th of every month with the help of medical officers to detect and treat cases of anaemia.

- Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY): It is a maternity benefit programme being implemented in all districts of the country with effect from 1st January, 2017.

- LaQshya Programme: LaQshya (Labor room Quality Improvement Initiative) intended to improve the quality of care in the labor room and maternity operation theatres in public health facilities.

- Poshan Abhiyaan: The goal of Poshan Abhiyaan is to achieve improvement in the nutritional status of Children (0-6 years) and Pregnant Women and Lactating Mothers in a time-bound manner.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) mandates at least four ANC check-ups for early detection of anaemic cases, congenital anomalies, prevent low iron levels and ensure proper nutrition of the mother and foetus.

- Incentive-driven schemes at a state-level that promote institutional births include Shramik Seva Prasuti Sahayata Yojana in Madhya Pradesh, Janani Suvidha Yojana in Haryana, Ayushmati Scheme in West Bengal, Chiranjeevi Yojana in Assam and Gujarat and Mamta Friendly Hospital Scheme in Delhi.

- The Union health ministry has proposed the mandatory opening of joint savings accounts for pregnant women enrolled under the scheme after a ministry audit found several instances where information was forged to collect the cash incentive.

- Policies that recognise and monitor the subnational disparities, particularly in the Empowered Action Group States plus Assam, and the rural and tribal areas are needed.

- Schemes incentivising institutional delivery are not enough to ensure a safe birth. A holistic approach is needed to address infrastructure and human resource shortcomings.

- An infrastructure development plan focused on the actual patterns of use could close the remaining gaps in a very short time.

- The workforce involved in delivery of the various government schemes need to be strengthened to bring about a noticeable change.

- The eligibility criteria for such schemes needs to be expanded, because currently it excludes those who actually need it.

- An ideal institutional delivery needs to be defined for better monitoring of the scheme outcomes.

- We can have a 10-point checklist, with indicators such as how soon the pregnant woman is checked by the midwife, was the pulse / heartbeat of the baby recorded, proper steps of infection control and 5-6 immediate steps for baby’s survival.

- India must also close the data gap. Each institution must publish their morbidity and mortality data regularly.” Health centres must also be incentivised to deal with such a high load.

- Several studies have concluded that an increase in institutional delivery doesn’t guarantee a reduced MMR, raising “questions about the quality of care offered at facilities,” a 2014 paper published in Science argues.

- Institutional delivery service utilisation and avoiding births in homes in India is one of the key and proven intervention to improve maternal health and to reduce maternal mortality through provision safe delivery environment.

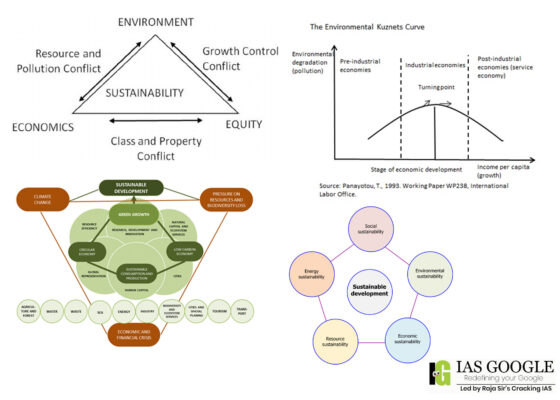

What is Environmental Conflict?

What is Environmental Conflict?

- Environmental conflicts can be broadly defined as social conflicts related to the environment. They differ, but frequently overlap, with other types of conflicts on gender, class, territory, or identity.

- Decreasing resource base and the struggle for control and power leads to politicising ecological issues and the eventual clash between different beneficiaries.

- Due to privatisation and the control of resources by the socially powerful, based on gender, class and ethnicity. Securing control of resources politicises ecological issues. This happens due to basic assumptions about the division of labour in society and access to the environment.

- Property rights, which are historically demonstrated to yield economic benefits when under private control, are a complex bundle of rights for everyday goods, which have to be shared among community members.

- Next is the problem of imagined identities by development planners and policymakers, which leads to conflict due to biases. Take the case of Thar in India for instance: Lack of access, opportunities, unfair distribution of work and the rewards accrued from the same leads to conflicts like gender wars and unionisation.

- Conservation efforts that change the ownership of resources also lead to social conflict. The rights over property are always complex due to sharing and differing ways of accessing it for income, inheritance and benefits. These have evolved after a long time due to landscape and temporal variation.

- Exclusive rights to use land led to conflicts, losses and inequality, and cutting off marginal users. Different investments by development planners and the non-congruence of various stakeholders also lead to divergence and possible clashes.

- The new immigrants had an unrealistic idea about the part of the country and imagined it to be free from human intervention. They were amenity-seeking newcomers who were in direct conflict with farmers and ranchers.

- The farmers depended on this very land for production. They viewed land as private property that could be bought and sold for consumption. It was traditionally developed to suit local farming needs and made sufficiently liquid to parcel in chunks.

- The new immigrants are consumers in the capitalist economy, who view the West as relief from the hectic urban life. The old inhabitants, who were producers of the economy, viewed land as a resource for farming and production.

- We get to experience gender discrimination and conflicts due to resource enclosure over time through a study in the far-off deserts of India, Thar. Here, the dispute arose after the state intervened in the local production system and land intensification.

- The green revolution was accelerating, leading to increased food production. Despite this increase, women still had disproportionately low access to food and nutrition and the wage-gap increased.

- Biodiversity conflicts: conflicts between people about wildlife or other aspects of biodiversity. This also includes conflicts relating to conservation of protected areas, green technologies as well as fair trade and patenting rights in relation to biodiversity and indigenous knowledge linked to natural resources. These conflicts can occur internationally and have serious regulatory and policy implications. Impacts on the natural resource base in terms of land clearing for development and agricultural production as well as the effects of genetically modified crops on biodiversity are important considerations as well.

- Coastal zone conflicts: Conflicts in coastal zones are interesting in that they could develop from a combination of other types of conflicts. This has to do with high development demands, high population density, environmental degradation and importantly, poor and disjointed management to balance conservation and development. There are two types of coastal zone conflicts – those related to ecosystem change and those related to coastal development.

- Conflicts disproportionately affecting women: Women are often vulnerable in the broader sense (physically, economically, socially and politically) and therefore often carry a disproportionate brunt of the effects of environmental conflicts and stress. The actual costs of environmental conflicts on women are multifaceted and hard to measure, women often experience greater food and economic insecurity, and are affected by unsafe or illegal practices.

- Conflicts about air quality and noxious pollutants: This is a key type of environmental conflict that relates to issues pertaining to social justice and the right to live in a healthy environment. Furthermore, an important theme is environmental racism and the links between poverty and vulnerability. While most conflicts relate to demonstrations and legal disputes as local residents and environmental activists mobilise communities to assert their rights, there are also incidences of violent conflicts.

- Land conflicts: The importance of land in conflicts relates to people’s ability to make a living or make a profit. Land scarcity or ambiguous property rights can contribute to grievances and violent conflict. This is particularly the case when alternative livelihoods are absent, and is often exacerbated when communities are armed. Population growth and movement, international markets, insecure property rights and legislation, climate change, environmental degradation and a myriad other factor all appear to be variables that need to be tracked in analysing conflicts where land plays a role. Finally, desertification, unsustainable use or drought can bring communities with competing livelihoods into further conflict.

- Water conflicts: Several countries rely on water sources from outside their boundaries. Local and international competition over water resources will increase. This is likely to have impacts on national security as well as threaten livelihoods at the local level. The water itself is not only a source of conflict, but the resources in the water bodies, specifically fish, are also points of contestation.

- Climate change and environmental conflicts: It is now widely recognised that climate change is having and will have significant impacts on social, economic and ecological systems and processes as socio-economic inequalities widen locally as well as globally. Climate change is increasingly being called a ‘security’ problem because there is concern that climate change may increase the risk of violent conflict.

- The women cultivators of Gambia are a good case in point. Access to land in the country was divided based on gender, like many African nations. Men managed dry uplands and women overlooked flooded plains.

- While planning is a prerequisite for effective management and implementation in any context, it often remains an ideal rather than a reality.

- Examining scientifically the interface between climate change models and conflict models including geographic variations, rates of change and adaptive measures.

- Considering and specifying what types of violence are likely to result from climate change. This will require conflict monitoring.

- Balancing the positive and negative effects of climate change as well as the effects of various strategies of adaptation.

- Continuing to disaggregate the effects of climate change in systematic conflict models (in relation to geographical variations and types of change) to ascertain differing outcomes.

- Focusing on national security issues in both developing and developed countries. The construction of security scenarios is also advocated.

- Environmental management and environmental protection should balance the needs and interests of the environment, the people and especially the vulnerable. Targeted, flexible, well-informed and contextual approaches to NRM and conflict resolution are necessary.

- This should go hand in hand with helping those dependent on the environment to develop independent capacity to withstand shocks resulting from environmental change.

- Planning and management of land activities should take into account environmental, social, political and other aspects.

- Post-conflict peacebuilding processes should take into account the effect a conflict had on the environment and the stresses on the environment and people in the post-conflict period.

- In post-conflict situations there is a need for a long-term vision for sustainable development to balance environmental and social objectives and in particular to address vulnerability, unemployment and population growth.

- Environmental conflicts take on different forms and have multiple and varying impacts in different contexts. In particular, key points of conflict are in relation to climate change, conservation, water quality and availability, air quality and management aspects. Furthermore, a disconcerting trend is the migration levels associated with environmental and other conflicts that often result in existing or new conflicts emerging in receiving areas.

- The matter of vulnerability remains an important aspect of understanding environmental conflicts. This issue highlights that the poor, marginalised groups and especially women are more likely to be impacted by environmental degradation and conflicts, whatever their types.

- Environmental conflicts and/or threats of conflicts are emerging as critical issues for security and conflict research. These types of conflict also influence political processes and pose unique challenges in relation to how they are managed, including how government structures anticipate points of stress and insecurity.

- The magnitude and diversity of environmental conflicts and related risks are complex and have significant implications for the stability of natural, social, political and economic contexts and locations. Thus, environmental conflicts can threaten nature and social security.

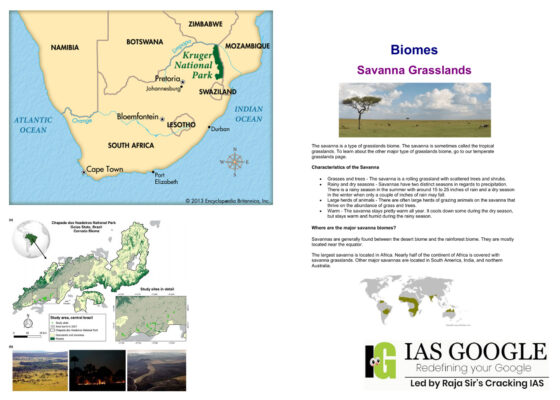

About Savanna Grasslands

About Savanna Grasslands

- A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to support an unbroken herbaceous layer consisting primarily of grasses.

- Savannas maintain an open canopy despite a high tree density. It is often believed that savannas feature widely spaced, scattered trees. However, in many savannas, tree densities are higher and trees are more regularly spaced than in forests.

- Savannas are found to the north and south of tropical rainforest biomes. The largest expanses of savanna are in Africa, where much of the central part of the continent, for example Kenya and Tanzania, consists of tropical grassland. Savanna grasslands can also be found in Brazil in South America.

- The African savanna ecosystem is a tropical grassland with warm temperatures year-round and with its highest seasonal rainfall in the summer. The savanna is characterized by grasses and small or dispersed trees that do not form a closed canopy, allowing sunlight to reach the ground.

- Savannas are also characterised by seasonal water availability, with the majority of rainfall confined to one season; they are associated with several types of biomes, and are frequently in a transitional zone between forest and desert or grassland. Savanna covers approximately 20% of the Earth's land area.

- The Savanna regions have two distinct seasons - a wet season and a dry season. There is very little rain in the dry season. In the wet season vegetation grows, including lush green grasses and wooded areas. As you move further away from the equator and its heavy rainfall, the grassland becomes drier and drier - particularly in the dry season. Savanna vegetation includes scrub, grasses and occasional trees, which grow near water holes, seasonal rivers or aquifers.

- Plants and animals have to adapt to the long dry periods. Many plants are xerophytic - for example, the acacia tree with its small, waxy leaves and thorns. Plants may also store water, for example the baobab tree) or have long roots that reach down to the water table. Animals may migrate great distances in search of food and water.

- The soil of tropical savannas is often poor, being low in nutrients, and either lacking water, or waterlogged, depending on the season.

- In the rainy season, soil becomes saturated and nutrients are pulled down from the topsoil, making it harder for plants to have access to them.

- In the dry season, there is very little water in topsoil, although the deeper soil does manage to retain some, and the dry dead vegetation causes many fires. These fires initially release nutrients to the soil, but they also burn away some of them in the form of smoke, and ashes are easily blown away by the wind.

- Low nutrients make nitrogen-fixing organisms, such as blue-green algae and certain bacteria, really important. Nitrogen-fixing organisms are able to take nitrogen from the air—atmospheric nitrogen—that is unusable to most plants, and turn it into usable nitrogen—nitrates—in the soil. Many of these nitrogen-fixing microbes are in a mutualistic symbiotic relationship with plants, where they help the plant get more nitrogen and the plant gives them carbon—it’s a win-win.

- A recent study examines the effect of different fire regimes in Kruger National Park, South Africa, which constitutes a tropical savanna ecosystem. Savannas are fire-dependent ecosystems where fire disturbance has played a key historical role in their evolution and maintenance.

- It is important to note the difference between ‘forest’ fires and savanna fires. ‘Forest fires,’ as the name suggests, occur largely in temperate and boreal forests and burn trees. On the other hand, savanna fires only burn herbaceous plants that are close to the ground and, therefore, might release less CO2 into the atmosphere.

- While a biome’s response to fire is largely dependent on the vegetation type, savannas by-and-large exhibit a loss in carbon and nitrogen in surface soils, albeit to varying degrees. By contrast, soil C and N in temperate and boreal needle-leaf forests have been observed to be immune to fire. Fire also alters the composition and quantity of biomass.

- Biomass could refer either to the trees and shrubs (terrestrial aboveground biomass) or root networks under the soil (belowground/root biomass). Aboveground biomass also constitutes grasses and even dead leaves and shoots that fall off the vegetation (litter).

- The study employed a LiDAR sensor (light detection and ranging) on a drone to ascertain aboveground woody biomass (in terms of tree density), and a ground penetrating radar to determine belowground woody coarse lateral root biomass.

- The measurement of belowground biomass obtained via the aforementioned non-invasive method was supplemented with field-based measurements of woody taproot biomass.

- The Kruger National Park (KNP) offers an excellent template to study the effects of varying fire regimes, their interplay with rainfall, and their ultimate impact on vegetation. For one, the park contains a wide climatic gradient in terms of precipitation and soil types. Secondly, KNP has been subject to a large experiment in fire manipulation that has been running since 1954.

- The study found that fire suppression, compared to triennial fires, increased tree height, tree cover and aboveground woody biomass.

- Fire suppression or less frequent fires also contributed to an increase in belowground woody biomass, but not in the same proportion as aboveground biomass as usually believed. The reason behind this is that trees in savannas that burn quite frequently invest heavily in belowground root biomass in order to be able to recover after fire. ‘This result contradicts the assumption of constant root-to-shoot ratio applied elsewhere to estimate belowground carbon.’

- The soil organic carbon remained largely unaffected by changes in fire frequencies. Ecologists have repeatedly argued that fire suppression and tree planting can actually reduce biodiversity in savanna and grassland ecosystems.

- Tree planting programmes also tend to fail because seed germination rates are quite low in savanna and grassland biomes. Not only that, they may actually be counterproductive as an altogether absence of fire allows woody vegetation to develop for long periods of time, and leads to a massive fire when fire eventually occurs.

- Regular fires in the African grassland help the growth of new vegetation, are non-polluting and necessary for the survival of several animals.

- Some fires are started to stimulate new growth of nutritious grass for their animals, others are used to control the numbers of parasitic ticks or manage the growth of thorny scrub.

- Without fires, many Savannas – and the animals they support – wouldn’t exist. And lighting them is a key management activity in many of the iconic protected areas of Africa.

- Savanna fires keep tree cover low and prevent forests from encroaching on the grassland. When tree cover is high, as in a forest, fires cannot spread as easily, halting the savanna’s advance into the forest.

- Stamping out fires in the African savanna generates smaller carbon sequestration gains.

- Savannas consist of a continuous layer of grass interspersed with scattered trees or shrubs, and cover approx. 10 million square kilometers of tropical Africa.

- African savanna fires, almost all resulting from human activities, may produce as much as a third of the total global emissions from biomass burning.

- Emissions from African savanna burning are known to be transported over the mid-Atlantic, south Pacific and Indian oceans; but to study fully the transport of regional savanna burning and the seasonality of the atmospheric circulation must be considered simultaneously.

- Contrary to expectations, most fires are left to burn uncontrolled, so that there is no strong diurnal cycle in the fire frequency. The knowledge gained from this study regarding the distribution and variability of fires will aid monitoring of the climatically important trace gases emitted from burning biomass.

- The effect of north African savanna fires on atmospheric CO2 is investigated using a tracer transport model. The model uses winds from operational numerical weather prediction analyses and provides CO2 concentrations as a function of space and time.

- After a spin-up period of several years, biomass-burning sources are added, and model experiments are run for an additional year, utilizing various estimates of CO2 sources. The various model experiments show that biomass burning in the north African savannas significantly affects CO2 concentrations in South America.

- Smoke from fires contains a high percentage of black carbon particulates, one type of aerosol. These aerosols efficiently absorb sunlight much like the Earth’s surface does on a hot afternoon. As the suspended aerosols absorb sunlight, they heat the air and create a warm layer that prevents air from the Earth’s warmed surface from rising above it.

- Kruger National Park is a South African National Park and one of the largest game reserves in Africa. It covers an area of 19,623 km2 (7,576 sq mi) in the provinces of Limpopo and Mpumalanga in northeastern South Africa, and extends 360 km (220 mi) from north to south and 65 km (40 mi) from east to west. The administrative headquarters are in Skukuza.

- Areas of the park were first protected by the government of the South African Republic in 1898, and it became South Africa's first national park in 1926.

- To the west and south of the Kruger National Park are the two South African provinces of Limpopo and Mpumalanga, respectively. To the north is Zimbabwe, and to the east is Mozambique.

- It is now part of the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park, a peace park that links Kruger National Park with the Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe, and with the Limpopo National Park in Mozambique.

- The park is part of the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere, an area designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as an International Man and Biosphere Reserve.

About The ‘Water Tower of Asia’

About The ‘Water Tower of Asia’

- Mountains play a role in the birth and growth of human civilisations. This role is particularly observed with respect to the flow of rivers originating from the mountains, thus earning for these mountains the name, “Water Towers of the World”.

- In Central and South Asia, the imperative is clear for the governance of the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH)—a mountain range that stretches 3,500 km and straddles eight countries – Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, Bangladesh.

- The HKH is the source of 10 large rivers of Asia, serving the water needs of 16 countries; at least 2 billion people live in these basins. For the sheer size of the HKH, and that of the population it serves, these mountains are known as the “Water Tower of Asia”.

- The river basins are: Yellow, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween, Irrawaddy, Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus, Amu Darya, and Tarim. Their total area is 8.99 million sq. km, of which 2.79 million sq. km lies within the HKH region.

- Today the HKH is a hotspot for water crises and their impacts. As early as in 1992, the idea of Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) has been proffered as a strategy for managing water resources in a holistic manner and thereby avoiding resource challenges from escalating into crises.

- IWRM has remained marginal in its utility, however. This report builds on existing knowledge about integrated governance and offers a framework for bringing IWRM closer to practice in managing the HKH.

- The Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) mountains provide two billion people a vital regional lifeline via water for food (especially irrigation), water for energy (hydropower), and water for ecosystem services (riparian habitats, environmental flows, and rich and diverse cultural values).

- Glacier and snow melt are important components of streamflow in the region; their relative contribution increases with altitude and proximity to glacier and snow reserves.

- Groundwater, from springs in the mid-hills of the HKH, is also an important contributor to river baseflow, but the extent of groundwater contribution to river flow is not known due to limited scientific studies.