- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Stubble Management - Waste to Wealth

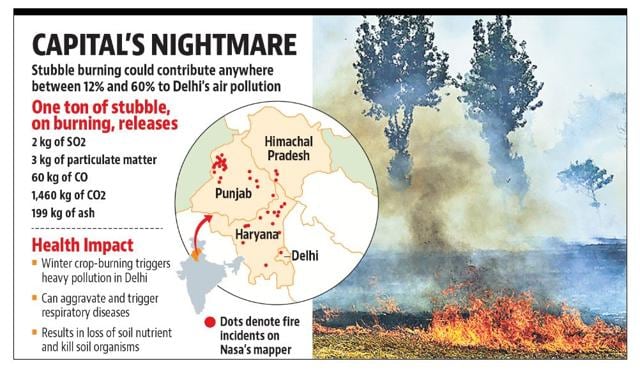

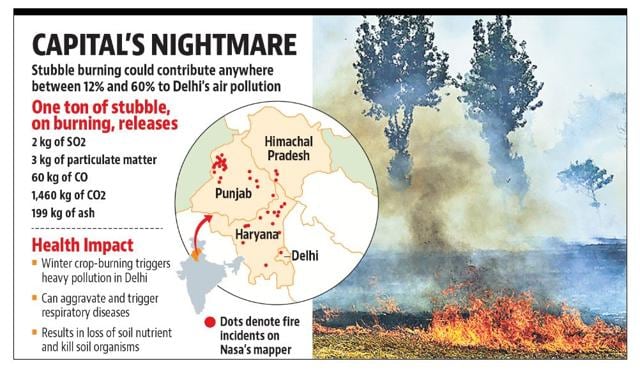

Every year, the onset of winter season in the northern India begins with the question mark on air quality due to stubble burning.

Issues associated to Stubble Burning

Issues associated to Stubble Burning

- The problem of stubble burning has been the most serious issue in media reports and social media sites which emphasized only on “instant solutions” and people tending to pontificate or sensationalise rather than reason.

Issues associated to Stubble Burning

Issues associated to Stubble Burning

- Difference between quantity of farm waste and window for disposal: The paddy stubble poses major challenges in North India such as the quantity of the farm waste is humongous and the window for disposing of it is too small.

- No incentive to collect the stubble: With the availability of wheat straw for cattle fodder, farmers have little or no incentive to collect the stubble.

- Deterioration of Soil’s organic content: The stubble-burning deteriorates the soil’s organic content, essential nutrients and microbial activity, which together will reduce the soil’s long-term productivity.

- Implementation of laws lacks strength: The burning of crop residue is a crime under Section 188 of the IPC and under the Air and Pollution Control Act of 1981 but the government’s implementation lacks strength.

- Stubble burning making contribution to environmental pollution: A study estimates that crop residue burning released 149.24 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2), over 9 million tonnes of carbon monoxide (CO), 0.25 million tonnes of oxides of sulphur (SOX), 1.28 million tonnes of particulate matter and 0.07 million tonnes of black carbon.

- The heat from burning paddy straw penetrates 1 centimeter into the soil, elevating the temperature to 33.8 to 42.2 degree Celsius.

- The Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) issued tariff orders for biomass gasifier/biogas power, which became inconsequential with solar and wind power tariffs declining to 33 per cent of that of biomass power.

- The Ministry of New & Renewable Energy (MNRE) supported “pilot projects” of manure to bio-CNG and the task forces made recommendations on turning farm waste to advanced biofuels.

- Liquid biofuels encompass bioethanol, drop-in fuels, bio-oil and bio-methanol: The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas’s “JI-VAN” Scheme provides viability gap funding to enable meeting the blending target of 20 per cent by 2030.

- The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas’s SATAT scheme, announced in 2018, envisaged 5,000 plants, typically rated 3,000 tons/year bio-CNG, consuming about 33,000 tons/year of paddy stubble.

- Non-productive efforts from the government: In the preceding decade, task forces were constituted to evaluate the techno-economic viability as well as develop business models for farm waste to energy projects, with “stubble burning” being the focused area but these efforts failed to fructify.

- Reluctance from farmers’ on adopting alternatives to stubble burning: In India, although both the Centre and state governments have encouraged alternatives, for example by promoting the use of new machines and technologies, farmers have been reluctant to adopt them.

- The farmers believe that stubble-burning to be easier, low cost and time-efficient, compared to alternatives that demand more time, investment and labour.

- Limitations of agreements and financing instruments: It was in 2018 that the “pilot projects” on turning farm waste to advanced biofuels were morphed into the Gobardhan Scheme and National Policy on Biofuels, albeit with limitations related to off-take agreements and financing instruments i.e. impeding capacity creation.

- Negligible implementation of subsidy from state governments: In 2019, the governments of Punjab and Haryana announced Rs 2,500/acre as a bonus to small farmers who avoid burning stubble but there has been the negligible implementation of this subsidy in 2019 or 2020.

- Biomass Power Plants: The Punjab Energy Development Agency has actively supported the biomass power sector, including provisioning for a high feed-in tariff of Rs8/ KWh, but capacity creation, as well as stubble consumption, is relatively low.

- A sharp decline in solar and wind tariffs is a constraint and the costs of establishing a year-round “bankable” supply chain for paddy straw bales is another deterrent.

- On-field management of stubble: The On-field management involves mulching the stubble into fields by customized machinery.

- The subsidy is given for purchasing equipment but this takes care of only 20 per cent of the cost besides costs, farmers are also saddled with operation and maintenance issues and the time factor isn’t resolved either.

- The mulching carbon-rich stubble impacts soil Carbon:Nitrogen ratio, necessitating proper nitrogenous fertiliser management apart from the potential surface accumulation of potassium (which is less mobile than nitrogen).

- The Punjab Agriculture University has solutions but adoption by millions of farmers, requires calibrated implementation and enormous extension services.

- Emphasis on cultivation of silage crops: The country has surplus grains and grain cultivation has scaled up in UP, MP, Chhattisgarh, and Bihar but the alternatives for farmers of Punjab could be the cultivation of silage crops (hybrid Sorghum, hybrid Napier grass and maize).

- The silage crops have a high yield, enabling farmers to meet the feedstock needs of cattle, can also be used to produce biofuels plants and the cultivated area can be interspersed with horticulture.

- Biomass Depots: It is essential to undertake on-field baling of stubble, aggregate bales in a depot and enter into bankable agreements for supplies to Bio-Energy Plants.

- It is imperative that India adopts a technology-agnostic policy for promoting advanced biofuels and attractive “offtake” rates for 1G Ethanol supports Sugarcane Farmers but they constitute only 4 per cent of the farmer households in India.

- The processing of agriculture residues to bio-CNG and compost will benefit many more farmer households, with manifold collateral benefits that accrue from assured availability of sustainable energy/ mobility.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies