- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Crime and Female Labour Force Participation

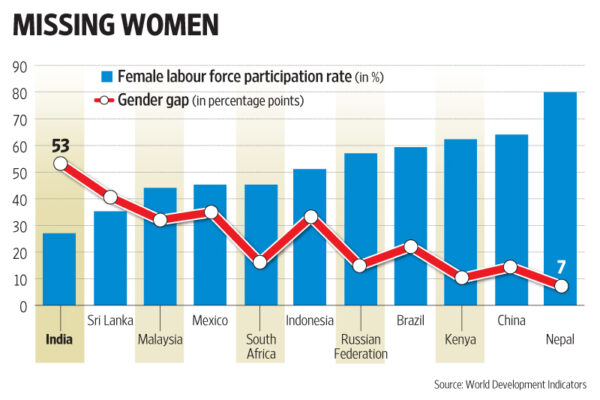

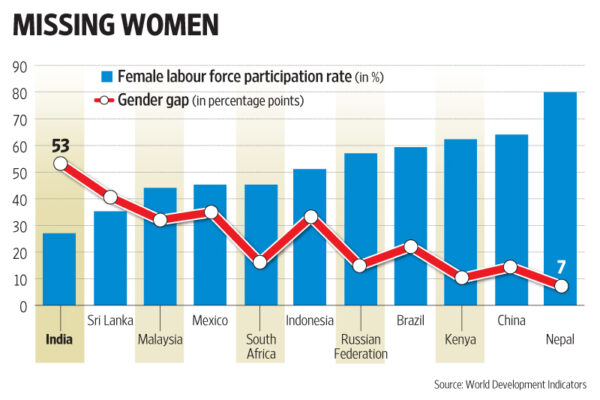

India’s female labour force participation rate (FLFPR) is a puzzling feature of Indian economy. Violence against women and girls, among other reasons, are barriers that restrict their mobility and reduces the likelihood of their labour force participation.

Female Labour Force Participation in India

- Although number of working-age women grew by 25% over the last two decades, the number of women in jobs declined by 10 million.

- The 2021 Global Gender Gap Index revealed that India ranks 140th of 156 countries, compared to its 98th position in 2006.

- India’s FLFPR (24.5% in 2018-19) has been declining and is well below the global average (45%).

- Between 2011 and 2019, there has been an increase in the rate of women enrolling in higher education.

- As more women pursue higher education, it is natural to assume them to enter into the job market.

- However, as India’s FLFPR decreased from 2000s, the unemployment rate of women has rapidly been increasing.

- This is contradiction as more women pursue higher education but still they are less women in the labour workforce.

- (Main reason) Crimes against women and girls (CaW&G)

- Domestic responsibilities and the burden of unpaid care,

- Occupational segregation and limited opportunities to enter non-traditional sectors,

- Inadequate supportive infrastructure such as creches or piped water and cooking fuel,

- Lack of safety and mobility options,

- The interplay of social norms and identities.

Crime against women

As per a study from the National Crime Records Bureau data, Kidnapping and abduction (K&A), and sexual harassment and molestation are the main causes that prevent women from participants in labour force. Other highlights of the study- While the all-India FLFPR saw an 8 %-point decline, the rate of CaW&G more than tripled to 57.9%.

- The rates of K&A and sexual harassment increased by more than three times, and the rates of rape and molestation about doubled.

- A state-level analysis shows that there is a low but negative correlation between the FLFPR and rate of CaW&G, as well as the FLFPR and K&A rate.

- Himachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Chhattisgarh and Sikkim maintain a high FLFPR and low rate of crime in comparison with other states and Union territories.

- It had the lowest FLFPR in India.

- Tripura saw the biggest decline in FLFPR, as it fell by over 24% points

Causes of low participation of women in labor market

- Occupational segregation

- Between 1977 and 2017, India’s economy witnessed a surge in the contribution of services (39 percent to 53 percent) and industry (33 percent to 27 percent) to GDP.

- However, women received less than 19 percent of new employment opportunities generated in India’s 10 fastest-growing occupations.

- Increased mechanization

- In agriculture, the use of new equipment displaced women.

- Nearly 12 million Indian women could lose their jobs by 2030 due to automation.

- The income effects

- With increasing household incomes, the need for additional income reduced.

- Consequently, families withdrew women from labour as a signal of prosperity

- 9 percent of the total decline in the female labour force participation rate between 2005 to 2010 was due to income effect.

- With increasing household incomes, the need for additional income reduced.

- Gender gaps in higher education and skill training

- As of 2018-19, only 2 percent of working-age women received formal vocational training, of which 47 percent did not join the labour force.

- Social norms

- Women regularly sacrifice wages, career progression, and education opportunities to meet family responsibilities, safety considerations, and other restrictions.

Suggestions

- The government, the private sector, media, need to work together to improve working conditions, reduce wage gaps and change mindsets.

- State governments may establish gender-based employment targets for urban public works.

- Central or state governments can consider introducing wage subsidies to incentivise hiring women in micro, small and medium enterprises.

- Governments could introduce mandatory or incentives-based gender targets across skill training institutions.

- Firms and NGOs should come together to invest in bridging the digital gender divide, offering free mobile phones and laptops to girls from disadvantaged communities, and offer long term training.

Summing Up

- There is need of a comprehensive mechanism that involves the state, institutions, communities and households to address this challenge.

- Adopting a ‘SAFETY’ framework—focused on Services, Attitudes, Focus on community, Empowerment of women, Transport, and Youth interventions—can be a critical element in framing policies to stop crimes against women and girls.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies