EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

‘AFSPA empowers military, cannot solve insurgency’: Northeast activists say

The Nagaland Cabinet on 7 December 2021 recommended that the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958 be repealed from the state after the incident in Mon district in which security forces gunned down 13 civilians. This has been a long-standing demand in the North eastern states. After the firing, Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio and Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma have both called for repeal of AFSPA.

Nagaland leaders feel the killings have the potential to create mistrust in the Indian government and derail the peace process currently underway between the Centre and the Naga insurgents groups.

What is AFSPA?

The Act in its original form was promulgated by the British in response to the Quit India movement in 1942. After Independence, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to retain the Act, which was first brought in as ordnance and then notified as an Act in 1958.

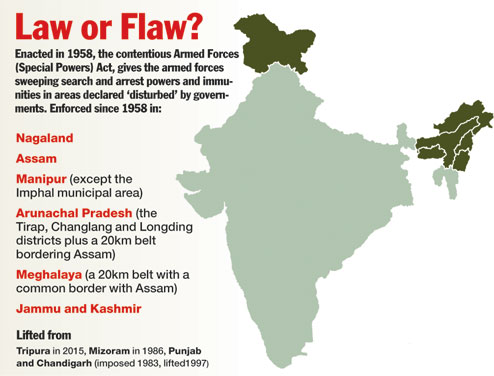

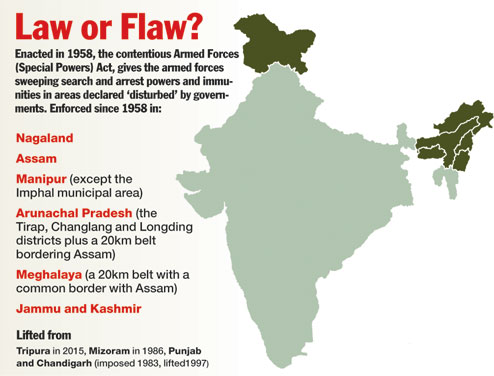

AFSPA has been imposed on the Northeast states, Jammu & Kashmir, and Punjab during the militancy years. Punjab was the first state from where it was repealed, followed by Tripura and Meghalaya. It remains in force in Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, J&K, and parts of Arunachal Pradesh.

AFSPA provides for special powers for the armed forces that can be imposed by the Centre or the Governor of a state, on the state or parts of it, after it is declared “disturbed’’ under Section 3. The Act defines these as areas that are “disturbed or dangerous condition that the use of armed forces in aid of the civil power is necessary’’. AFSPA has been used in areas where militancy has been prevalent.

The Act, which has been called draconian, gives sweeping powers to the armed forces. It allows them to open fire’, even causing death, against any person in contravention to the law or carrying arms and ammunition. It gives them powers to arrest individuals without warrants, on the basis of “reasonable suspicion”, and also search premises without warrants.

The Act further provides blanket impunity to security personnel involved in such operations: There can be no prosecution or legal proceedings against them without the prior approval of the Centre.

Are there safety nets?

While the Act gives powers to security forces to open fire, this cannot be done without prior warning given to the suspect. In the Mon firing, it has been an issue of discussion whether the security forces gave prior warning before opening fire at the vehicle carrying coal miners, and then later at a violent mob.

The Act further says that after any suspects apprehended by security forces should be handed over to the local police station within 24 hours. It says armed forces must act in cooperation with the district administration and not as an independent body. In the Mon operation, local law-enforcement agencies have said they were unaware of the operation.

What attempts have been made to repeal AFSPA in the past?

In 2000, Manipur activist Irom Sharmila began a hunger-strike, which would continue for 16 years, against AFSPA. In 2004, the UPA government set up a five-member committee under a former Supreme Court Judge. The Justice Jeevan Reddy Commission submitted its report in 2005, saying AFSPA had become a symbol of oppression and recommending its repeal. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission, headed by Veeerapa Moily, endorsed these recommendations.

Former Home Secretary G K Pillai too supported the repeal of AFSPA, and former Home Minister P Chidambaram once said the Act, if not repealed, should at least be amended. But opposition from the Defence Ministry stalled any possible decision.

The UPA set up a cabinet sub-committee to continue looking into the matter. The NDA government subsequently dropped the sub-committee and also rejected the findings of the Reddy Commission.

How often have state governments opposed it?

While the Act empowers the Centre to unilaterally take a decision to impose AFSPA, this is usually done informally in consonance with the state government. The Centre can take a decision to repeal AFSPA after getting a recommendation from the state government. However, Nagaland, which has freshly recommended a repeal, had raised the demand earlier too, without success.

The Centre had also imposed AFSPA in Tripura in 1972 despite opposition from the then state government.

In Manipur, former Congress Chief Minister Okram Ibobi Singh had told The Indian Express in 2012 that he was opposed to the repeal of AFSPA in light of the dangerous law and order situation.

Many politicians have built their careers on an anti-AFSPA stance, including incumbent Manipur Chief Minister N Biren Singh, who contested his first election in 2002 in order to “fight AFSPA” after 10 civilians had been gunned down by the 8th Assam Rifles at Malom Makha Leikai in 2000.

What has been the social fallout?

Nagaland and Mizoram faced the brunt of AFSPA in the 1950s, including air raids and bombings by the Indian military. Allegations have been made against security forces of mass killings and rape.

It is in Manipur that the fallout has been perhaps best documented. The Malom massacre in 2000, and the killing and alleged rape of Thangjam Manorama led to the subsequent repeal of AFSPA from the Imphal municipal area.

Human rights activists have said the Act has often been used to settle private scores, such as property disputes, with false tip-offs provided by local informants to security forces.

Have these excesses been probed?

In 2012, the Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association of Manipur filed a case in the Supreme Court alleging 1,528 fake encounters between 1979 and 2012. Activists said these peaked in 2008-09.

The Supreme Court set up a three-member committee under former judge Santosh Hegde and including former Chief Election Commissioner J M Lyngdoh and former Karnataka DGP Ajay Kumar Singh. The committee investigated six cases of alleged fake encounters, including the 2009 killing of 12-year-old Azad Khan, and submitted a report with the finding that all six were fake encounters.

The Court set up a special investigation team that included five CBI officials and one National Human Rights Commission member. The CBI booked Army Major Vijay Singh Balhara in Khan’s death in 2018, but there has been no prosecution against security forces in other cases.

Activists note that AFSPA creates an atmosphere of impunity among even state agencies such as the Manipur Police and their Manipur Commandos, believed to be responsible for most encounters in the state, some of them jointly with Assam Rifles.

The SIT has investigated 39 cases involving deaths of 85 civilians so far, and filed the final reports in 32 cases. While 100 Manipur police personnel have been indicted, no action has been taken against Assam Rifles personnel with the exception of the Khan killing.

The Nagaland Cabinet on 7 December 2021 recommended that the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958 be repealed from the state after the incident in Mon district in which security forces gunned down 13 civilians. This has been a long-standing demand in the North eastern states. After the firing, Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio and Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma have both called for repeal of AFSPA.

Nagaland leaders feel the killings have the potential to create mistrust in the Indian government and derail the peace process currently underway between the Centre and the Naga insurgents groups.

What is AFSPA?

The Act in its original form was promulgated by the British in response to the Quit India movement in 1942. After Independence, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to retain the Act, which was first brought in as ordnance and then notified as an Act in 1958.

AFSPA has been imposed on the Northeast states, Jammu & Kashmir, and Punjab during the militancy years. Punjab was the first state from where it was repealed, followed by Tripura and Meghalaya. It remains in force in Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, J&K, and parts of Arunachal Pradesh.

AFSPA provides for special powers for the armed forces that can be imposed by the Centre or the Governor of a state, on the state or parts of it, after it is declared “disturbed’’ under Section 3. The Act defines these as areas that are “disturbed or dangerous condition that the use of armed forces in aid of the civil power is necessary’’. AFSPA has been used in areas where militancy has been prevalent.

The Act, which has been called draconian, gives sweeping powers to the armed forces. It allows them to open fire’, even causing death, against any person in contravention to the law or carrying arms and ammunition. It gives them powers to arrest individuals without warrants, on the basis of “reasonable suspicion”, and also search premises without warrants.

The Act further provides blanket impunity to security personnel involved in such operations: There can be no prosecution or legal proceedings against them without the prior approval of the Centre.

Are there safety nets?

While the Act gives powers to security forces to open fire, this cannot be done without prior warning given to the suspect. In the Mon firing, it has been an issue of discussion whether the security forces gave prior warning before opening fire at the vehicle carrying coal miners, and then later at a violent mob.

The Act further says that after any suspects apprehended by security forces should be handed over to the local police station within 24 hours. It says armed forces must act in cooperation with the district administration and not as an independent body. In the Mon operation, local law-enforcement agencies have said they were unaware of the operation.

What attempts have been made to repeal AFSPA in the past?

In 2000, Manipur activist Irom Sharmila began a hunger-strike, which would continue for 16 years, against AFSPA. In 2004, the UPA government set up a five-member committee under a former Supreme Court Judge. The Justice Jeevan Reddy Commission submitted its report in 2005, saying AFSPA had become a symbol of oppression and recommending its repeal. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission, headed by Veeerapa Moily, endorsed these recommendations.

Former Home Secretary G K Pillai too supported the repeal of AFSPA, and former Home Minister P Chidambaram once said the Act, if not repealed, should at least be amended. But opposition from the Defence Ministry stalled any possible decision.

The UPA set up a cabinet sub-committee to continue looking into the matter. The NDA government subsequently dropped the sub-committee and also rejected the findings of the Reddy Commission.

How often have state governments opposed it?

While the Act empowers the Centre to unilaterally take a decision to impose AFSPA, this is usually done informally in consonance with the state government. The Centre can take a decision to repeal AFSPA after getting a recommendation from the state government. However, Nagaland, which has freshly recommended a repeal, had raised the demand earlier too, without success.

The Centre had also imposed AFSPA in Tripura in 1972 despite opposition from the then state government.

In Manipur, former Congress Chief Minister Okram Ibobi Singh had told The Indian Express in 2012 that he was opposed to the repeal of AFSPA in light of the dangerous law and order situation.

Many politicians have built their careers on an anti-AFSPA stance, including incumbent Manipur Chief Minister N Biren Singh, who contested his first election in 2002 in order to “fight AFSPA” after 10 civilians had been gunned down by the 8th Assam Rifles at Malom Makha Leikai in 2000.

What has been the social fallout?

Nagaland and Mizoram faced the brunt of AFSPA in the 1950s, including air raids and bombings by the Indian military. Allegations have been made against security forces of mass killings and rape.

It is in Manipur that the fallout has been perhaps best documented. The Malom massacre in 2000, and the killing and alleged rape of Thangjam Manorama led to the subsequent repeal of AFSPA from the Imphal municipal area.

Human rights activists have said the Act has often been used to settle private scores, such as property disputes, with false tip-offs provided by local informants to security forces.

Have these excesses been probed?

In 2012, the Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association of Manipur filed a case in the Supreme Court alleging 1,528 fake encounters between 1979 and 2012. Activists said these peaked in 2008-09.

The Supreme Court set up a three-member committee under former judge Santosh Hegde and including former Chief Election Commissioner J M Lyngdoh and former Karnataka DGP Ajay Kumar Singh. The committee investigated six cases of alleged fake encounters, including the 2009 killing of 12-year-old Azad Khan, and submitted a report with the finding that all six were fake encounters.

The Court set up a special investigation team that included five CBI officials and one National Human Rights Commission member. The CBI booked Army Major Vijay Singh Balhara in Khan’s death in 2018, but there has been no prosecution against security forces in other cases.

Activists note that AFSPA creates an atmosphere of impunity among even state agencies such as the Manipur Police and their Manipur Commandos, believed to be responsible for most encounters in the state, some of them jointly with Assam Rifles.

The SIT has investigated 39 cases involving deaths of 85 civilians so far, and filed the final reports in 32 cases. While 100 Manipur police personnel have been indicted, no action has been taken against Assam Rifles personnel with the exception of the Khan killing.

Next

previous

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

The Nagaland Cabinet on 7 December 2021 recommended that the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958 be repealed from the state after the incident in Mon district in which security forces gunned down 13 civilians. This has been a long-standing demand in the North eastern states. After the firing, Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio and Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma have both called for repeal of AFSPA.

Nagaland leaders feel the killings have the potential to create mistrust in the Indian government and derail the peace process currently underway between the Centre and the Naga insurgents groups.

What is AFSPA?

The Act in its original form was promulgated by the British in response to the Quit India movement in 1942. After Independence, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to retain the Act, which was first brought in as ordnance and then notified as an Act in 1958.

AFSPA has been imposed on the Northeast states, Jammu & Kashmir, and Punjab during the militancy years. Punjab was the first state from where it was repealed, followed by Tripura and Meghalaya. It remains in force in Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, J&K, and parts of Arunachal Pradesh.

AFSPA provides for special powers for the armed forces that can be imposed by the Centre or the Governor of a state, on the state or parts of it, after it is declared “disturbed’’ under Section 3. The Act defines these as areas that are “disturbed or dangerous condition that the use of armed forces in aid of the civil power is necessary’’. AFSPA has been used in areas where militancy has been prevalent.

The Act, which has been called draconian, gives sweeping powers to the armed forces. It allows them to open fire’, even causing death, against any person in contravention to the law or carrying arms and ammunition. It gives them powers to arrest individuals without warrants, on the basis of “reasonable suspicion”, and also search premises without warrants.

The Act further provides blanket impunity to security personnel involved in such operations: There can be no prosecution or legal proceedings against them without the prior approval of the Centre.

Are there safety nets?

While the Act gives powers to security forces to open fire, this cannot be done without prior warning given to the suspect. In the Mon firing, it has been an issue of discussion whether the security forces gave prior warning before opening fire at the vehicle carrying coal miners, and then later at a violent mob.

The Act further says that after any suspects apprehended by security forces should be handed over to the local police station within 24 hours. It says armed forces must act in cooperation with the district administration and not as an independent body. In the Mon operation, local law-enforcement agencies have said they were unaware of the operation.

What attempts have been made to repeal AFSPA in the past?

In 2000, Manipur activist Irom Sharmila began a hunger-strike, which would continue for 16 years, against AFSPA. In 2004, the UPA government set up a five-member committee under a former Supreme Court Judge. The Justice Jeevan Reddy Commission submitted its report in 2005, saying AFSPA had become a symbol of oppression and recommending its repeal. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission, headed by Veeerapa Moily, endorsed these recommendations.

Former Home Secretary G K Pillai too supported the repeal of AFSPA, and former Home Minister P Chidambaram once said the Act, if not repealed, should at least be amended. But opposition from the Defence Ministry stalled any possible decision.

The UPA set up a cabinet sub-committee to continue looking into the matter. The NDA government subsequently dropped the sub-committee and also rejected the findings of the Reddy Commission.

How often have state governments opposed it?

While the Act empowers the Centre to unilaterally take a decision to impose AFSPA, this is usually done informally in consonance with the state government. The Centre can take a decision to repeal AFSPA after getting a recommendation from the state government. However, Nagaland, which has freshly recommended a repeal, had raised the demand earlier too, without success.

The Centre had also imposed AFSPA in Tripura in 1972 despite opposition from the then state government.

In Manipur, former Congress Chief Minister Okram Ibobi Singh had told The Indian Express in 2012 that he was opposed to the repeal of AFSPA in light of the dangerous law and order situation.

Many politicians have built their careers on an anti-AFSPA stance, including incumbent Manipur Chief Minister N Biren Singh, who contested his first election in 2002 in order to “fight AFSPA” after 10 civilians had been gunned down by the 8th Assam Rifles at Malom Makha Leikai in 2000.

What has been the social fallout?

Nagaland and Mizoram faced the brunt of AFSPA in the 1950s, including air raids and bombings by the Indian military. Allegations have been made against security forces of mass killings and rape.

It is in Manipur that the fallout has been perhaps best documented. The Malom massacre in 2000, and the killing and alleged rape of Thangjam Manorama led to the subsequent repeal of AFSPA from the Imphal municipal area.

Human rights activists have said the Act has often been used to settle private scores, such as property disputes, with false tip-offs provided by local informants to security forces.

Have these excesses been probed?

In 2012, the Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association of Manipur filed a case in the Supreme Court alleging 1,528 fake encounters between 1979 and 2012. Activists said these peaked in 2008-09.

The Supreme Court set up a three-member committee under former judge Santosh Hegde and including former Chief Election Commissioner J M Lyngdoh and former Karnataka DGP Ajay Kumar Singh. The committee investigated six cases of alleged fake encounters, including the 2009 killing of 12-year-old Azad Khan, and submitted a report with the finding that all six were fake encounters.

The Court set up a special investigation team that included five CBI officials and one National Human Rights Commission member. The CBI booked Army Major Vijay Singh Balhara in Khan’s death in 2018, but there has been no prosecution against security forces in other cases.

Activists note that AFSPA creates an atmosphere of impunity among even state agencies such as the Manipur Police and their Manipur Commandos, believed to be responsible for most encounters in the state, some of them jointly with Assam Rifles.

The SIT has investigated 39 cases involving deaths of 85 civilians so far, and filed the final reports in 32 cases. While 100 Manipur police personnel have been indicted, no action has been taken against Assam Rifles personnel with the exception of the Khan killing.

The Nagaland Cabinet on 7 December 2021 recommended that the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), 1958 be repealed from the state after the incident in Mon district in which security forces gunned down 13 civilians. This has been a long-standing demand in the North eastern states. After the firing, Nagaland Chief Minister Neiphiu Rio and Meghalaya Chief Minister Conrad Sangma have both called for repeal of AFSPA.

Nagaland leaders feel the killings have the potential to create mistrust in the Indian government and derail the peace process currently underway between the Centre and the Naga insurgents groups.

What is AFSPA?

The Act in its original form was promulgated by the British in response to the Quit India movement in 1942. After Independence, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru decided to retain the Act, which was first brought in as ordnance and then notified as an Act in 1958.

AFSPA has been imposed on the Northeast states, Jammu & Kashmir, and Punjab during the militancy years. Punjab was the first state from where it was repealed, followed by Tripura and Meghalaya. It remains in force in Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, Assam, J&K, and parts of Arunachal Pradesh.

AFSPA provides for special powers for the armed forces that can be imposed by the Centre or the Governor of a state, on the state or parts of it, after it is declared “disturbed’’ under Section 3. The Act defines these as areas that are “disturbed or dangerous condition that the use of armed forces in aid of the civil power is necessary’’. AFSPA has been used in areas where militancy has been prevalent.

The Act, which has been called draconian, gives sweeping powers to the armed forces. It allows them to open fire’, even causing death, against any person in contravention to the law or carrying arms and ammunition. It gives them powers to arrest individuals without warrants, on the basis of “reasonable suspicion”, and also search premises without warrants.

The Act further provides blanket impunity to security personnel involved in such operations: There can be no prosecution or legal proceedings against them without the prior approval of the Centre.

Are there safety nets?

While the Act gives powers to security forces to open fire, this cannot be done without prior warning given to the suspect. In the Mon firing, it has been an issue of discussion whether the security forces gave prior warning before opening fire at the vehicle carrying coal miners, and then later at a violent mob.

The Act further says that after any suspects apprehended by security forces should be handed over to the local police station within 24 hours. It says armed forces must act in cooperation with the district administration and not as an independent body. In the Mon operation, local law-enforcement agencies have said they were unaware of the operation.

What attempts have been made to repeal AFSPA in the past?

In 2000, Manipur activist Irom Sharmila began a hunger-strike, which would continue for 16 years, against AFSPA. In 2004, the UPA government set up a five-member committee under a former Supreme Court Judge. The Justice Jeevan Reddy Commission submitted its report in 2005, saying AFSPA had become a symbol of oppression and recommending its repeal. The Second Administrative Reforms Commission, headed by Veeerapa Moily, endorsed these recommendations.

Former Home Secretary G K Pillai too supported the repeal of AFSPA, and former Home Minister P Chidambaram once said the Act, if not repealed, should at least be amended. But opposition from the Defence Ministry stalled any possible decision.

The UPA set up a cabinet sub-committee to continue looking into the matter. The NDA government subsequently dropped the sub-committee and also rejected the findings of the Reddy Commission.

How often have state governments opposed it?

While the Act empowers the Centre to unilaterally take a decision to impose AFSPA, this is usually done informally in consonance with the state government. The Centre can take a decision to repeal AFSPA after getting a recommendation from the state government. However, Nagaland, which has freshly recommended a repeal, had raised the demand earlier too, without success.

The Centre had also imposed AFSPA in Tripura in 1972 despite opposition from the then state government.

In Manipur, former Congress Chief Minister Okram Ibobi Singh had told The Indian Express in 2012 that he was opposed to the repeal of AFSPA in light of the dangerous law and order situation.

Many politicians have built their careers on an anti-AFSPA stance, including incumbent Manipur Chief Minister N Biren Singh, who contested his first election in 2002 in order to “fight AFSPA” after 10 civilians had been gunned down by the 8th Assam Rifles at Malom Makha Leikai in 2000.

What has been the social fallout?

Nagaland and Mizoram faced the brunt of AFSPA in the 1950s, including air raids and bombings by the Indian military. Allegations have been made against security forces of mass killings and rape.

It is in Manipur that the fallout has been perhaps best documented. The Malom massacre in 2000, and the killing and alleged rape of Thangjam Manorama led to the subsequent repeal of AFSPA from the Imphal municipal area.

Human rights activists have said the Act has often been used to settle private scores, such as property disputes, with false tip-offs provided by local informants to security forces.

Have these excesses been probed?

In 2012, the Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association of Manipur filed a case in the Supreme Court alleging 1,528 fake encounters between 1979 and 2012. Activists said these peaked in 2008-09.

The Supreme Court set up a three-member committee under former judge Santosh Hegde and including former Chief Election Commissioner J M Lyngdoh and former Karnataka DGP Ajay Kumar Singh. The committee investigated six cases of alleged fake encounters, including the 2009 killing of 12-year-old Azad Khan, and submitted a report with the finding that all six were fake encounters.

The Court set up a special investigation team that included five CBI officials and one National Human Rights Commission member. The CBI booked Army Major Vijay Singh Balhara in Khan’s death in 2018, but there has been no prosecution against security forces in other cases.

Activists note that AFSPA creates an atmosphere of impunity among even state agencies such as the Manipur Police and their Manipur Commandos, believed to be responsible for most encounters in the state, some of them jointly with Assam Rifles.

The SIT has investigated 39 cases involving deaths of 85 civilians so far, and filed the final reports in 32 cases. While 100 Manipur police personnel have been indicted, no action has been taken against Assam Rifles personnel with the exception of the Khan killing.

Latest News

Latest News General Studies

General Studies