- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

Who are the Bru Refugees and What is the Agreement to Settle Them in Tripura?.

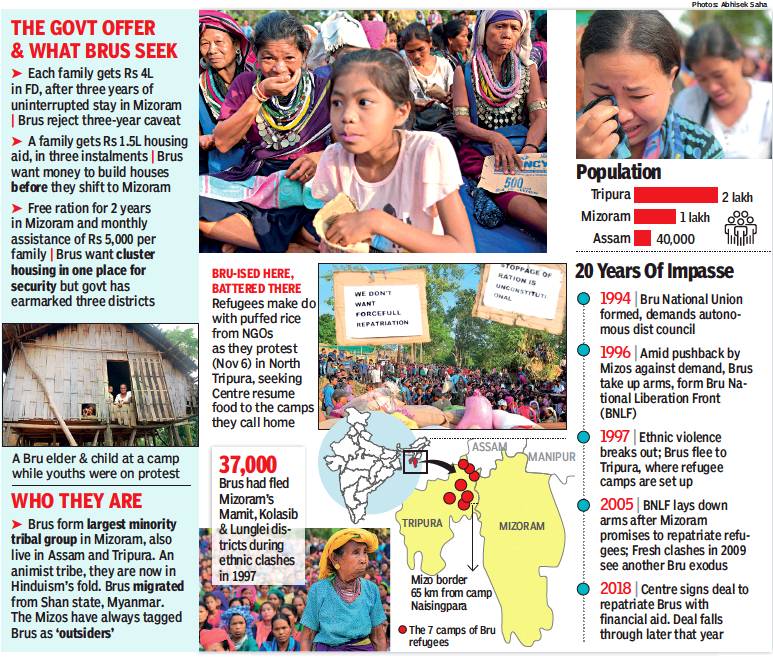

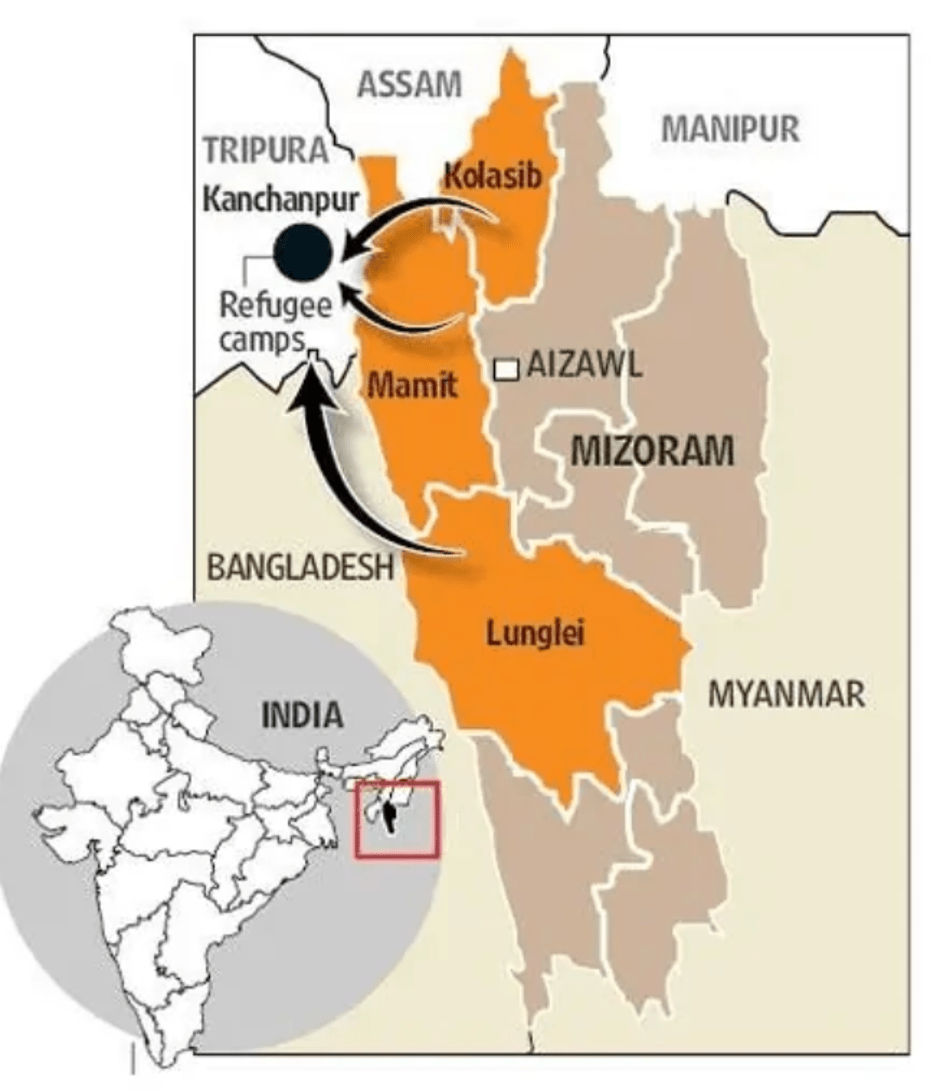

Twenty-three years after ethnic clashes in Mizoram forced 37,000 people of the Bru (or Reang) community to flee their homes to neighbouring Tripura, an agreement has been signed to allow them to remain permanently in the latter state.

The agreement among the Bru leaders and the governments of India, Tripura, and Mizoram, signed in New Delhi on January 16, gives the Bru the choice of living in either state. In several ways, the agreement has redefined the way in which internal displacement is treated in India.

What is in the Bru agreement?

All Bru currently living in temporary relief camps in Tripura will be settled in the state, if they want to stay on. The Bru who returned to Mizoram in the eight phases of repatriation since 2009, cannot, however, come back to Tripura.

To ascertain the numbers of those who will be settled, a fresh survey and physical verification of Bru families living in relief camps will be carried out. The Centre will implement a special development project for the resettled Bru; this will be in addition to the Rs 600 crore fund announced for the process, including benefits for the migrants.

Each resettled family will get 0.03 acre (1.5 ganda) of land for building a home, Rs 1.5 lakh as housing assistance, and Rs 4 lakh as a one-time cash benefit for sustenance. They will also receive a monthly allowance of Rs 5,000, and free rations for two years from the date of resettlement.

All cash assistance will be through Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT), and the state government will expedite the opening of bank accounts and the issuance of Aadhaar, permanent residence certificates, ST certificates, and voter identity cards to the beneficiaries.

When will the Bru resettlement take place?

Physical verification to identify beneficiaries will be carried out within 15 days of the signing of the deal. The land for resettlement will be identified within 60 days, and the land for allotment will be identified within 150 days.

The beneficiaries will get housing assistance, but the state government will build their homes and hand over possession. They will be moved to resettlement locations in four clusters, paving the way for the closure of the temporary camps within 180 days of the signing of the agreement. All dwelling houses will be constructed and payments completed within 270 days. Tripura Chief Minister Biplab Kumar Deb has said he hopes to wrap up the process even sooner — in six months.

Where will the Bru be resettled?

Revenue experts reckon 162 acres will be required. Chief Minister Deb has said that the effort will be to choose khash or government land, but since Tripura is a small state (only 10,491 sq km), his government would explore the possibility of diverting forest lands, even reserve forest areas if necessary, to grant the new entitlements.

Diverting forest land for human settlements will, however, need clearance from the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), which is likely to take at least three months. Deb has said that the central government has promised to provide funds, if needed, to acquire forest land or government land.

In what condition are the migrants now?

The Bru or Reang are a community indigenous to Northeast India, living mostly in Tripura, Mizoram, and Assam. In Tripura, they are recognised as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG). Over two decades ago, they were targeted by the Young Mizo Association (YMA), Mizo Zirwlai Pawl (MZP), and a few ethnic social organisations of Mizoram who demanded that the Bru be excluded from electoral rolls in the state. In October 1997, following ethnic clashes, nearly 37,000 Bru fled Mizoram’s Mamit, Kolasib, and Lunglei districts to Tripura, where they were sheltered in relief camps. Since then, over 5,000 have returned to Mizoram in nine phases of repatriation, while 32,000 people from 5,400 families still live in six relief camps in North Tripura.

Under a relief package announced by the Centre, a daily ration of 600 g rice was provided to every adult Bru migrant and 300 g to every minor. Some salt too, was given to each family. Every adult received a daily cash dole of Rs 5; every minor Rs 2.50. Meagre allocations were made from time to time for essentials such as soap, slippers, and mosquito nets.

Most migrants sold a part of their rice and used the money to buy supplies, including medicines. They depended on the wild for vegetables, and some of them have been practising slash-and-burn (jhum) cultivation in the forests.

They live in makeshift bamboo thatched huts, without permanent power supply and safe drinking water, with no access to proper healthcare services or schools.

How did the agreement come about?

In June 2018, Bru leaders signed an agreement in Delhi with the Centre and the two state governments, providing for repatriation to Mizoram. Most residents of the camps, however, rejected the “insufficient” terms of the agreement. Only 328 families returned to Mizoram, rendering the process redundant. The camp residents said the package did not guarantee their safety in Mizoram, and that they feared a repeat of the violence that had forced them to flee.

On November 16, 2019, Pradyot Kishore Debbarma, scion of Tripura’s erstwhile royal family, wrote to Home Minister Amit Shah seeking the resettlement of the Bru in the state. The Bru were originally from Tripura, and had migrated to Mizoram after their homes were flooded due to the commissioning of the Dumboor hydroelectric power project in South Tripura in 1976, he claimed. The very next day, Chief Minister Deb too, asked the Centre for permanent settlement of the Bru in Tripura.

How is this agreement different from the earlier initiatives taken for the Bru?

Successive state and central governments had thus far stressed only on peacefully repatriating the Bru, even though the enduring fear of ethnic violence remained a fundamental roadblock. The two other “durable solutions” for refugees and displaced persons suggested by the UN Refugee Agency — local integration or assimilation, and resettlement — were never explored.

Apart from their own Kaubru tongue, the Bru speak both Kokborok and Bangla, the two most widely spoken languages of the tribal and non-tribal communities of Tripura, and have an easy connection with the state. Their long stay in Tripura, albeit in exile and in terrible conditions, has also acquainted them very well with the state’s socio-political ecology.

Home Minister Shah, who presided over the signing of the agreement, hailed the “historic” resolution of the Bru issue. He thanked the Chief Ministers of Tripura and Mizoram, Pradyot Kishore Debbarma, and some social organisations for creating the conditions for the agreement.

Latest News

Latest News General Studies

General Studies