- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

Mar 19, 2022

MONSOONS CAN GO FOR A TOSS. WHAT WILL MEAN TO US?

Monsoon in India and west Africa may be in for changes due to greenhouse gases, new research has warned.

Key Findings

Key Findings

The role of coal in the energy transition

The role of coal in the energy transition

Key Findings

Key Findings

Genesis

Genesis

Genesis

Genesis

History

History

Key Findings

Key Findings

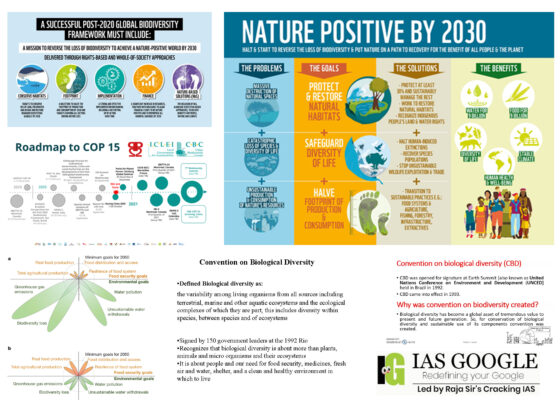

Geneva Biodiversity Conference

Geneva Biodiversity Conference

Key Findings

Key Findings

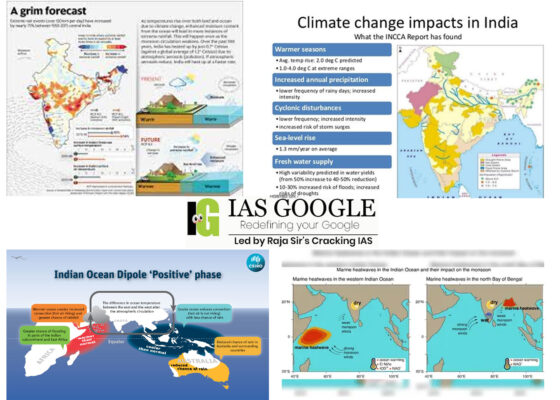

- Monsoon in India and west Africa — the most significant monsoon rainfall systems — may be in for changes due to greenhouse gases. The changes may be rapid or gradual in the present as well as near future.

- These are critical thresholds in massive Earth ecosystems such as the Amazon rainforest or the Greenland Ice Sheet that, when crossed, can lead to abrupt and irreversible changes in the systems.

- One of the prominent results of increased rainfall was the increase in vegetation in the Sahara Desert, evidence of which can be observed in the region’s paleoclimate records.

- Paleoclimate records in the form of sediments in the ocean or lake, limestone formations in caves, fossilised tree rings and ice cores give an estimate of how the climate behaved hundreds, thousands or even millions of years ago.

- The northward shift of the West African Monsoon had also caused significant changes in the social and cultural life of human settlements at the time, especially along the Nile River.

- Similarly, the ISM has undergone changes at various times in the past few thousand years. The destiny of the Indus Valley Civilisation was closely intertwined with that of the changing monsoon patterns.

- Indian monsoon plays vital role in India’s attempt to achieve food security.

- About 64 % Indian population depend on agriculture for their livelihood, which is based on southwest monsoon.

- Nearly 60 percent of the country’s farms lack irrigation facilities, leaving millions of farmers dependent on the rain.

- Monsoon is critical to replenish 81 reservoirs necessary for power generation, irrigation and drinking.

- Monsoon regime emphasizes the unity of India with the rest of Southeast Asian region.

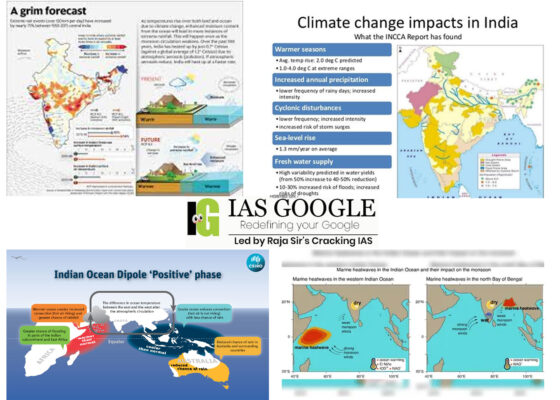

- One of the main factors that affect the onset of monsoon and its strength is the temperature gradient between the Indian subcontinent and the tropical Indian ocean

- Other factors influencing the monsoon – which brings more than 80% of the annual rainfall to South Asia – include the impact of El Niño and its counterpart La Niña. Then there’s the warming and cooling of the Indian and Atlantic oceans – the Indian Ocean Dipole and the Atlantic Niño. All these play a role in the monsoon, but it is not always clear which affects what, and how.

- Despite these changes and the decreasing trend, rainfall at the end of most seasons remains within 10% of the long period average. But with the variations across space increasing, that means little to farmers dependent on rain-fed agriculture. Some regions such as northern Karnataka and central Maharashtra have recently had rainfall deficits close to 50%.

- Long-term rainfall decline is worrying, especially if it is caused by oceans warming up as a result of climate change. This can alter the land-ocean temperature contrast and reduce the moisture demand over land during the monsoon.

- The ephemeral behaviour of the monsoon as its vicissitudes. These have clearly increased now, and made the work of scientists more difficult. But there is a silver lining. We now know that non-local influences are more important; it is easier to track them and improve our forecasting to the point where authorities have sufficient time to act before a flood or a storm.

- And since total rainfall has remained within 10% of the long period average, large water reservoirs are unnecessary. The real large-scale plan should be about capturing the rains, either by rainwater harvesting or agroforestry.

- With human-caused aerosol emissions expected to decrease in future, and with continued global warming, mean monsoon rainfall will increase by the end of the 21st century, as will variability in rainfall dispersal and frequency of localised extremely heavy rain events.

- The marine heat waves (MHWs) in the Indian Ocean region are impacting the ISM. Such heat waves are caused by an increase in the heat content of oceans, especially in the upper layers.

- The MHWs in the north Bay of Bengal and the western Indian Ocean reduce monsoon rainfall over central India, the study established. The occurrence in the north Bay of Bengal increases rainfall over the southern peninsular area.

- MHWs are huge patches of warm water and they change the way the atmospheric circulation works. The availability of more heat and moisture during an MHW makes the air move upwards which is known as ‘convection’.

- To compensate for the rise of convection with warm moist air, there is a subsidence of rainfall in other regions. The rising convection creates a low pressure below which pulls in the moisture-laden winds from other areas.

- When there are MHWs in the western Indian Ocean region, they pull the moisture-laden monsoon winds towards that region, not letting them move towards the Indian subcontinent.

- This weakens the monsoon system leading to dry conditions, mainly over central India. In the case of MHWs in the north Bay of Bengal, because of the location, more rainfall occurs over southern peninsular India while central and northern India remain dry.

- During an MHW, the average temperature of the ocean surface (up to a depth of 300 feet) goes 5-7 degrees Celsius above normal. Around 90 per cent of the warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions is absorbed by the oceans.

- The increase in marine heat waves was due to rapid warming in the Indian Ocean and strong El Nino events.

- The West African Monsoon, on the other hand, is getting affected by a host of inter-linked factors such as dust emissions from the Sahara Desert, evaporation from the lakes of the region and moisture feedbacks from vegetation.

- Another important factor in the case of WAM is a climate tipping point called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

- The Gulf Stream Ocean current usually carries warmer water from the tropics to higher latitudes and brings back colder water. But now, evidence suggests that the Gulf Stream is slowing down, which will lead to changes.

- The collapse of the AMOC might change the wind and rainfall patterns of the WAM which could lead to disruptions in the lives of 300 million, mostly agricultural people of west and central Africa who depend on the rainfall.

- The West African Monsoon is powered by the temperature difference between the cooler tropical Atlantic Ocean and the warmer African continent. It has three distinct seasons with onset between March and May, high rainfall between June and August and southward shift from September to October.

- The balance in temperatures on land and in the ocean which drives rainfall during these seasons may get disturbed by the slowing down of the AMOC as the heat transfer from northern hemisphere to the southern hemisphere becomes inefficient and warms up the tropical Atlantic Ocean.

- The greening of the Sahara due to intensification of the WAM can lead to impacts on El Nino, tropical cyclone activity and even the Indian Summer Monsoon rainfall, Francesco SR Pausata, professor of climate science at the University of Quebec, Montreal, Canada.

- The acknowledgement of change in the monsoon’s onset, progress and withdrawal by IMD is a major indication of how India’s primary rainy season is changing its character, mainly owing to global warming.

- This acquires special significance when the impact of the southwest monsoon season on India is taken into account. The season brings in 70 per cent of the annual rainfall received by the country and is responsible for the production of major kharif crops.

- This is because 51 per cent of farmlands in India are still rain-fed and 40 per cent of food production of the country comes from these farmlands, according to the Union Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare.

- Accurate onset dates of the monsoon are crucial information for farmers as they help them decide when to start preparation for sowing their crops.

- If the crops are sowed in time, with decent rainfall, the chances of increased productivity go up and this aspect has ripple effects on the rest of the rural and even the urban economy.

- India is one of the most vulnerable nations to the ravages of climate change, and what makes our experience unique in many ways is that the country faces severe challenges on nearly every climate metric: be it sea level rise, the melting of Himalayan glaciers, an increase in the number of destructive cyclones or extreme heatwaves.

- In many ways, these separate impacts have come together to shape the destiny of one of the most awe-inspiring weather phenomena on the planet, the Indian monsoon.

- Changes in the isotopic composition of foraminifera reflect changes in water salinity, changes in vegetation isotopes gave an indication of changes in vegetation type, reflecting temperature and rainfall amounts, and changes in rubidium reflect changes in sediment input from river runoff.

- The damage that floods cause are a combination of heavy rainfall and man-made activities. Dams along Maharashtra’s Krishna River this year and Kerala’s Periyar river last year were opened around the time when surrounding villages were inundated, further exacerbating the floods.

- Indiscriminate construction in hills and mountains cause landslides. This year’s rainfall in Kerala is not as heavy when compared to last year. “Lots of destruction is because of quarrying.

- Shifting monsoon patterns of the country has resulted in acute water shortage in the nation, with drying up of wells and rivers.

- Major Indian reservoirs runs 10% lower than their normal at any given point of time in the year

- There has been economic loss across agriculture and industry sectors caused by water shortage.

- Cycles of droughts and floods have become more common in many parts of India.

- Water shortage may fuel interstate tensions in India, ex- Cauvery River dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu; Krishna River dispute among Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Telangana;

- Variation in monsoon has also resulted in the incidence of vector borne diseases such as malaria and dengue.

- The government agrees that it needs better policy to cope with the rise in extreme weather events.

- We should have a good policy for water management. Even in agriculture, we should have a policy for sowing suitable crops. This epoch [of lower rainfall] may continue for a few years. So, we should have that kind of strategy.

- Others advocate a radical shift in managing water, calling for a groundwater policy that monitors water extraction. We are approaching water as a commodity and not something which is a living entity.

- The changing pattern of India’s monsoon is a worry, but it is only an added stressor to the pre-existing problems of population growth and haphazard planning.

- Adoption of Renewable and green technology to reduce climate change impact such as e-vehicles.

- Strengthen global forums such as UNFCCC, International Solar Alliance.

- India will need to do more, strengthening the climate resilience of its communities — whether they be rural villages, towns or cities.

- The development of effective policy planning will be especially dependent on scientific models that project scenarios at higher resolutions; at the state, district and local levels.

- The climate change scenarios developed by the Assessment 5 Report of the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) only gives a South Asia-level climate change pathway, which is far too low in resolution to be useful for accurate forecasting.

- State action plans on climate change (SAPCC) were supposed to represent climate change scenarios at least up to the state level. But different states have developed SAPCCs of differing quality.

- Without micro-level projections, mid- and long-term preparation will be difficult. In recent terms, experience has shown again-and-again that preparedness plans are always seen to be lacking or insufficient when disaster strikes.

- Importantly, fine-tuned emergency drills will need to be developed and practiced at the local government level to protect people and property against EWEs.

- If India is able to begin dealing with present-day climate variability effectively, then it will be moving in the right direction to deal with future, intensifying EWE scenarios. As of now, climate change seems to have come knocking early, and there is no way of predicting with precision what path it will take in the coming decades. Preparedness is the best way forward.

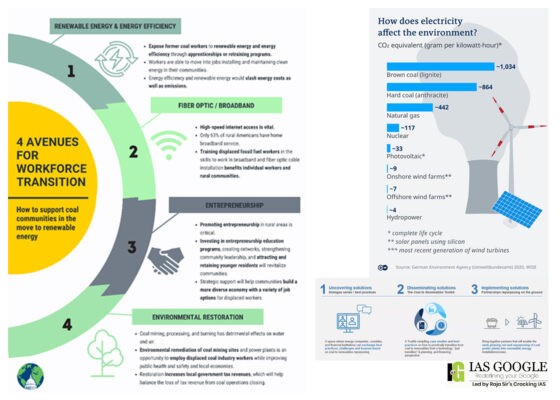

The role of coal in the energy transition

The role of coal in the energy transition

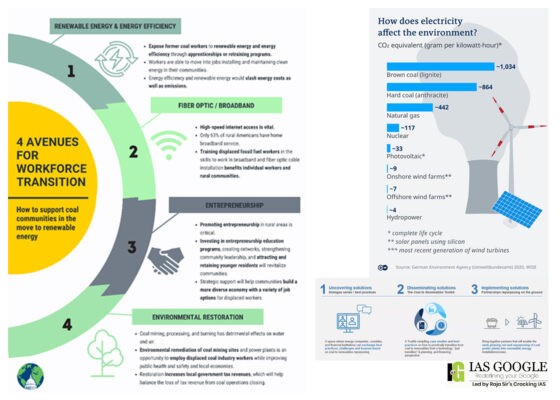

- Today, coal represents 44% of global CO2 emissions and 40% of global installed generation capacity. Of this, 75% is installed in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs), which relies on coal energy for economic development and energy assurance to communities.

- As energy needs rise in EMDEs, plans are in place for a further 500GW of coal capacity to be built in the next 10 to 15 years. At the same time, if the world wishes to stay on track to reach net-zero by 2050, the IEA estimates that all unabated coal must be phased out by 2040.

- The good news is that renewable energy is increasingly cost-competitive. Today, 77% of new renewables' Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is lower than existing coal. By 2030, that share will be 99%.

- The extraction, storage, transportation, and utilization of coal produces fugitive dust, which poses a significant risk to human and animal health, and the environment. Dust generated during extraction presents an occupational hazard for miners and has been linked to pulmonary diseases such as coal workers' pneumoconiosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and silicosis.

- Emissions from coal-fired power plants, especially those without the latest pollution control technology, may contain hazardous air pollutants, exposing individuals to mercury, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, toxic heavy metals (e.g., As, Pb, Cd, Se), radioactive elements (e.g., uranium, radium, thorium), carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds.

- Since the advent of coal mining some 4,000 years ago in China, untold numbers of coal miners have died in cave-ins, floods, explosions and other accidents. Although coal mining is far safer in most countries than it was just a few decades ago, hundreds to thousands of miners lose their lives annually.

- Occupational health impacts include pulmonary diseases such as chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP, “black lung disease”), emphysema, progressive massive fibrosis (PMF), and silicosis.

- Coal has a tendency to combust resulting in uncontrolled fires when exposed to air. These fires can ignite within coal waste piles, storage piles, surface and underground mines. Once ignited underground the coal fires are extremely difficult to extinguish and have resulted in the abandonment of the entire town of Centralia.

- The fires can start from spontaneous combustion, precipitated by machine or human accidents, or intentionally ignited; once ignited, they can persist for years. Coal fires are globally widespread and pose a danger to human and animal populations, as well as the environment, and cause economic hardship by destroying a valuable resource, despoiling the local environment, polluting streams and air.

- Less well known are health outcomes resulting from exposure to coal fire emissions, which release a variety of harmful organic compounds.

- The villagers living within one mile of an active coal fire were 98% more likely to report a range of health issues than villagers living five miles from the fire. However, an even more serious health problem could be the result of the mobilization of potentially toxic elements such as arsenic, selenium and fluorine.

- Perhaps the most dangerous use of coal is in residential settings where coal is burned with little to no ventilation. Globally, approximately 3 billion people use unprocessed solid fuels, including coal, kerosene, and/or biomass (i.e., wood, animal dung, or crop waste), for cooking, often using indoor open fires or inefficient, simple stoves.

- Inefficient combustion of solid fuels, coupled with poor ventilation, exposes individuals (typically women, children, and the elderly) to elevated concentrations of (potentially toxic) air pollutants within the home (e.g., black carbon, carbon monoxide, complex organic compounds, metals, and particulate matter) and also contributes to ambient air pollution once it exists the home.

- Serious health problems have been linked with household cooking using coal, including mental illness, acute respiratory issues in children, lower respiratory infections, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in women, and cataracts.

- Experts estimate that exposure to household air pollution (HAP) generated while cooking with solid fuels is responsible for 2–4 million premature deaths each year, and significantly impacts individuals living in low- and middle-income countries.

- Prior to transportation and utilization (i.e., combustion) - and even before extraction - coal can impact human health. Researchers have suggested that leaching of organic compounds from low-rank coals (lignite, sub-bituminous coal, brown coal) into aquifers that are used for drinking water may contribute to a fatal kidney disease known as Balkan Endemic Nephropathy in Europe and Lignite-Water Syndrome in the U.S.

- The atmosphere has served as a faithful recorder of the transformative consequences to the environment caused by global industrialization and fossil fuel consumption. Of the direct impacts stemming from coal use, the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the most significant, as it serves to amplify the planet's natural greenhouse effect.

- Pre-industrial CO2 levels, determined from analysis of ice cores, are estimated to be around 280 ppmv. In the 1950s, fossil fuel emissions became the dominant contributor of anthropogenic emissions.

- Collectively, the global energy sector contributes more greenhouse gas emissions (73% worldwide) than any other sector; however, coal-fired power generation “continues to be the single largest emitter, accounting for 30% of all energy-related carbon dioxide emissions” and the “single largest source of global temperature increase”.

- Currently, global temperatures are slightly greater than 1 °C above pre-industrial levels. To avoid serious impacts caused by climate change, the consensus is that temperature increases should be limited to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels – while pursuing efforts to restrict global warming to 1.5 °C.

- Global greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut by 50% by 2030, as we aim for zero emissions by 2050. Delayed action in addressing and mitigating global climate change has serious implications for the world's population.

- Direct impacts, many of which we are already experiencing, include increasingly harsh weather conditions, resulting in floods and storms, heat and cold stress, droughts, melting ice sheets, and UV radiation.

- Ecological disruptions will impact human health through vector-, food-, and water-borne diseases and worsening air quality.

- Many of the phases within the coal lifecycle cause land-use change and damage resources. Direct and indirect effects are largely centered around the destruction of the landscape, including agricultural and forested areas, degradation of the physical environment and destruction of wildlife habitats and ecosystems, damage to recreational lands, land subsidence, increased methane emissions (contributing to climate change), sedimentation and erosion.

- Underground mining can trigger collapse and facilitate land subsidence, fundamentally altering the topography. Surface mining drastically alters the land surface through the removal of rock and soil and may lead to erosion and mass wasting.

- Mountaintop removal (MTR) is a form of large-scale surface coal mining that occurs in the steep terrain of Central Appalachia in the United States where other conventional forms of mining are often not practical. MTR involves clear cutting forests and using explosives and large dragline equipment to reach and extract coal. Large valley fills are created between mountain ridges that permanently bury headwater streams.

- All facets of the global water cycle are impacted by coal extraction, processing, transportation, utilization and disposal, and impacts are spatially and temporally extensive. Mining activities directly affect surface and groundwater quality (i.e., contamination), quantity, and availability. Groundwater levels and flow direction may be altered during underground extraction activities, while surface mining typically degrades surface waters through stream runoff.

- Over the long term, these consequences may deplete water resources, and lead to permanent modifications of local and/or regional recharge zones. MTR is particularly damaging to streams as the removal process buries headwater streams. For example, in Kentucky (United States), over 1,400 miles of streams have been buried and/or severely damaged.

- Acid mine discharges (AMD) from (abandoned) underground mines continues to be the most serious water quality and watershed degradation issue for coal mining areas. These outflows significantly increase the health risk to humans through contamination of drinking water sources, ingestion of impacted biota such as fish and mussels, exposure in recreational waters, and the remobilization of heavy metals leached from soils/sediment commonly associated with mining waste.

- Water is a fundamental aspect of coal utilization: all coal plants are dependent on water resources to generate electricity. The usage of significant volumes of water places significant stress on local resources, including regional aquifers.

- It is important to note that impacts are not confined to freshwater environments – marine environments are also affected. The presence of coal dust on the ocean surface and on the seafloor has been documented, causing serious impacts to plants and aquatic biota including localized ocean acidification as compounds within coal dust can react with seawater.

- Conserving, preserving and protecting biodiversity, and the ecological processes and ecosystem services it enables, is essential to long-term sustainability of our planet's resources and human survival. And, after climate change, biodiversity is one of the top two environmental concerns, as reported by the United Nations in their 2019 Global Environment Outlook Report.

- However, despite global re-commitments to reduce biodiversity loss, and the development of strategies, frameworks and environmental policies by many nations to protect biodiversity at a national level, biodiversity continues to diminish at an alarming rate.

- For decades the operational paradigm regarding mining-induced ecosystem impacts has been that any environmental issues resulting from extraction activities are localized, spatially and temporally transient, and easily rectified during site restoration/rehabilitation, when the worked area is returned to the “pre-mining landscape”.

- Land clearance, and associated mining activities and construction, disturbs and displaces wildlife populations as habitats are altered and destroyed. Coal combustion, especially where the latest pollution control technology in not employed, contributes to air pollution, injecting a proverbial “alphabet soup” of harmful compounds into the atmosphere (e.g., heavy metals, mercury, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and others) which are linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases that impact wildlife and human health.

- Coal-fired power plants are also a major contributor of anthropogenic releases of mercury; once deposited onto terrestrial and aquatic surfaces, it is readily transformed and transported in the environment.

- While bioaccumulation and biomagnification within organisms is concerning, the primary consequence is increased vulnerability due to reproductive, neurological and immune problems as organisms develop within a disrupted and stressed environment.

- The transition from coal to renewables isn't just about the LCOE of these technologies, but also about effects on all stakeholders involved.

- This includes the impact on people who are directly employed by coal power plants, people indirectly dependent thereon for employment, and communities built around these.

- Repurposing coal power plants to renewable ones is a key consideration for the just transition. Alongside its social benefits, coal power plant repurposing also presents other advantages and benefits. These include land space, interconnection lines, generators, synchronous condensers, and substations.

- Enel and EDP, for their part, have spent the past decade transitioning from thermal to renewable power. This drive includes committing to the decommissioning of coal power plants.

- Enel has committed to exiting coal completely by 2027, and the remainder of thermal power by 2040. It has also committed to find new life for such plants, aiming to maximize their use as energy providers through repurposing into solar, wind, or green hydrogen sources, storage options, or synchronous compensators.

- Enel's approach to repurposing focuses on cooperation with local stakeholders throughout the process and total retention of all non-retiring employees. Circularity is also a chief concern. Enel aims to reuse as many key components of the coal power plant as possible without creating unnecessary waste.

- Enel's commitment also goes beyond its employees. It's helping suppliers transform their businesses, and retrain their employees to adapt to a transformed operations model.

- In Spain, Enel is repurposing the Teruel coal power plant by replacing an installed capacity of 1,100MW with a large hybrid renewable plant of 1,500MW, including solar, wind and battery storage.

- In Chile it is repurposing the Tarapacá coal power plant into a hybrid project which will have a photovoltaic plant, an energy storage system, and room for salt storage by a third company.

- EDP, meanwhile, is accelerating its energy transition by committing to being coal-free by 2025. It aims to be carbon neutral by 2030 - with 100% renewable energy generation.

- EDP is preparing for the closure of its coal power plants. Its energy transition projects in Portugal, Spain, and Brazil are well underway. In January 2021, EDP closed Sines, Portugal's largest coal power plant and will turn this decommissioned site into a green hydrogen hub.

- EDP's repurposing plans follow a multi-stakeholder approach. Here, government, academia, NGOs, EDP and its suppliers, all work together to ensure the creation of new economic activity in communities. EDP's hydrogen related activities include a green ammonia pilot project, a 100MW green hydrogen production facility, and a collaborative lab to promote hydrogen knowledge exchange.

- Enel and EDP recently presented their stories at the inaugural meeting of the Coal to Renewables initiative, launched by the World Economic Forum.

- This collaboration with Accenture is a unique space where 50+ stakeholders from energy, finance and civil society exchange best practices and seek partnerships to accelerate coal repurposing projects.

- The Initiative allows participants, like Enel and EDP, to share real case studies and the challenges and opportunities faced in the coal to renewables transition. It also has a practical toolkit showcasing technology, finance, just transition and planning case studies. The goal is to create shared understanding and effective partnerships for the just transition.

- Transitioning away from coal is one of the most vital steps we can take to fight climate change. The need for a Just Transition for All to a low carbon economy is an urgent and critical one.

- Phasing out of coal is complex and will take time. Closing mines not only displaces mine workers, but disproportionately impacts workers in related sectors and entire communities in surrounding coal regions. This is particularly true of isolated regions where infrastructure and services are tied to mining. In these communities, mine closure will affect all economic activity.

- Many coal-producing countries lack the resources needed to protect workers and communities, remediate impacted lands, and capitalize on the economic opportunities a transition away from coal makes possible. The prospects for a better future are compelling.

- Low-carbon economies could create over 200 million new net jobs in the next decade in 24 major emerging economies, but policies are needed so the benefits from the green economy are widely shared.

- While the transition will create millions of new jobs in the clean energy sector, many of the coal workers and communities most impacted will struggle to access them. Moreover, cultural, psychological, and other social impacts may have long-lasting effects, particularly in coal regions that already experience extreme inequality and high rates of poverty.

- Pursuing a Just Transition for All will require a whole society approach that considers a broad range of stakeholders, including governments, the private sector, communities, academia, and civil society.

- An integrated approach will help mitigate the impact on people and communities affected by coal transition and create economic opportunities in more sustainable sectors, both locally and beyond.

- Critical measures include social protection policies to minimize the disruption to families and help workers transition into new jobs, and government investment in the green transition – including in education and training, infrastructure, job search and other labour programs, and in community-level interventions.

- The private sector and civil society can bring crucial insights and invaluable additional funding to support the development of viable economic models in challenging settings. Supporting a Just Transition for All also requires early upstream engagement and establishing meaningful partnerships with workers and communities and engaging them in decision making to design solutions for transitioning to regenerative economies and building more inclusive societies.

- The World Bank has decades of experience in supporting countries where coal mines and power plants are closing, wherever they are in the transition process. This includes looking at the interdependencies between the decommissioning of coal assets—such as mining, transport, and power plants—and developing renewable energy programs to take their place. Since 1995, we have provided more than $3 billion to support coal transitions.

- As part of our Climate Change Action Plan 2021-25, we have doubled down on our commitment to helping countries accelerate the transition away from coal while protecting workers, investing in communities, and protecting the environment.

- The World Bank has built an approach based on lessons from decades of transition experience, and leveraged this approach to help national, regional, and local authorities around the world develop clear roadmaps for a Just Transition for All.

- In every engagement, our assistance helps to build governance structures, support the engagement and welfare of impacted workers and communities, and remediate and repurpose former mining lands and coal-fired power plants.

- We continue to learn and update our approach to enhance how we address the social and environmental impacts of the transition and how we support community participation in decision making.

- Efforts to manage transitions from coal in other emerging markets and developing economies are largely being facilitated by DFIs, which are designing targeted packages.

- In all cases, early planning and social dialogue with affected stakeholders is critical. The multiplicity of government actors involved in local economic development, energy and environmental management makes planning challenging, especially in emerging market and developing economies, and the establishment of special purpose entities might be necessary to pool various funding sources and manage disbursements on the ground.

- There is an important role for blended finance, along with carbon pricing, in accelerating the closure of coal power plants and increasing investment in clean energy. The early involvement of banks and other investors is critical to deal with potential external financial exposures.

- Managing social and environmental impacts calls for dedicated and long-term local focus and financing, especially in the most challenging instances where whole towns and communities have been heavily reliant on the coal industry for employment and income.

- International efforts are focusing on ways to separate coal assets into new financing and ownership structures, while creating economic opportunities for workers and communities.

- The Asian Development Bank is carrying out a feasibility study with potential host countries in Southeast Asia (initially Indonesia, Philippines and Viet Nam) on the Energy Transition Mechanism, a platform to accelerate the retirement of coal power using blended finance and to support investment in renewables, all in an equitable, scalable and market-based manner.

- The World Bank is supporting long-term transitions for coal regions through institutional governance reforms, assistance to communities and repurposing of land and assets.

Key Findings

Key Findings

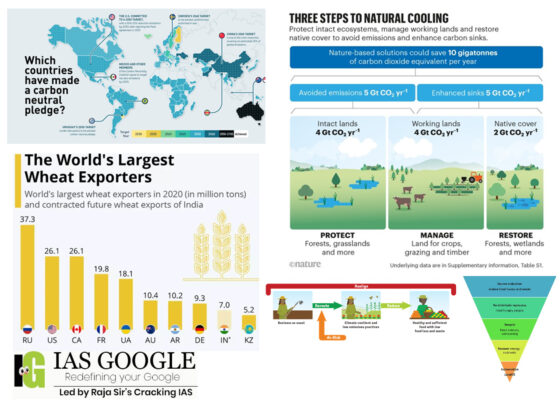

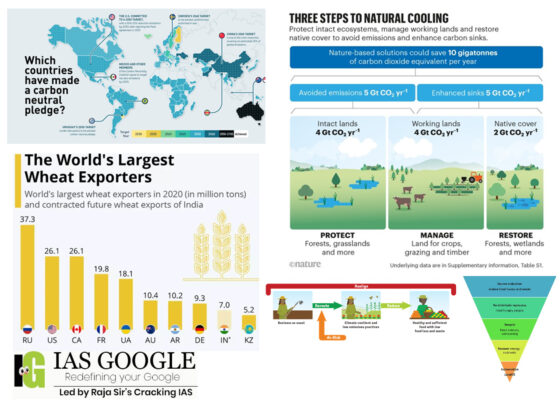

- The food and agriculture sector can lead the world on the path to net zero, despite facing uncertainty, but it must be on the agenda at COP27 - and we have to act now.

- This was the overwhelming consensus of an expert panel for the opening plenary of the World Economic Forum's 'Bold Actions for Food' event.

- Food systems account for up to one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions and are failing 768 million people living in hunger.

- In the face of global shocks from the war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic and extreme weather events, it has become more urgent than ever to transition food systems to a net-zero, nature-positive infrastructure that feeds everyone.

- Today’s food systems do not provide the world’s population with enough nutritious food in an environmentally sustainable way.

- Nearly 800 million people are undernourished, 2 billion are considered micronutrient-deficient and an additional 2 billion are overweight or obese. Meanwhile, food production, transport, processing and waste are placing enormous pressure on environmental resources.

- In 2020, the pandemic caused an increase in world hunger, with as many as 811 million people going hungry globally, according to the FAO and Forum’s white paper Transforming Food Systems: Pathways for Country-led Innovation.

- More than 3 billion people cannot afford a healthy diet, and more than 1.5 billion people cannot afford a diet with even the minimum level of essential nutrients.

- There’s also a gender disparity in terms of food insecurity - with women 10% more likely than men to be moderately or severely food insecure.

- And while people don’t have enough to eat, food systems are gradually contributing to climate change, emitting up to one-third of global greenhouse gases.

- Globally they contribute to 80% of tropical deforestation and are a main driver of soil degradation and desertification, water scarcity and biodiversity decline.

- We've faced two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, and have stepped up on the climate agenda strongly, but now we’re facing a war with "massive implications" for migration, economic fall-out and for the food security of hundreds of millions of people.

- Prices are shooting up and more than ever it shows how exposed our food systems are globally. Russia and Ukraine account for almost 30% of international sales of wheat.

- Russia is the largest exporter of wheat, and because of poor harvest and supply chain issues, global stocks are already low. It also impacts edible oils: 50% of sunflower oil is exported by Ukraine.

- Wheat prices have increased by 53% over the last couple of months and it's impacting Egypt and Indonesia most as the biggest importers of wheat from Russia, along with other African countries: "There will be massive disruptions."

- The effects on the global food supply will be long-lasting and how serious this will become will depend on what kind of policies countries put in place in the next few weeks.

- This is one of the most urgent and immediate things that everyone needs to have a conversation around, because we are already seeing countries do the things that are detrimental to lowering prices and helping those affected.

- Wheat prices in the international market have hit record highs since Russia’s military strikes in Ukraine started as it has cut global wheat exports by 30%.

- The spike in wheat prices in international market due to the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war may bring some benefit to Indian farmers in terms of getting a good price for their produce and the government may have to procure less quantity of the foodgrain at assured price (MSP) as private players would buy more directly from farmers.

- Less procurement by the government would reduce the subsidy burden as well.

- further firming up of wheat prices will result in an increase in its export from India.

- It helps the exporters to ship out their stock made from their own procurement once they buy the FCI grain for domestic requirement.

- There is a high possibility that private players would directly buy from farmers in big quantities during the coming harvesting season, particularly in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan where best quality wheat is produced.

- This will also have an overall impact on the total procurement target and if the current condition continues, we may end up procurement target and if the current condition continues, we may end up procuring around 350 to 360 lakh tonnes during the next crop season against the target of 440 lakh tonnes.

- India is the only major global supplier of wheat at this point, thanks to massive surplus stocks at home.

- The rally in global prices and a record slump in the Indian rupee against the dollar also make wheat shipments attractive to Indian sellers.

- Indian warehouses are brimming with wheat after five consecutive record harvests - largely a result of favourable weather, the introduction of high-yielding seed varieties and state-set support prices for growers.

- Wheat harvests will again scale new peaks in 2022, with farmers set to harvest 111.32 million tonnes from next month, up from the previous year's 109.59 million.

- Overflowing grain bins often force the Food Corporation of India - the government-backed grains stockpiler - to store wheat in temporary sheds.

- Wheat stocks at government warehouses total 28.27 million tonnes against a target of 13.8 million tonnes. With another bin-bursting harvest kicking in from April, granaries will overflow from May and June.

- Bulging wheat stocks helped the government cushion the blow from droughts in 2014 and 2015 and enabled Prime Minister's administration to distribute free grain during coronavirus lockdowns.

- But economists say maintaining such a large, unproductive inventory of wheat unnecessarily strains stretched state finances, and the monoculture also saps the soil of nutrients.

- India has struggled to export wheat due to the annual increase in support or guaranteed prices offered by the government to growers. That increase made Indian wheat more expensive than world prices, making overseas sales uneconomic.

- But the rare confluence of multi-year high global wheat prices, a record low rupee and a surge in demand from traders seeking to replace Russian and Ukrainian wheat with the Indian variety has made shipments from India attractive.

- Robust demand from Asian buyers such as Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and the Philippines allows India to supply wheat at lower freight rates.

- India can also supply wheat to the Middle East at lower freight costs than many other sellers.

- Also, of late India has been able to dispel concerns about the quality of its wheat as Indian scientists have introduced many high-protein varieties suitable for pasta and pizza dough.

- Indian traders and government officials also cite an increase in cargo handling capacity at Indian ports as another help.

- But traders say an increase in internal freight costs to transport grain from major wheat-producing states to ports, and a potential shortage of railway wagons, could impede exports.

- This means starting with practices, such as agroecology and regenerative farming, which aim to care for the soil and shun the use of synthetic, chemical-based fertilizers and pesticides.

- These techniques reduce fossil fuel use on farms and boost the potential of soil to store more carbon.

- Synthetic fertilizers accounted for about 1,000 out of 7,145 metric tons of global on-farm GHG emissions in 2018, making it the second biggest emitter after livestock, according to a recent paper published in Environmental Research Letters by scientists from the UN, NASA, the International Energy Agency (IEA), and other institutions.

- But Woodward claims that the UK government, which is hosting the next round of UN climate negotiations, is ignoring farming’s impact on climate change – as well as its potential for mitigation. He said he’d like future farm subsidies to go towards helping farmers transition to agroecology, and to ‘green recovery’ funds to integrate trees into farming systems.

- Similarly, Environmental Entrepreneurs (E2), wants the country’s Department of Agriculture to incentivize farmers to take up regenerative agriculture by ensuring the price of crop insurance reflects the lower risk of crop failure in farms adopting it.

- It has been suggested that corn, soybean, and almond farmers using these techniques have seen their incomes increase from higher yields and savings on inputs. But the biggest potential comes from sequestering carbon into the soil – carbon that farmers can be paid for by third parties seeking to offset their own emissions.

- While debate continues as to whether this potential windfall is realistic or an overestimate, a recent E2 report states that US growers could sequester the equivalent of the annual emissions of 64 coal-fired power plants into the soil if they adopt regenerative farming methods.

- Regenerative age is also a key political tool to get large swathes of the US involved in solving climate change, Lederer adds. She points out that the 2018 Farm Bill, which included incentives to sequester carbon, was passed by Congress with bipartisan support – making it something of a rarity in recent US political history.

- However, for farming to have a major impact on bringing down emissions it will be required to address the elephant (or cow) in the room: livestock.

- This is why the new generation of alternative proteins will play a crucial role in food systems’ ‘net zero’ ambitions, says Emma Ignaszewski, corporate engagement project manager at the Good Food Institute (GFI.)

- Meat consumption per capita is at an all-time high and education for behaviour change won’t solve this problem on its own, but alt-proteins can tackle several problems at once, including climate change, antibiotic resistance, global hunger, and deforestation.

- Two new GFI-commissioned papers say plant-based meat analogues have a significantly lower carbon footprint than animal-derived proteins.

- Cell-cultured meat doesn’t score quite so well due to the level of energy consumption currently required to produce it. However, if only renewable energy is used, these products would have a carbon footprint 17% lower than conventionally reared chicken meat, 52% lower than pork, and up to 92% lower than beef.

- Energy mix is only one aspect of the whole value chain, says Synthesis’ Welch, who previously worked as director of science and technology at GFI.

- Very few companies in the alternative protein space are talking about ‘net zero’ in a detailed way. As these companies mature and start to look for exits, they’re going to need to do this in a lot more detail, adding that creating crops designed specifically for producing alt-proteins is an area “ripe for disruption.”

- Companies such as Equinom and Benson Hill, for example, are developing crop varieties with a higher density of protein. This means they require less processing, which tends to be water and energy-intensive, to turn them into ingredients for the final product.

- Welch is also excited by companies using fermentation to produce alt-proteins. Fermentation is adaptable to all types of environments and economies, and is likely to have fewer constraints when scaling in different communities, he adds.

- Shifting diets would also stop the conversion of natural ecosystems to farmland or pastures. Between 1990 and 2018, this was the largest single emissions source in the food system, the authors of the aforementioned Environmental Research Letters paper say.

- In Latin America and the Caribbean, land use change is the single biggest source of GHG emissions across all sectors, according to Initiative20x20, which aims to protect and restore 50 million hectares of land by 2030.

- Rapid agricultural expansion, driven by market demand for beef and crops such as coffee and sugarcane, is threatening the region’s forest cove

- The narrative is that restoring forests is good because it produces oxygen and captures carbon, but the market doesn’t value those things.

- It persuades plantation owners to restore forests on some of their land because it can reduce losses from seasonal flooding. The carbon sequestration potential is significant too.

- We need to address the long-term problems as well as focusing on the immediate ones.

- Climate is a pressing problem, and the food system is decades behind in its decarbonization efforts compared to the energy sector. We’re not spending the resources to break down the components. The technologies are out there, but we need to utilize them.

- There are three things the food and agriculture sector need to accelerate the shift to net zero: "We need to welcome and nurture innovation and science, collaborate with other sectors and act now.

- We need to include farmers in the equation, they’re part of the solution, we need to bring them to the table. It’s complex, you’re dealing with small farmers and helping them to transform the system is crucial.

- Government agricultural subsidies can support farmers to "do food production the right way.

- Shifting and scaling up subsidies should be discussed at COP27 because "it’s a huge amount of public money that’s not only wasted, it’s actually detrimental. You can produce the same amount of rice and cut emissions in half."

- Energy people understand, they see a smoke stack and know they need to change it, it’s clear it needs to go away – but with agriculture, people don’t see and feel what’s wrong.

- Subsidies and Technologies are Crucial. There’s still a bunch of stuff we need to invent, so we need to invest in innovation for a purpose.

- We have to be clearer to politicians to get a stronger commitment, scientists have designed a pragmatic approach to address these issues.

- We should support the UN secretary-general to end the war and restore peace. Future COP meetings have got to focus on food and agriculture to help us get our arms around the climate challenge we face.

- It has been outlined that the US' billion-dollar Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities opportunity for pilot projects that create market opportunities for commodities produced using climate-smart practices.

- Its aim is to get the consumer engaged through knowing if products were produced through climate-smart and regenerative practices, develop and use measurement tools to track carbon reduction and sequestration and establish a standard to market 'climate-smart' commodities.

- We have to commit to local and low-cost food systems to reduce the mileage of food travel from farm to fork. We want to create more competition and invest in more robust, resilient systems, this involves providing resources and technology assistance, and developing food hubs for smaller operations to market more effectively.

- There’s an awful lot going on in this space, there’s a tipping point we’re reaching in terms of the need for agriculture to be a leader in this space.

- The World Economic Forum is looking for organizations that want to contribute to our efforts to improve food security and build inclusive, healthy, efficient and sustainable food systems.

- Two billion people in the world currently suffer from malnutrition and according to some estimates, we need 60% more food to feed the global population by 2050.

- Yet the agricultural sector is ill-equipped to meet this demand: 700 millions of its workers currently live in poverty, and it is already responsible for 70% of the world’s water consumption and 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- New technologies could help our food systems become more sustainable and efficient, but unfortunately the agricultural sector has fallen behind other sectors in terms of technology adoption.

- Launched in 2018, the Forum’s Innovation with a Purpose Platform is a large-scale partnership that facilitates the adoption of new technologies and other innovations to transform the way we produce, distribute and consume our food.

- With research, increasing investments in new agriculture technologies and the integration of local and regional initiatives aimed at enhancing food security, the platform is working with over 50 partner institutions and 1,000 leaders around the world to leverage emerging technologies to make our food systems more sustainable, inclusive and efficient.

- At the Food Systems Summit, UN Secretary-General António Guterres created an Innovation Lever of Change to bring together the public, private and social sectors on innovation.

- The Innovation Lever, whose work has led to the white paper, called for countries to set a target to invest 1% of their food system-related GDP in innovation.

- Over the next 10 years, investing in innovation could end hunger, significantly cut global emissions and generate more than $1 trillion in economic returns.

- Currently only 7% of the annual funding for agricultural innovation for the Global South contains sustainability goals. If that figure were 50%, it could contribute an additional $30 billion towards transforming food systems.

- At the same time, there is a $15.2 billion funding gap for food system innovation that could support ending hunger, keeping emissions within 2°C and reducing water use by 10%.

- Improving soil management techniques could offset and sequester about 20% of total annual emissions.

- By 2030, enhanced connectivity in agriculture could add more than $500 billion to global gross domestic product, according to McKinsey research.

- Meanwhile, biological innovation in the fields of agriculture, aquaculture and food production could generate economic returns of up to $1.2 trillion over the next 10-20 years, according to the white paper.

- Zero hunger – providing humanitarian aid and keeping the free flow of goods around the world.

- Regenerative agriculture to get to net zero, with Knorr launching eight new large projects this year.

- Plant-based food, which involves encouraging the consumer to change their diet to eat less meat.

- Food waste reduction, which also involves the consumer. The world wastes a third of all the food it produces. "We’re using way too much land and producing greenhouse gases to produce all that food we don’t end up using."

- Health – making products healthier.

- The consumer's role is vital. We have to learn from energy transformation. Food is more complicated because we’re working with different animals and plants and in different environments.

- We’re entering an age of volatility, that’s the norm, so of course you have to bring in the consumer, the food companies can’t do it in isolation. We have to take a holistic approach.

- Every food company has to be transparent in the accounting of their carbon footprint and start to reduce their emissions, so consumers can choose who they support.

- Scope 3 emissions account for 80-90% of emissions, so those must be included in reporting too, admitting there are "still problems around measurement".

- There’s lots of work to be done", but we have an opportunity to pay farmers to do the right thing through subsidies and incentivizing brands to sequester carbon.

- The FAO and Forum’s roadmap sets out principles and actions to accelerate innovation, firmly embedded in the need to be holistic and inclusive.

- Protects and respects the right of all stakeholders, particularly the most vulnerable and those on the cusp, to participate fairly in decision-making about food systems

- Has positive social and environmental impacts by adopting nature-positive and sustainable approaches while ensuring equitable livelihoods

- Ethically develops digital tools, technologies and data platforms that include last-mile solutions for farmers and all consumers in food systems.

- This includes developing strategies to encourage collaboration between government departments, reviewing regulation that prevents the scaling up of agricultural innovation, and creating multi-stakeholder Food Innovation Hubs to link universities, NGOs, (local) governments, start-ups, mid to large companies and venture capital.

- Among the countries already leading the way with food hubs are Viet Nam - which aims to make the whole journey from farm to plate sustainable - and the Netherlands, which is hosting the Food Innovation Hubs’ Global Coordinating Secretariat.

- With an emphasis on promoting collaboration and inclusivity, this includes developing common and agreed-upon food-related policies that protect the rights of all stakeholders – from small-scale producers and community-based organizations to women and indigenous peoples.

- The Innovation Lever identified the 100 million Farmers platform as a way to incentivize farmers and enable consumers to put climate, nature and resilience at the core of the food economy to boost nature-positive production, advance equitable livelihoods and build resilience to vulnerabilities, shock and stress. You can read more about the platform’s work here.

- This includes making sure data and digital systems are aligned, agile and interoperable and can support a climate-smart and inclusive food systems transformation.

- The Innovation Lever identified the Global Coalition for Digital Food Systems made up of three delivery platforms (One Map, Data and Digital Marketplace Playbook and Digital Data Cornucopia), as a coalition with the capability to support countries to employ data in inclusive and responsible ways, to create visible opportunities within food systems.

Genesis

Genesis

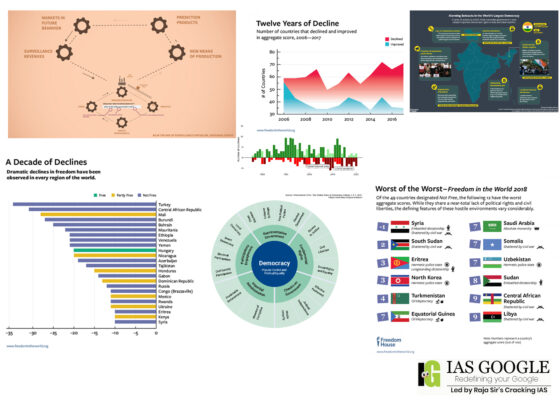

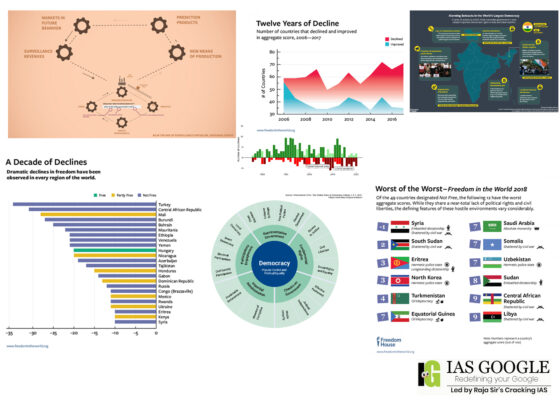

- The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 was followed by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Together, they brought the Cold War to an end and sounded the death knell of dictatorial regimes in Eastern Europe.

- The impact of these events was dramatic. They hastened a wave of democratisation, not merely in Eastern Europe, but across continents—in the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia.

- The share of free countries grew from 36 to 46 percent between 1988–2005.

- Unfortunately, post 2005, year after year, a worrying decline in global freedom has been recorded by the most prominent global democratic surveys.

- Surveillance capitalism describes a market driven process where the commodity for sale is your personal data, and the capture and production of this data relies on mass surveillance of the internet. This activity is often carried out by companies that provide us with free online services, such as search engines (Google) and social media platforms (Facebook).

- These companies collect and scrutinise our online behaviours (likes, dislikes, searches, social networks, purchases) to produce data that can be further used for commercial purposes. And it’s often done without us understanding the full extent of the surveillance.

- The term surveillance capitalism was coined by academic Shoshana Zuboff in 2014. She suggests that surveillance capitalism depends on the global architecture of computer mediation which produces a distributed and mostly uncontested new expression of power that I christen: “Big Other”.

- The late 20th century has seen our economy move away from mass production lines in factories to become progressively more reliant on knowledge. Surveillance capitalism, on the other hand, uses a business model based on the digital world, and is reliant on “big data” to make money.

- The data used in this process is often collected from the same groups of people who will ultimately be their targets. For instance, Google collects personal online data to target us with ads, and Facebook is likely selling our data to organisations who want us to vote for them or to vaccinate our babies.

- Third-party data brokers, as opposed to companies that hold the data like Google or Facebook, are also on-selling our data. These companies buy data from a variety of sources, collate information about individuals or groups of individuals, then sell it.

- Smaller companies are also cashing in on this. Last year, HealthEngine, a medical appointment booking app, was found to be sharing clients’ personal information with Perth lawyers particularly interested in workplace injuries or vehicle accidents.

- Surveillance capitalism practices were first consolidated at Google. They used data extraction procedures and packaged users’ data to create new markets for this commodity.

- Currently, the biggest “Big Other” actors are Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple. Together, they collect and control unparalleled quantities of data about our behaviours, which they turn into products and services.

- This has resulted in astonishing business growth for these companies. Indeed, Amazon, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Apple and Facebook are now ranked in the top six of the world’s biggest companies by market capitalisation.

- Google, for instance, processes an average of 40,000 searches per second, 3.5 billion per day and 1.2 trillion per year. Its parent company, Alphabet, was recently valued at US$822 billion.

- Newly available data sources have dramatically increased the quantity and variety of data available. Our expanding sensor-based society now includes wearables, smart home devices, drones, connected toys and automated travel. Sensors such as microphones, cameras, accelerometers, and temperature and motion sensors add to an ever-expanding list of our activities (data) that can be collected and commodified.

- Commonly used wearables like smart watches and fitness trackers, for example, are becoming part of everyday health care practices. Our activities and biometric data can be stored and used to interpret our health and fitness status.

- This same data is of great value to health insurance providers. In the US, some insurance providers require a data feed from the policyholder’s device in order to qualify for insurance cover.

- Connected toys are another rapidly growing market niche associated with surveillance capitalism. There are educational benefits from children playing with these toys, as well as the possibility of drawing children away from screens towards more physical, interactive and social play. But major data breaches around these toys have already occurred, marking childrens’ data as another valuable commodity.

- There were alarming setbacks in political rights and civil liberties in a number of countries. Strikingly, countries that witnessed the largest declines in freedom were not restricted to a specific area but were spread across continents.

- Even more alarming was the fact that robust, long-standing democracies were shaken by an undercurrent of populist political forces challenging established fundamentals of democratic governance.

- These developments brought cheer to dictatorships. They strove to highlight, what was in their opinion, the innate weaknesses of democracy and emboldened them to crush internal dissent and lend support to the rise of dictatorial regimes beyond their borders.

- Distressed by the results of these global surveys that discerned a regression in democratic governance in several democracies around the globe, prominent authors and thinkers from the western world have attempted to identify causes and have offered ideas to fix this alarming trend in democratic decline.

- Amongst the most significant causes for ‘democratic recession’ that these thinkers listed was what was termed as ‘surveillance capitalism’. Surveillance capitalism giants such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple controlled every aspect of human information and communication systems in most parts of the world. And yet, they were substantially beyond any accountability to the legal system of nations.

- It was evident that a surveillance society that they spawned was quite detrimental to the advancement of democratic values. Further, the fall in percentages in white populations in the West, in turn fueling large-scale non-white in-migration, was stoking the fires of polarisation in the western society along racist lines.

- The internet and social media played a significant and sinister role in stoking the fires of divisiveness, and this was unfortunately breaking down the idea of inclusive citizenship. Furthermore, the current set of global institutions such as the United Nations (UN), set up to uphold a global democratic order, had been found seriously wanting and were unable to protect democratic values.

- In the face of such impotence, there has been a growing display of audacity by dictatorial regimes in meddling with democratic processes such as elections, coercion of public officials, and attempts at poaching struggling democracies through predatory investments.

- There has also been growing inequality in democracies and disenchantment amongst the youth with messy decision-making processes witnessed in democracies. The speed with which autocracies could implement decisions has engendered admiration of socialism amongst younger generations in the democratic world.

- The past year provided ample evidence that undemocratic rule itself can be catastrophic for regional and global stability, with or without active interference from major powers like Russia and China.

- In Myanmar, the politically dominant military conducted a brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Muslim Rohingya minority, enabled by diplomatic cover from China and an impotent response from the rest of the international community.

- Some 600,000 people have been pushed out, while thousands of others are thought to have been killed. The refugees have strained the resources of an already fragile Bangladesh, and Islamist militants have sought to adopt the Rohingya cause as a new rallying point for violent struggle.

- Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan broadened and intensified the crackdown on his perceived opponents that began after a failed 2016 coup attempt. In addition to its dire consequences for detained Turkish citizens, shuttered media outlets, and seized businesses, the chaotic purge has become intertwined with an offensive against the Kurdish minority, which in turn has fuelled Turkey’s diplomatic and military interventions in neighbouring Syria and Iraq.

- Elsewhere in the Middle East, authoritarian rulers in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt asserted their interests in reckless ways that perpetuated long-running conflicts in Libya and Yemen and initiated a sudden attempt to blockade Qatar, a hub of international trade and transportation.

- Their similarly repressive arch-rival, Iran, played its own part in the region’s conflicts, overseeing militia networks that stretched from Lebanon to Afghanistan.

- Promises of reform from a powerful new crown prince in Saudi Arabia added an unexpected variable in a region that has long resisted greater openness, though his nascent social and economic changes were accompanied by hundreds of arbitrary arrests and aggressive moves against potential rivals, and he showed no inclination to open the political system.

- rising inequalities, declining social mobility, disenfranchisement, growing anxiety with rapid societal change, as well as cross-border challenges, are fuelling political dissatisfaction in many countries. In 2021, less than half of citizens trusted their government. The decrease in public trust hinders policy making and governments’ ability to address social and economic challenges, thus further increasing dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracies.

- Recent years in many OECD countries have been characterised by low voter turnout, greater political polarisation and a growing number of people dissociating themselves from traditional democratic processes, and citizens expressing their discontent through new forms of protest.

- The OECD is committed to the values of democracy, the rule of law, and the defence of human rights. At the OECD Meeting of the Council at Ministerial Level, 2021, Members expressed “the need to guard against threats to democracy”.

- In the context of global concerns about the health of democracies, it would be germane to look at the dangers that bedevil Indian democracy. Many of the dangers globally faced by democracies in the world are in some measure also threats to this country.

- The Government of India’s recent run-ins with global communication organisations are a case in point. In the face of challenges faced by the Indian communication system, India’s laws definitely need a serious relook, overhaul, and tightening.

- There is no doubt that greater responsibility needs to be injected into the use of social media. A lot of work also needs to be done in terms of inclusive citizenship.

- The variety of India’s social issues are unmatched by any country. Some of them have been left unattended for a long time. It would be important that they get settled over an identified period of time and not allowed to fester.

- The sad situation gets aided by the slow judicial process, huge pendency of cases and weak legislation surrounding the conviction and debarring of public representatives from fighting elections.

- Further unsavoury developments internal to the country are of immediate significance. Their impact on the nation’s democracy is worrisome. The first is the criminalisation of politics. It has been reported that nearly 50 percent MPs in the current Lok Sabha have criminal records.

- This marks an increase of 44 percent in the number of MPs with declared criminal cases since 2009. Even more alarming was the report of the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) revealing that 76 of the 543 MPs of the Lok Sabha in 2009 had been charged with serious offences such as murder, rape, and dacoity. The situation in many state assemblies is no better.

- This is a dangerous trend, since criminalisation of politics cuts people off from any meaningful engagement with their representatives, adds to their growing disillusionment with democracy, and hits the core of good democratic governance.

- The sad situation gets aided by the slow judicial process, huge pendency of cases and weak legislation surrounding the conviction and debarring of public representatives from fighting elections.

- The second is the increasing disinterest of elected representatives in performing their primary function of spending quality time in the Parliament and State Assemblies. It is expected that they would study and speak on issues that hold great significance for the country and the states.

- Equal attention ought to be given by them to deliberate on bills while drafting them Unfortunately, it has been found that state legislative assemblies averaged a mere 30 sittings annually over the last decade, with Punjab, Haryana, and Delhi being the biggest culprits, followed by Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and Uttar Pradesh.

- Lok Sabha’s record was not too bright either. It averaged only 63 seats per year in the last 10 years. Clearly, any debate on laws is not receiving the kind of attention they deserve.

- As a consequence, quality of statutes has eroded, a factor which the Chief Justice of India has referred to in his observations. This indicates a decline in the quality of Indian democracy that does not bode well. Along with some of the global concerns raised, India needs to work on its internal weaknesses to protect the quality of its democracy.

- In looking for solutions, the authors warn that any disjointed effort by individual democratic nations to stem the undemocratic tide may not suffice.

- The contest must be determined and united, so that if one country comes under attack from a dictatorial regime, the democratic world ought to rally with punitive action to deter the assailant and cushion the country under attack with positive assistance in order that it may stand on its own legs.

- Additionally, countries need to overhaul their legal systems by rewriting laws so that countries may end the corporate control of information flows.

- They also should be able to enforce a radical transparency in politics and business, and enforce them with vigour.

- The authors warn that if the western democratic world is not keen to disallow corrupt money flows, democracies would continue to suffer.

- Liberal democracies must ensure through policies that economic prosperity reaches more of their citizens and social respect is broad-based.

- Democracies also need to stamp out the commercial market for intelligence grade software and other technologies that promote spy and hacking systems, and threaten privacy and freedom.

- They cannot allow companies in democratic countries to be key enablers of tyranny.

- The growing turnout of women voters could influence political parties’ programmatic priorities and improve their responsiveness to women voters’ interests, preferences, and concerns, including sexual harassment and gender-based violence.

- The extent to which parties represent women and take up their interests is closely tied to the health and vitality of democratic processes. However, the strength of civil society initiatives is not entirely dependent on the strength of political institutions.

- At this crucial juncture, to cherish our democratic values, we will need to sympathise with the voice of the 15th century Bengali poet, Ramoni, a low-caste washerwoman, who sang, “I’ll not stay any longer in this land of injustice/ I’ll go to a place where there are no hellhounds”.

Genesis

Genesis

- The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated many low- and middle-income countries, causing widespread food insecurity and a sharp decline in living standards.

- In response to this crisis, governments and humanitarian organizations worldwide have distributed social assistance to more than 1.5 billion people. Targeting is a central challenge in administering these programmes: it remains a difficult task to rapidly identify those with the greatest need given available data.

- Our approach uses traditional survey data to train machine-learning algorithms to recognize patterns of poverty in mobile phone data; the trained algorithms can then prioritize aid to the poorest mobile subscribers.

- Evaluating the approach by studying a flagship emergency cash transfer program in Togo, which used these algorithms to disburse millions of US dollars' worth of COVID-19 relief aid.

- Our analysis compares outcomes—including exclusion errors, total social welfare and measures of fairness—under different targeting regimes. Relative to the geographic targeting options considered by the Government of Togo, the machine-learning approach reduces errors of exclusion by 4–21%.

- Relative to methods requiring a comprehensive social registry, the machine-learning approach increases exclusion errors by 9–35%. These results highlight the potential for new data sources to complement traditional methods for targeting humanitarian assistance, particularly in crisis settings in which traditional data are missing or out of date.

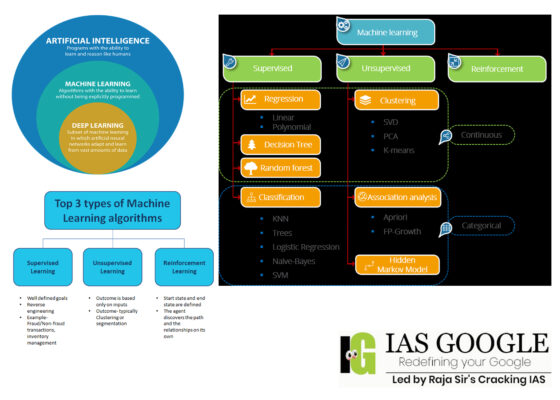

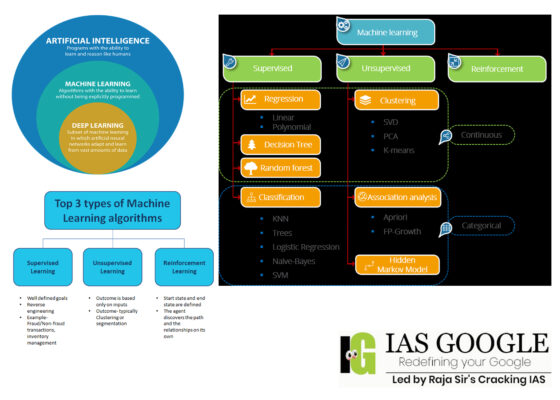

- Machine learning (ML) is a type of artificial intelligence (AI) that allows software applications to become more accurate at predicting outcomes without being explicitly programmed to do so. Machine learning algorithms use historical data as input to predict new output values.

- Why is Machine Learning Important?

- Machine learning is important because it gives enterprises a view of trends in customer behavior and business operational patterns, as well as supporting the development of new products.

- Many of today's leading companies, such as Facebook, Google and Uber, make machine learning a central part of their operations.

- Machine learning has become a significant competitive differentiator for many companies.

- It is often categorized by how an algorithm learns to become more accurate in its predictions. There are four basic approaches: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, semi-supervised learning and reinforcement learning. The type of algorithm data scientists chooses to use depends on what type of data they want to predict.

- In this type of machine learning, data scientists supply algorithms with labeled training data and define the variables they want the algorithm to assess for correlations. Both the input and the output of the algorithm are specified.

- This type of machine learning involves algorithms that train on unlabeled data. The algorithm scans through data sets looking for any meaningful connection. The data that algorithms train on as well as the predictions or recommendations they output are predetermined.

- This approach to machine learning involves a mix of the two preceding types. Data scientists may feed an algorithm mostly labeled training data, but the model is free to explore the data on its own and develop its own understanding of the data set.

- Data scientists typically use reinforcement learning to teach a machine to complete a multi-step process for which there are clearly defined rules. Data scientists program an algorithm to complete a task and give it positive or negative cues as it works out how to complete a task. But for the most part, the algorithm decides on its own what steps to take along the way.

- Supervised machine learning requires the data scientist to train the algorithm with both labelled inputs and desired outputs. Supervised learning algorithms are good for the following tasks:

- Binary classification: Dividing data into two categories.

- Multi-class classification: Choosing between more than two types of answers.

- Regression modelling: Predicting continuous values.

- Ensembling: Combining the predictions of multiple machine learning models to produce an accurate prediction.

- Unsupervised machine learning algorithms do not require data to be labelled. They sift through unlabelled data to look for patterns that can be used to group data points into subsets. Most types of deep learning, including neural networks, are unsupervised algorithms. Unsupervised learning algorithms are good for the following tasks:

- Clustering: Splitting the dataset into groups based on similarity.

- Anomaly detection: Identifying unusual data points in a data set.

- Association mining: Identifying sets of items in a data set that frequently occur together.

- Dimensionality reduction: Reducing the number of variables in a data set.

- Today, machine learning is used in a wide range of applications. Perhaps one of the most well-known examples of machine learning in action is the recommendation engine that powers Facebook's news feed.

- Facebook uses machine learning to personalize how each member's feed is delivered. If a member frequently stops reading a particular group's posts, the recommendation engine will start to show more of that group's activity earlier in the feed.

- Behind the scenes, the engine is attempting to reinforce known patterns in the member's online behavior. In addition to recommendation engines, other uses for machine learning include the following:

- Customer relationship management. CRM software can use machine learning models to analyze email and prompt sales team members to respond to the most important messages first. More advanced systems can even recommend potentially effective responses.

- Business intelligence. BI and analytics vendors use machine learning in their software to identify potentially important data points, patterns of data points and anomalies.

- Human resource information systems. HRIS systems can use machine learning models to filter through applications and identify the best candidates for an open position.

- Self-driving cars. Machine learning algorithms can even make it possible for a semi-autonomous car to recognize a partially visible object and alert the driver.

- Virtual assistants. Smart assistants typically combine supervised and unsupervised machine learning models to interpret natural speech and supply context.