- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

The role, significance of film certification tribunal, now abolished

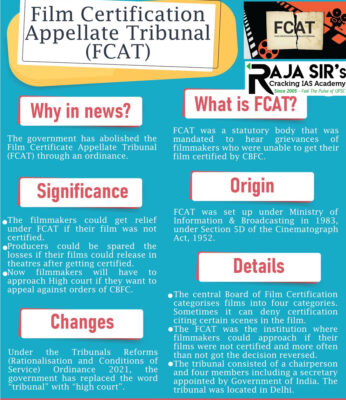

The story so far: On April 4, the Centre notified the Tribunals Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance, 2021, issued by the Ministry of Law and Justice. The Tribunals Reforms Bill was introduced in the Lok Sabha in February, but was not taken up for consideration in the last session of Parliament. The President later issued the ordinance, which scraps the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT), a statutory body that had been set up to hear appeals of filmmakers against decisions of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC), and transfers its function to other existing judicial bodies. Eight other appellate authorities have also been disbanded with immediate effect. The ordinance has amended The Cinematograph Act, 1952, and replaced the word ‘Tribunal’ with ‘High Court’.

When did the FCAT come into being?

FCAT was a statutory body constituted set up by the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting in 1983, under Section 5D of the Cinematograph Act, 1952. Its main job was to hear appeals filed under Section 5C of the Cinematograph Act, by applicants for certification aggrieved by the decision of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). The tribunal was headed by a chairperson and had four other members, including a Secretary appointed by the Government of India to handle. The Tribunal was headquartered in New Delhi. Before the FCAT, filmmakers had no option but to approach the court to seek redressal against CBFC certifications or suggested cuts. So, the FCAT acted like a buffer for filmmakers, and decisions taken by the tribunal were quick, though not always beyond reproach.

How important was the FCAT in the certification process?

In India, all films must have a CBFC certificate if they are to be released theatrically, telecast on television, or displayed publicly in any way. The CBFC — which consists of a Chairperson and 23 members, all appointed by the Government of India — certifies films under four categories:

U: Unrestricted public exhibition (Suitable for all age groups)

U/A: Parental guidance for children under age 12

A: Restricted to adults (Suitable for 18 years and above

S: Restricted to a specialised group of people, such as engineers, doctors or scientists.

The CBFC can also deny certification a film. On several occasions when a filmmaker or producer has not been satisfied with the CBFC’s certification, or with a denial, they have appealed to the FCAT. And in many cases, the FCAT has overturned the CBFC decision.

According to observers, the CBFC was increasingly getting stacked with people close to the ruling dispensation, both the Congress and the BJP. Of late, the body has been headed by chairpersons who have ruled with a heavy hand and ordered cuts to films critical of the government. The clash between the film fraternity and the certification body became more pronounced in 2015 with the appointment of Pahlaj Nihalani as the chairman of the CBFC, and the FCAT had to step in often to sort out disputes. “In the context of a ban on a film or an order to delete scenes and dialogues from a film, the FCAT was called upon to frame the objections of the certification board in the context of the constitutional framework of freedom of expression,” said Lalit Bhasin, former chairperson of the FCAT. Some recent films like Shaheb Bibi Golaam and Lipstick Under My Burkha, both released in 2016, got a favourable hearing from the FCAT. The documentary, En Dino Muzaffarnagar, made by filmmakers Shubhradeep Chakravorty and Meera Chaudhary, was denied certification.

Mr. Bhasin, who was also part of the Justice Mukul Mudgal Committee, which examined the certification process and suggested recommendations, said, “Neither the Mudgal committee nor the Shyam Benegal committee recommended that the FCAT be scrapped.” Among other objectives, the rationale for setting up the FCAT was to reduce the burden on courts by functioning as an appellate body. Mr. Bhasin added that the tribunal, under him, took swift decisions, usually in six weeks.

Why has the tribunal been abolished?

The move to abolish the FCAT along with other tribunals follows a Supreme Court order in Madras Bar Association vs. Union of India. In November last year, a two-member Bench directed the government to constitute a National Tribunals Commission. It said the Commission would “act as an independent body to supervise the appointments and functioning of Tribunals, as well as to conduct disciplinary proceedings against members of Tribunals and to take care of administrative and infrastructural needs of the Tribunals, in an appropriate manner”. The top court, addressing the issue of dependence of tribunals on the executive for administrative requirements, recommended the creation of an umbrella organisation that would be an independent supervisory body to oversee the working of tribunals.

“The court had expressed that the functioning of tribunals could be strengthened. So, the government cannot take advantage of the order and take shelter under it,” said Mr. Bhasin. The move to abolish the FCAT is surprising as it comes in the backdrop of the recommendations of two influential panels — the Mudgal Committee and the Benegal Committee — both of which suggested an expansion of the body’s jurisdiction.

What happens now?

Now that the FCAT has been disbanded, it will be left to the already overburdened courts to adjudicate. With the government tightening its control on over-the-top (OTT) content and ordering players in this area to set up a grievance redressal body to address the concerns of the viewers, many observers point out that the courts will have to play a greater role as an avenue of appeal. With cases pending for years, it is anybody’s guess how long the same courts will take to adjudicate on matters of film certification. The role played by the FCAT, which used to handle at least 20 cases a month, will now have to be performed by courts. That includes watching and reviewing films in their entirety to understand the process of certification.

Key decisions

Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016): It had been denied certification in 2017, on the ground that it was “lady-oriented”. Pahlaj Nihalani was CBFC Chairperson at the time. Director Alankrita Shrivastava appealed to the FCAT, following whose ruling some scenes were cut and the film was released, with an ‘A’ certificate.

MSG: The Messenger of God (2015): The film features the controversial Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insan of Dera Saccha Sauda. The CBFC, then chaired by Leela Samson, had denied it a certificate. The FCAT cleared the film for release; Samson resigned in protest.

Haraamkhor (2015): Starring Nawazuddin Siddique, the film revolves around the relationship between a schoolteacher and a young female student. It had been denied certification by the CBFC for being “very provocative”. The FCAT cleared the film and said it was “furthering a social message and warning the girls to be aware of their rights”.

Kaalakandi (2018): The CBFC suggested 72 cuts to the film, which features Saif Ali Khan. The filmmakers appealed to the FCAT, following which the film got a U/A rating, with only one cut.

When did the FCAT come into being?

FCAT was a statutory body constituted set up by the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting in 1983, under Section 5D of the Cinematograph Act, 1952. Its main job was to hear appeals filed under Section 5C of the Cinematograph Act, by applicants for certification aggrieved by the decision of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). The tribunal was headed by a chairperson and had four other members, including a Secretary appointed by the Government of India to handle. The Tribunal was headquartered in New Delhi. Before the FCAT, filmmakers had no option but to approach the court to seek redressal against CBFC certifications or suggested cuts. So, the FCAT acted like a buffer for filmmakers, and decisions taken by the tribunal were quick, though not always beyond reproach.

How important was the FCAT in the certification process?

In India, all films must have a CBFC certificate if they are to be released theatrically, telecast on television, or displayed publicly in any way. The CBFC — which consists of a Chairperson and 23 members, all appointed by the Government of India — certifies films under four categories:

U: Unrestricted public exhibition (Suitable for all age groups)

U/A: Parental guidance for children under age 12

A: Restricted to adults (Suitable for 18 years and above

S: Restricted to a specialised group of people, such as engineers, doctors or scientists.

The CBFC can also deny certification a film. On several occasions when a filmmaker or producer has not been satisfied with the CBFC’s certification, or with a denial, they have appealed to the FCAT. And in many cases, the FCAT has overturned the CBFC decision.

According to observers, the CBFC was increasingly getting stacked with people close to the ruling dispensation, both the Congress and the BJP. Of late, the body has been headed by chairpersons who have ruled with a heavy hand and ordered cuts to films critical of the government. The clash between the film fraternity and the certification body became more pronounced in 2015 with the appointment of Pahlaj Nihalani as the chairman of the CBFC, and the FCAT had to step in often to sort out disputes. “In the context of a ban on a film or an order to delete scenes and dialogues from a film, the FCAT was called upon to frame the objections of the certification board in the context of the constitutional framework of freedom of expression,” said Lalit Bhasin, former chairperson of the FCAT. Some recent films like Shaheb Bibi Golaam and Lipstick Under My Burkha, both released in 2016, got a favourable hearing from the FCAT. The documentary, En Dino Muzaffarnagar, made by filmmakers Shubhradeep Chakravorty and Meera Chaudhary, was denied certification.

Mr. Bhasin, who was also part of the Justice Mukul Mudgal Committee, which examined the certification process and suggested recommendations, said, “Neither the Mudgal committee nor the Shyam Benegal committee recommended that the FCAT be scrapped.” Among other objectives, the rationale for setting up the FCAT was to reduce the burden on courts by functioning as an appellate body. Mr. Bhasin added that the tribunal, under him, took swift decisions, usually in six weeks.

Why has the tribunal been abolished?

The move to abolish the FCAT along with other tribunals follows a Supreme Court order in Madras Bar Association vs. Union of India. In November last year, a two-member Bench directed the government to constitute a National Tribunals Commission. It said the Commission would “act as an independent body to supervise the appointments and functioning of Tribunals, as well as to conduct disciplinary proceedings against members of Tribunals and to take care of administrative and infrastructural needs of the Tribunals, in an appropriate manner”. The top court, addressing the issue of dependence of tribunals on the executive for administrative requirements, recommended the creation of an umbrella organisation that would be an independent supervisory body to oversee the working of tribunals.

“The court had expressed that the functioning of tribunals could be strengthened. So, the government cannot take advantage of the order and take shelter under it,” said Mr. Bhasin. The move to abolish the FCAT is surprising as it comes in the backdrop of the recommendations of two influential panels — the Mudgal Committee and the Benegal Committee — both of which suggested an expansion of the body’s jurisdiction.

What happens now?

Now that the FCAT has been disbanded, it will be left to the already overburdened courts to adjudicate. With the government tightening its control on over-the-top (OTT) content and ordering players in this area to set up a grievance redressal body to address the concerns of the viewers, many observers point out that the courts will have to play a greater role as an avenue of appeal. With cases pending for years, it is anybody’s guess how long the same courts will take to adjudicate on matters of film certification. The role played by the FCAT, which used to handle at least 20 cases a month, will now have to be performed by courts. That includes watching and reviewing films in their entirety to understand the process of certification.

Key decisions

Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016): It had been denied certification in 2017, on the ground that it was “lady-oriented”. Pahlaj Nihalani was CBFC Chairperson at the time. Director Alankrita Shrivastava appealed to the FCAT, following whose ruling some scenes were cut and the film was released, with an ‘A’ certificate.

MSG: The Messenger of God (2015): The film features the controversial Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insan of Dera Saccha Sauda. The CBFC, then chaired by Leela Samson, had denied it a certificate. The FCAT cleared the film for release; Samson resigned in protest.

Haraamkhor (2015): Starring Nawazuddin Siddique, the film revolves around the relationship between a schoolteacher and a young female student. It had been denied certification by the CBFC for being “very provocative”. The FCAT cleared the film and said it was “furthering a social message and warning the girls to be aware of their rights”.

Kaalakandi (2018): The CBFC suggested 72 cuts to the film, which features Saif Ali Khan. The filmmakers appealed to the FCAT, following which the film got a U/A rating, with only one cut.

What next

The abolition means filmmakers will now have to approach the High Court whenever they want to challenge a CBFC certification, or lack of it.

The sudden move has upset many filmmakers. “Such a sad day for cinema,” filmmaker Vishal Bharadwaj tweeted, posting a news link on the abolition.

Director Hansal Mehta tweeted: “Do the high courts have a lot of time to address film certification grievances? How many film producers will have the means to approach the courts? The FCAT discontinuation feels arbitrary and is definitely restrictive. Why this unfortunate timing? Why take this decision at all?”.

What next

The abolition means filmmakers will now have to approach the High Court whenever they want to challenge a CBFC certification, or lack of it.

The sudden move has upset many filmmakers. “Such a sad day for cinema,” filmmaker Vishal Bharadwaj tweeted, posting a news link on the abolition.

Director Hansal Mehta tweeted: “Do the high courts have a lot of time to address film certification grievances? How many film producers will have the means to approach the courts? The FCAT discontinuation feels arbitrary and is definitely restrictive. Why this unfortunate timing? Why take this decision at all?”.

Latest News

Latest News General Studies

General Studies