- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

The Tribunal Reforms Bill 2021 and why it has put Modi govt in Supreme Court’s crosshairs?.

The Supreme Court recently expressed its discontentment over the functioning of tribunals in the country, given that several of these important quasi-judicial bodies are understaffed. In a hearing on 6 August 2021, a Bench led by Chief Justice of India N V Ramana asked the government if it intends to shut down tribunals that have several key vacant posts. This came days after Lok Sabha passed a Bill to dissolve at least eight tribunals.

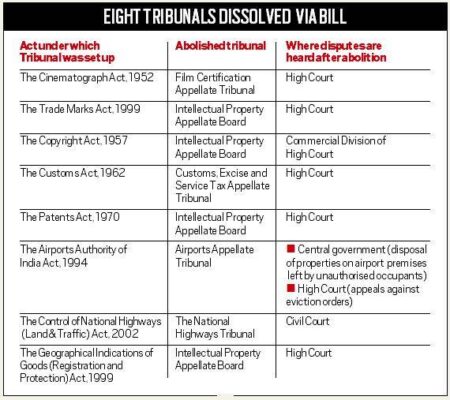

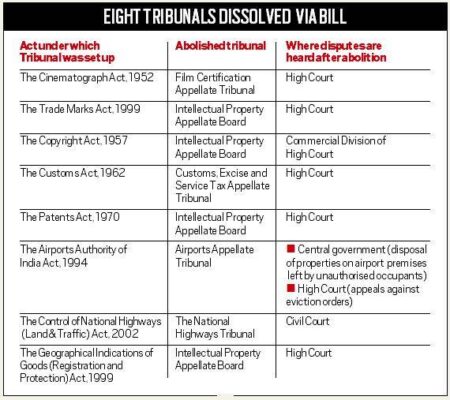

The Tribunals Reforms Bill, 2021 replaces a similar Ordinance promulgated in April 2021 that sought to dissolve eight tribunals that functioned as appellate bodies to hear disputes under various statutes, and transferred their functions to existing judicial forums such as a civil court or a High Court.

The Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and was passed on 3 August 2021 amid protests by the Opposition over the Pegasus issue.

The Bill states that the Chairpersons and Members of the tribunal being abolished shall cease to hold office, and they will be entitled to claim compensation equivalent to three months’ pay and allowances for their premature termination. It also proposes changes in the process of appointment of certain other tribunals.

While the Bill provides for uniform pay and rules for the search and selection committees across tribunals, it also provides for removal of tribunal members. It states that the central government shall, on the recommendation of the Search-cum-Selection Committee, remove from office any Chairperson or a Member, who—

(a) has been adjudged as an insolvent; or

(b) has been convicted of an offence which involves moral turpitude; or

(c) has become physically or mentally incapable of acting as such Chairperson or Member; or

(d) has acquired such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions as such Chairperson or Member; or

(e) has so abused his position as to render his continuance in office prejudicial to the public interest.

Chairpersons and judicial members of tribunals are former judges of High Courts and the Supreme Court. While the move brings greater accountability on the functioning of the tribunals, it also raises questions on the independence of these judicial bodies.

In the Search-cum-Selection Committee for state tribunals, the Bill brings in the Chief Secretary of the state and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state who will have a vote and Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s General Administrative Department with no voting right. This gives the government a foot in the door in the process. The Chief Justice of the High Court, who would head the committee, will not have a casting vote.

What are the tribunals that are being dissolved?

Among the key ones are the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) under the Cinematograph Act, 1952; the Intellectual Property Appellate Board under the Copyrights Act, 1957; and the Customs Excise and Service Tax Appealate Tribunal.

The government has said that analysis of data of the last three years has shown that tribunals in several sectors have not necessarily led to faster justice delivery and they are also at a considerable expense to the exchequer. This has led to the decision to rationalise the functioning of tribunals, a process that it began in 2015.

India now has 16 tribunals including the National Green Tribunal, the Armed Forces Appellate Tribunal, the Debt Recovery Tribunal among others which also suffer from crippling vacancies as the SC has noted.

What happens to cases pending before the tribunals dissolved?

These cases will be transferred to High Courts or commercial civil courts immediately. Legal experts have been divided on the efficacy of the government’s move. While on the one hand, the cases might get a faster hearing and disposal if taken to High Courts, experts fear that the lack of specialisation in regular courts could be detrimental to the decision-making process. For example, the FCAT exclusively heard decisions appealing against decisions of the censor board, which requires expertise in art and cinema.

The Bill states that the Chairpersons and Members of the tribunal being abolished shall cease to hold office, and they will be entitled to claim compensation equivalent to three months’ pay and allowances for their premature termination. It also proposes changes in the process of appointment of certain other tribunals.

While the Bill provides for uniform pay and rules for the search and selection committees across tribunals, it also provides for removal of tribunal members. It states that the central government shall, on the recommendation of the Search-cum-Selection Committee, remove from office any Chairperson or a Member, who—

(a) has been adjudged as an insolvent; or

(b) has been convicted of an offence which involves moral turpitude; or

(c) has become physically or mentally incapable of acting as such Chairperson or Member; or

(d) has acquired such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions as such Chairperson or Member; or

(e) has so abused his position as to render his continuance in office prejudicial to the public interest.

Chairpersons and judicial members of tribunals are former judges of High Courts and the Supreme Court. While the move brings greater accountability on the functioning of the tribunals, it also raises questions on the independence of these judicial bodies.

In the Search-cum-Selection Committee for state tribunals, the Bill brings in the Chief Secretary of the state and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state who will have a vote and Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s General Administrative Department with no voting right. This gives the government a foot in the door in the process. The Chief Justice of the High Court, who would head the committee, will not have a casting vote.

What are the tribunals that are being dissolved?

Among the key ones are the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) under the Cinematograph Act, 1952; the Intellectual Property Appellate Board under the Copyrights Act, 1957; and the Customs Excise and Service Tax Appealate Tribunal.

The government has said that analysis of data of the last three years has shown that tribunals in several sectors have not necessarily led to faster justice delivery and they are also at a considerable expense to the exchequer. This has led to the decision to rationalise the functioning of tribunals, a process that it began in 2015.

India now has 16 tribunals including the National Green Tribunal, the Armed Forces Appellate Tribunal, the Debt Recovery Tribunal among others which also suffer from crippling vacancies as the SC has noted.

What happens to cases pending before the tribunals dissolved?

These cases will be transferred to High Courts or commercial civil courts immediately. Legal experts have been divided on the efficacy of the government’s move. While on the one hand, the cases might get a faster hearing and disposal if taken to High Courts, experts fear that the lack of specialisation in regular courts could be detrimental to the decision-making process. For example, the FCAT exclusively heard decisions appealing against decisions of the censor board, which requires expertise in art and cinema.

The Bill states that the Chairpersons and Members of the tribunal being abolished shall cease to hold office, and they will be entitled to claim compensation equivalent to three months’ pay and allowances for their premature termination. It also proposes changes in the process of appointment of certain other tribunals.

While the Bill provides for uniform pay and rules for the search and selection committees across tribunals, it also provides for removal of tribunal members. It states that the central government shall, on the recommendation of the Search-cum-Selection Committee, remove from office any Chairperson or a Member, who—

(a) has been adjudged as an insolvent; or

(b) has been convicted of an offence which involves moral turpitude; or

(c) has become physically or mentally incapable of acting as such Chairperson or Member; or

(d) has acquired such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions as such Chairperson or Member; or

(e) has so abused his position as to render his continuance in office prejudicial to the public interest.

Chairpersons and judicial members of tribunals are former judges of High Courts and the Supreme Court. While the move brings greater accountability on the functioning of the tribunals, it also raises questions on the independence of these judicial bodies.

In the Search-cum-Selection Committee for state tribunals, the Bill brings in the Chief Secretary of the state and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state who will have a vote and Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s General Administrative Department with no voting right. This gives the government a foot in the door in the process. The Chief Justice of the High Court, who would head the committee, will not have a casting vote.

What are the tribunals that are being dissolved?

Among the key ones are the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) under the Cinematograph Act, 1952; the Intellectual Property Appellate Board under the Copyrights Act, 1957; and the Customs Excise and Service Tax Appealate Tribunal.

The government has said that analysis of data of the last three years has shown that tribunals in several sectors have not necessarily led to faster justice delivery and they are also at a considerable expense to the exchequer. This has led to the decision to rationalise the functioning of tribunals, a process that it began in 2015.

India now has 16 tribunals including the National Green Tribunal, the Armed Forces Appellate Tribunal, the Debt Recovery Tribunal among others which also suffer from crippling vacancies as the SC has noted.

What happens to cases pending before the tribunals dissolved?

These cases will be transferred to High Courts or commercial civil courts immediately. Legal experts have been divided on the efficacy of the government’s move. While on the one hand, the cases might get a faster hearing and disposal if taken to High Courts, experts fear that the lack of specialisation in regular courts could be detrimental to the decision-making process. For example, the FCAT exclusively heard decisions appealing against decisions of the censor board, which requires expertise in art and cinema.

The Bill states that the Chairpersons and Members of the tribunal being abolished shall cease to hold office, and they will be entitled to claim compensation equivalent to three months’ pay and allowances for their premature termination. It also proposes changes in the process of appointment of certain other tribunals.

While the Bill provides for uniform pay and rules for the search and selection committees across tribunals, it also provides for removal of tribunal members. It states that the central government shall, on the recommendation of the Search-cum-Selection Committee, remove from office any Chairperson or a Member, who—

(a) has been adjudged as an insolvent; or

(b) has been convicted of an offence which involves moral turpitude; or

(c) has become physically or mentally incapable of acting as such Chairperson or Member; or

(d) has acquired such financial or other interest as is likely to affect prejudicially his functions as such Chairperson or Member; or

(e) has so abused his position as to render his continuance in office prejudicial to the public interest.

Chairpersons and judicial members of tribunals are former judges of High Courts and the Supreme Court. While the move brings greater accountability on the functioning of the tribunals, it also raises questions on the independence of these judicial bodies.

In the Search-cum-Selection Committee for state tribunals, the Bill brings in the Chief Secretary of the state and the Chairman of the Public Service Commission of the concerned state who will have a vote and Secretary or Principal Secretary of the state’s General Administrative Department with no voting right. This gives the government a foot in the door in the process. The Chief Justice of the High Court, who would head the committee, will not have a casting vote.

What are the tribunals that are being dissolved?

Among the key ones are the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) under the Cinematograph Act, 1952; the Intellectual Property Appellate Board under the Copyrights Act, 1957; and the Customs Excise and Service Tax Appealate Tribunal.

The government has said that analysis of data of the last three years has shown that tribunals in several sectors have not necessarily led to faster justice delivery and they are also at a considerable expense to the exchequer. This has led to the decision to rationalise the functioning of tribunals, a process that it began in 2015.

India now has 16 tribunals including the National Green Tribunal, the Armed Forces Appellate Tribunal, the Debt Recovery Tribunal among others which also suffer from crippling vacancies as the SC has noted.

What happens to cases pending before the tribunals dissolved?

These cases will be transferred to High Courts or commercial civil courts immediately. Legal experts have been divided on the efficacy of the government’s move. While on the one hand, the cases might get a faster hearing and disposal if taken to High Courts, experts fear that the lack of specialisation in regular courts could be detrimental to the decision-making process. For example, the FCAT exclusively heard decisions appealing against decisions of the censor board, which requires expertise in art and cinema.

Latest News

Latest News General Studies

General Studies