EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

The absurdity and efficacy of the anti-defection law

Jignesh Mewani, an independent MLA from Gujarat, has said he has joined the Congress “in spirit” as he could not formally do so, having been elected as an independent.

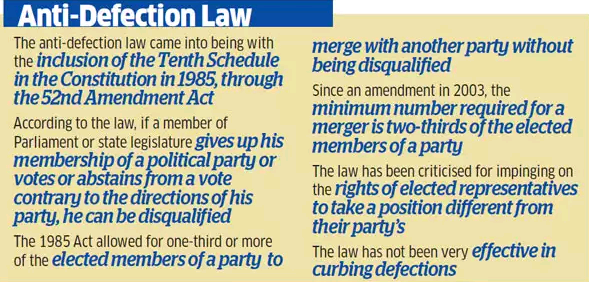

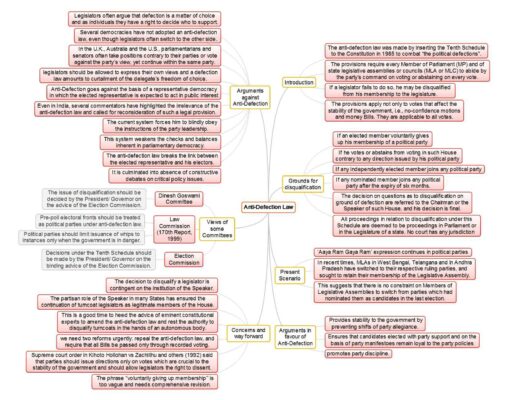

The Tenth Schedule of the Constitution, popularly known as the anti-defection law, specifies the circumstances under which changing of political parties by legislators’ invites action under the law. It includes situations in which an independent MLA, too, joins a party after the election.

The 3 scenarios

The law covers three scenarios with respect to shifting of political parties by an MP or an MLA. The first is when a member elected on the ticket of a political party “voluntarily gives up” membership of such a party or votes in the House against the wishes of the party. The second is when a legislator who has won his or her seat as an independent candidate joins a political party after the election.

In both these instances, the legislator loses the seat in the legislature on changing (or joining) a party.

The third scenario relates to nominated MPs. In their case, the law gives them six months to join a political party, after being nominated. If they join a party after such time, they stand to lose their seat in the House.

Covering independents

In 1969, a committee chaired by Home Minister Y B Chavan examined the issue of defection. It observed that after the 1967 general elections, defections changed the political scene in India: 176 of 376 independent legislators later joined a political party. However, the committee did not recommend any action against independent legislators. A member disagreed with the committee on the issue of independents and wanted them disqualified if they joined a political party.

In the absence of a recommendation on this issue by the Chavan committee, the initial attempts at creating the anti-defection law (1969, 1973) did not cover independent legislators joining political parties. The next legislative attempt, in 1978, allowed independent and nominated legislators to join a political party once. But when the Constitution was amended in 1985, independent legislators were prevented from joining a political party and nominated legislators were given six months’ time.

Disqualification

Under the anti-defection law, the power to decide the disqualification of an MP or MLA rests with the presiding officerof the legislature. The law does not specify a time frame in which such a decision has to be made.

As a result, Speakers of legislatures have sometimes acted very quickly or have delayed the decision for years — and have been accused of political bias in both situations. Last year, the Supreme Court observed that anti-defection cases should be decided by Speakers in three months’ time.

In West Bengal, a disqualification petition against Mukul Roy, BJP MLA now back in the Trinamool Congress, has been pending with the Assembly Speaker since June 17. The Calcutta High Court referred to the Supreme Court order, observed that the three-month window has now passed, and directed the Speaker to decide on the petition against Roy by October 7.

Jignesh Mewani, an independent MLA from Gujarat, has said he has joined the Congress “in spirit” as he could not formally do so, having been elected as an independent.

The Tenth Schedule of the Constitution, popularly known as the anti-defection law, specifies the circumstances under which changing of political parties by legislators’ invites action under the law. It includes situations in which an independent MLA, too, joins a party after the election.

The 3 scenarios

The law covers three scenarios with respect to shifting of political parties by an MP or an MLA. The first is when a member elected on the ticket of a political party “voluntarily gives up” membership of such a party or votes in the House against the wishes of the party. The second is when a legislator who has won his or her seat as an independent candidate joins a political party after the election.

In both these instances, the legislator loses the seat in the legislature on changing (or joining) a party.

The third scenario relates to nominated MPs. In their case, the law gives them six months to join a political party, after being nominated. If they join a party after such time, they stand to lose their seat in the House.

Covering independents

In 1969, a committee chaired by Home Minister Y B Chavan examined the issue of defection. It observed that after the 1967 general elections, defections changed the political scene in India: 176 of 376 independent legislators later joined a political party. However, the committee did not recommend any action against independent legislators. A member disagreed with the committee on the issue of independents and wanted them disqualified if they joined a political party.

In the absence of a recommendation on this issue by the Chavan committee, the initial attempts at creating the anti-defection law (1969, 1973) did not cover independent legislators joining political parties. The next legislative attempt, in 1978, allowed independent and nominated legislators to join a political party once. But when the Constitution was amended in 1985, independent legislators were prevented from joining a political party and nominated legislators were given six months’ time.

Disqualification

Under the anti-defection law, the power to decide the disqualification of an MP or MLA rests with the presiding officerof the legislature. The law does not specify a time frame in which such a decision has to be made.

As a result, Speakers of legislatures have sometimes acted very quickly or have delayed the decision for years — and have been accused of political bias in both situations. Last year, the Supreme Court observed that anti-defection cases should be decided by Speakers in three months’ time.

In West Bengal, a disqualification petition against Mukul Roy, BJP MLA now back in the Trinamool Congress, has been pending with the Assembly Speaker since June 17. The Calcutta High Court referred to the Supreme Court order, observed that the three-month window has now passed, and directed the Speaker to decide on the petition against Roy by October 7.

Next

previous

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

Jignesh Mewani, an independent MLA from Gujarat, has said he has joined the Congress “in spirit” as he could not formally do so, having been elected as an independent.

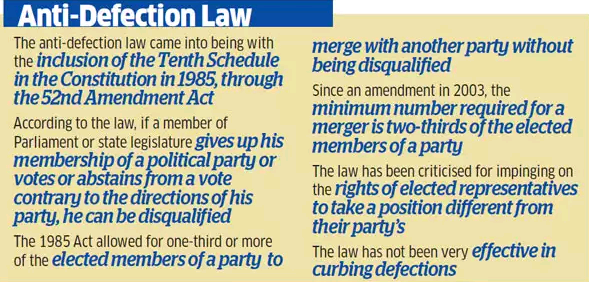

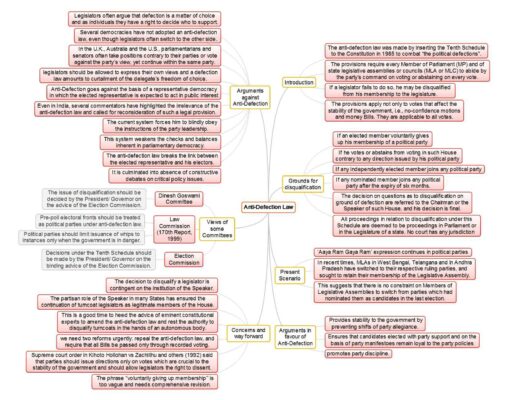

The Tenth Schedule of the Constitution, popularly known as the anti-defection law, specifies the circumstances under which changing of political parties by legislators’ invites action under the law. It includes situations in which an independent MLA, too, joins a party after the election.

The 3 scenarios

The law covers three scenarios with respect to shifting of political parties by an MP or an MLA. The first is when a member elected on the ticket of a political party “voluntarily gives up” membership of such a party or votes in the House against the wishes of the party. The second is when a legislator who has won his or her seat as an independent candidate joins a political party after the election.

In both these instances, the legislator loses the seat in the legislature on changing (or joining) a party.

The third scenario relates to nominated MPs. In their case, the law gives them six months to join a political party, after being nominated. If they join a party after such time, they stand to lose their seat in the House.

Covering independents

In 1969, a committee chaired by Home Minister Y B Chavan examined the issue of defection. It observed that after the 1967 general elections, defections changed the political scene in India: 176 of 376 independent legislators later joined a political party. However, the committee did not recommend any action against independent legislators. A member disagreed with the committee on the issue of independents and wanted them disqualified if they joined a political party.

In the absence of a recommendation on this issue by the Chavan committee, the initial attempts at creating the anti-defection law (1969, 1973) did not cover independent legislators joining political parties. The next legislative attempt, in 1978, allowed independent and nominated legislators to join a political party once. But when the Constitution was amended in 1985, independent legislators were prevented from joining a political party and nominated legislators were given six months’ time.

Disqualification

Under the anti-defection law, the power to decide the disqualification of an MP or MLA rests with the presiding officerof the legislature. The law does not specify a time frame in which such a decision has to be made.

As a result, Speakers of legislatures have sometimes acted very quickly or have delayed the decision for years — and have been accused of political bias in both situations. Last year, the Supreme Court observed that anti-defection cases should be decided by Speakers in three months’ time.

In West Bengal, a disqualification petition against Mukul Roy, BJP MLA now back in the Trinamool Congress, has been pending with the Assembly Speaker since June 17. The Calcutta High Court referred to the Supreme Court order, observed that the three-month window has now passed, and directed the Speaker to decide on the petition against Roy by October 7.

Jignesh Mewani, an independent MLA from Gujarat, has said he has joined the Congress “in spirit” as he could not formally do so, having been elected as an independent.

The Tenth Schedule of the Constitution, popularly known as the anti-defection law, specifies the circumstances under which changing of political parties by legislators’ invites action under the law. It includes situations in which an independent MLA, too, joins a party after the election.

The 3 scenarios

The law covers three scenarios with respect to shifting of political parties by an MP or an MLA. The first is when a member elected on the ticket of a political party “voluntarily gives up” membership of such a party or votes in the House against the wishes of the party. The second is when a legislator who has won his or her seat as an independent candidate joins a political party after the election.

In both these instances, the legislator loses the seat in the legislature on changing (or joining) a party.

The third scenario relates to nominated MPs. In their case, the law gives them six months to join a political party, after being nominated. If they join a party after such time, they stand to lose their seat in the House.

Covering independents

In 1969, a committee chaired by Home Minister Y B Chavan examined the issue of defection. It observed that after the 1967 general elections, defections changed the political scene in India: 176 of 376 independent legislators later joined a political party. However, the committee did not recommend any action against independent legislators. A member disagreed with the committee on the issue of independents and wanted them disqualified if they joined a political party.

In the absence of a recommendation on this issue by the Chavan committee, the initial attempts at creating the anti-defection law (1969, 1973) did not cover independent legislators joining political parties. The next legislative attempt, in 1978, allowed independent and nominated legislators to join a political party once. But when the Constitution was amended in 1985, independent legislators were prevented from joining a political party and nominated legislators were given six months’ time.

Disqualification

Under the anti-defection law, the power to decide the disqualification of an MP or MLA rests with the presiding officerof the legislature. The law does not specify a time frame in which such a decision has to be made.

As a result, Speakers of legislatures have sometimes acted very quickly or have delayed the decision for years — and have been accused of political bias in both situations. Last year, the Supreme Court observed that anti-defection cases should be decided by Speakers in three months’ time.

In West Bengal, a disqualification petition against Mukul Roy, BJP MLA now back in the Trinamool Congress, has been pending with the Assembly Speaker since June 17. The Calcutta High Court referred to the Supreme Court order, observed that the three-month window has now passed, and directed the Speaker to decide on the petition against Roy by October 7.

Latest News

Latest News General Studies

General Studies