- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

The GM mustard debate

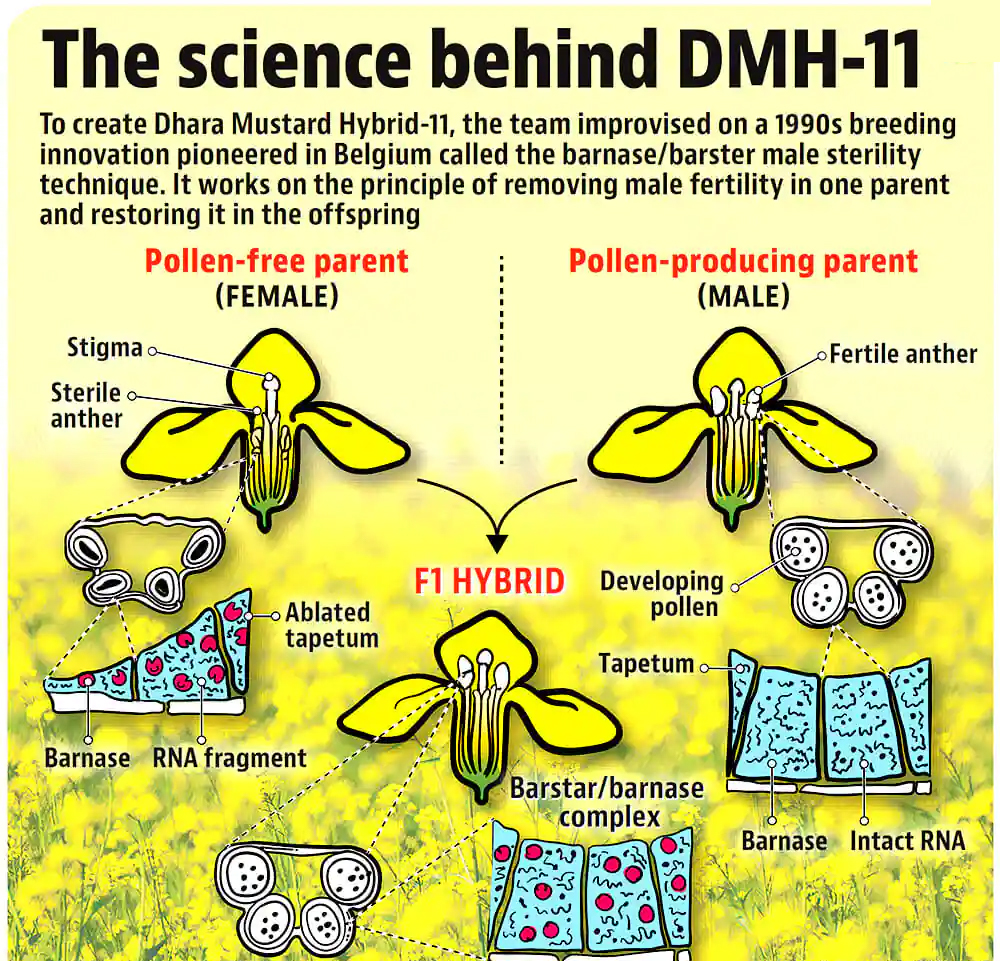

- The debate over the use of genetically modified cropsis raging again, with familiar arguments and objections being made. Recently, the government had cleared the ‘environmental release’ of a genetically modified (GM) variety of mustard, DMH-11, developed by the Centre for Genetic Manipulation of Crop Plants (CGMCP) at Delhi University. ‘Environmental release’, involving seed production and field testing, is the final step before the crop can be cultivated by farmers.

- The government decision was met with expected opposition from activists who oppose any use of GM technology in agriculture. Predictably, the matter has reached the courts. On previous occasions, this has ended with the decision being put on indefinite hold.

- Previous attempt

- In fact, DMH-11had reached quite close to being approved for environmental release in 2017 as well, but then had to be stopped under pressure from activists and NGOs. The decision to revisit this issue has come in the wake of steadily rising import bills on edible oils. The availability of mustard, commonly used affordable cooking oil, has emerged, more than ever before, as a food security issue. Increased yields of mustard can reduce the dependence on other countries for a critical food item, as well as save foreign currency worth tens of billions of dollars every year.

- In fact, the government is treating mustard as a special case among all the GM crops awaiting approval. It has maintained that approving the mustard variety would not mean opening the floodgates for all other transgenic crops. In the case of mustard, there is a compelling economic and food security argument, which puts it in a separate category. There has been no movement, for example, on Bt brinjal, which, like DMH-11, has passed all the safety tests and regulatory processes, but whose release has been on hold since 2010.

- Activists, however, not just dispute the ability of GM mustard to increase yield, but question biosafety dataand claim that it will harm human and soil health, cause environmental damage, and threaten the existence of other species, like honeybees. These arguments are in line with the opposition to genetically modified crops in general.

Concerns around the crop

- The opposition to GM cropsbroadly rests on the ‘precautionary principle’, which argues that in the absence of scientific consensus and adequate information, new innovations likely to have severe adverse impacts on human or environmental health must be treated with extreme caution.

- The principle is criticised, even though it is invoked fairly regularly in a variety of circumstances. The sole reliance on this principle for decision-makingis often seen as a hurdle to scientific progress, or a justification for inaction. GM crops have been under cultivation for three decades now, in different parts of the world, and there is little evidence to suggest that the apocalyptic dangers that are often talked about have appeared anywhere.

- Over 25 countries grow geneticially modified crops, including developed nationslike the United States and Canada, middle income countries like Brazil and South Africa, and India’s neighbours like Pakistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh. Even in India, Bt cotton, the only GM crop to have been allowed in the country, has been under cultivation for the last 20 years. None of the grave apprehensions that were raised when Bt cotton was being approved have come true.

- In fact, a substantial portion of imported edible oils, as well as some other crops, are of genetically modified varieties. Many Indians have, thus, already consumed genetically modified food without any harm.

- It is true that a scientific consensus on the use of GM technology in agricultureis still elusive. But it is difficult to have complete consensus on any emerging area of science. After three decades of use, the weight of scientific opinion seems overwhelmingly in favour of GM technology. In fact, while endorsing DMH-11, the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the main academic association of agricultural scientists, had said that most of the opposition to GM crops was based on distortions of scientific data.

- “The broad conclusion is that almost all the negative reports on GM mustard, appearing on websites, newspapers, and letters to the ministers and PMO are fallacious, wilfully distort scientific dataand have been made with the sole intention of scuttling the use of technology which could be of great interest and value to the country,” the NAAS had said in 2017 after DMH-11 was put on hold.

- Scientists also lament the factthat the uncertainties inherent in any new technology are exaggerated to either call for a complete ban on GM, or fresh round of safety tests.

- “There is a constant shifting of goalposts. A certain requirement is asked to be met, and when that is done, new demands are put forward. This is an endless cycle. The fact is that GM mustard, and GM technology in general, has been put through the most robust scientific scrutiny possible. It is being used in several countries, including India where GM cotton is being cultivated for two decades now,” Vibha Dhawan, director general of Delhi-based The Energy and Resources Institute, and herself an agriculture biotechnologist, said.

- “We see very absolutist positionsbeing taken on GM technology by those who oppose it. Every small potential risk is cited to argue against its use. We have to understand that nothing is risk-free. All the available scientific evidence suggests that genetically modified crops are safe for human consumption. But we hear arguments that the harmful impacts can manifest in the second, or fourth or fifth generation of consumers. There can be no answer to this,” she said.

- The opposition to GM cropsso far has overcome the broad political agreement on the subject. Both the Congress as well as BJP at the Centre have tried to push for these crops. On the state level, there is less consensus, with many state governments expressing reservations over this technology.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies