Right to be Forgotten: Privacy vs Freedom

Ashutosh Kaushik who won reality shows Bigg Boss in 2008 and MTV Roadies 5.0 has approached the Delhi High Court with a plea saying that his videos, photographs and articles etc. be removed from the internet citing his “Right to be Forgotten”.

In the plea, Kaushik also maintains that the “Right to be Forgotten” goes in sync with the “Right to Privacy”, which is an integral part of Article 21 of the Constitution, which concerns the right to life.

Kaushik’s plea mentions that the posts and videos on internet related to him have caused the “petitioner psychological pain for his diminutive acts, which were erroneously committed a decade ago as the recorded videos, photos, articles of the same are available on various search engines/ online platforms”.

The plea also states that “the petitioner’s mistakes in his personal life becomes and remains in public knowledge for generations to come and therefore in the instant case, this aspect acts as an ingredient for litigation before this Hon’ble court. Consequently, the values enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and the emergent jurisprudential concept of the Right to be Forgotten becomes extremely relevant in the present case.”

Kaushik’s plea refers to an incident from 2009 when he was held by the Mumbai traffic police for drunken driving. About ten days after Kaushik’s arrest, the metropolitan magistrate court sentenced him to one-day imprisonment, imposed a fine of Rs 3,100 and also suspended his driving licence for two years. At the time, Kaushik was charged for drunken driving, for not wearing a helmet, for not carrying his driving licence and for not obeying the police officers who were on duty.

The matter was heard by the single Judge bench of Justice Rekha Palli. The next hearing on this matter will be held on 20 August 2021.

The Right to be Forgotten falls under the purview of an individual’s right to privacy, which is governed by the Personal Data Protection Bill that is yet to be passed by Parliament.

In 2017, the Right to Privacy was declared a fundamental right by the Supreme Court in its landmark verdict. The court said at the time that, “the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 and as a part of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution”.

The Personal Data Protection Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha on 11 December 2019 and it aims to set out provisions meant for the protection of the personal data of individuals.

Clause 20 under Chapter V of this draft bill titled “Rights of Data Principal” mentions the “Right to be Forgotten.” It states that the “data principal (the person to whom the data is related) shall have the right to restrict or prevent the continuing disclosure of his personal data by a data fiduciary”.

Therefore, broadly, under the Right to be forgotten, users can de-link, limit, delete or correct the disclosure of their personal information held by data fiduciaries. A data fiduciary means any person, including the State, a company, any juristic entity or any individual who alone or in conjunction with others determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data.

Even so, the sensitivity of the personal data and information cannot be determined independently by the person concerned, but will be overseen by the Data Protection Authority (DPA). This means that while the draft bill gives some provisions under which a data principal can seek that his data be removed, but his or her rights are subject to authorisation by the Adjudicating Officer who works for the DPA.

While assessing the data principal’s request, this officer will need to examine the sensitivity of the personal data, the scale of disclosure, degree of accessibility sought to be restricted, role of the data principal in public life and the nature of the disclosure among some other variables.

Do other countries recognize this right?

The Center for Internet and Society notes that the “right to be forgotten” gained prominence when the matter was referred to the Court of Justice of European Union (CJEC) in 2014 by a Spanish Court.

In this case, one Mario Costeja González disputed that the Google search results for his name continued to show results leading to an auction notice of his reposed home. González said that the fact that Google continued to show these in its search results related to him was a breach of his privacy, given that the matter was resolved, the center notes.

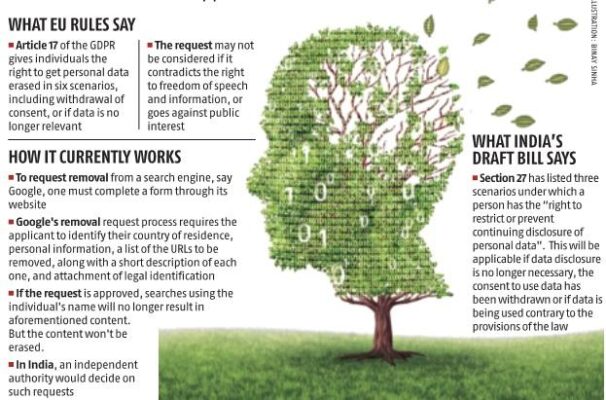

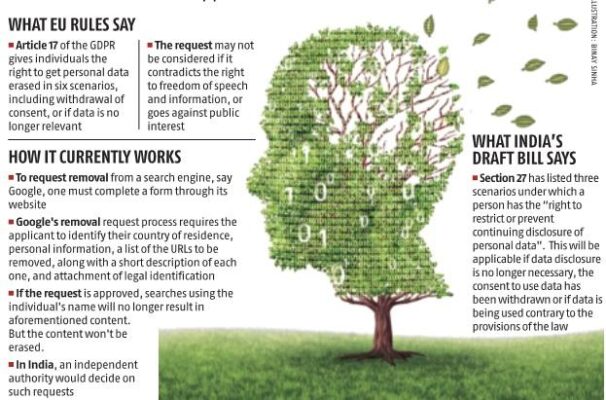

In the European Union (EU), the right to be forgotten empowers individuals to ask organisations to delete their personal data. It is provided by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a law passed by the 28-member bloc in 2018.

According to the EU GDPR’s website, the right to be forgotten appears in Recitals 65 and 66 and in Article 17 of the regulation, which states, “The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay” (if one of a number of conditions applies).

In its landmark ruling, the EU’s highest court ruled in 2019 that the ‘right to be forgotten’ under European law would not apply beyond the borders of EU member states. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in favour of the search engine giant Google, which was contesting a French regulatory authority’s order to have web addresses removed from its global database.

This ruling was considered an important victory for Google, and laid down that the online privacy law cannot be used to regulate the internet in countries such as India, which are outside the EU.

Ashutosh Kaushik who won reality shows Bigg Boss in 2008 and MTV Roadies 5.0 has approached the Delhi High Court with a plea saying that his videos, photographs and articles etc. be removed from the internet citing his “Right to be Forgotten”.

In the plea, Kaushik also maintains that the “Right to be Forgotten” goes in sync with the “Right to Privacy”, which is an integral part of Article 21 of the Constitution, which concerns the right to life.

Kaushik’s plea mentions that the posts and videos on internet related to him have caused the “petitioner psychological pain for his diminutive acts, which were erroneously committed a decade ago as the recorded videos, photos, articles of the same are available on various search engines/ online platforms”.

The plea also states that “the petitioner’s mistakes in his personal life becomes and remains in public knowledge for generations to come and therefore in the instant case, this aspect acts as an ingredient for litigation before this Hon’ble court. Consequently, the values enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and the emergent jurisprudential concept of the Right to be Forgotten becomes extremely relevant in the present case.”

Kaushik’s plea refers to an incident from 2009 when he was held by the Mumbai traffic police for drunken driving. About ten days after Kaushik’s arrest, the metropolitan magistrate court sentenced him to one-day imprisonment, imposed a fine of Rs 3,100 and also suspended his driving licence for two years. At the time, Kaushik was charged for drunken driving, for not wearing a helmet, for not carrying his driving licence and for not obeying the police officers who were on duty.

The matter was heard by the single Judge bench of Justice Rekha Palli. The next hearing on this matter will be held on 20 August 2021.

The Right to be Forgotten falls under the purview of an individual’s right to privacy, which is governed by the Personal Data Protection Bill that is yet to be passed by Parliament.

In 2017, the Right to Privacy was declared a fundamental right by the Supreme Court in its landmark verdict. The court said at the time that, “the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 and as a part of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution”.

The Personal Data Protection Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha on 11 December 2019 and it aims to set out provisions meant for the protection of the personal data of individuals.

Clause 20 under Chapter V of this draft bill titled “Rights of Data Principal” mentions the “Right to be Forgotten.” It states that the “data principal (the person to whom the data is related) shall have the right to restrict or prevent the continuing disclosure of his personal data by a data fiduciary”.

Therefore, broadly, under the Right to be forgotten, users can de-link, limit, delete or correct the disclosure of their personal information held by data fiduciaries. A data fiduciary means any person, including the State, a company, any juristic entity or any individual who alone or in conjunction with others determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data.

Even so, the sensitivity of the personal data and information cannot be determined independently by the person concerned, but will be overseen by the Data Protection Authority (DPA). This means that while the draft bill gives some provisions under which a data principal can seek that his data be removed, but his or her rights are subject to authorisation by the Adjudicating Officer who works for the DPA.

While assessing the data principal’s request, this officer will need to examine the sensitivity of the personal data, the scale of disclosure, degree of accessibility sought to be restricted, role of the data principal in public life and the nature of the disclosure among some other variables.

Do other countries recognize this right?

The Center for Internet and Society notes that the “right to be forgotten” gained prominence when the matter was referred to the Court of Justice of European Union (CJEC) in 2014 by a Spanish Court.

In this case, one Mario Costeja González disputed that the Google search results for his name continued to show results leading to an auction notice of his reposed home. González said that the fact that Google continued to show these in its search results related to him was a breach of his privacy, given that the matter was resolved, the center notes.

In the European Union (EU), the right to be forgotten empowers individuals to ask organisations to delete their personal data. It is provided by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a law passed by the 28-member bloc in 2018.

According to the EU GDPR’s website, the right to be forgotten appears in Recitals 65 and 66 and in Article 17 of the regulation, which states, “The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay” (if one of a number of conditions applies).

In its landmark ruling, the EU’s highest court ruled in 2019 that the ‘right to be forgotten’ under European law would not apply beyond the borders of EU member states. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in favour of the search engine giant Google, which was contesting a French regulatory authority’s order to have web addresses removed from its global database.

This ruling was considered an important victory for Google, and laid down that the online privacy law cannot be used to regulate the internet in countries such as India, which are outside the EU.

Next

previous

Ashutosh Kaushik who won reality shows Bigg Boss in 2008 and MTV Roadies 5.0 has approached the Delhi High Court with a plea saying that his videos, photographs and articles etc. be removed from the internet citing his “Right to be Forgotten”.

In the plea, Kaushik also maintains that the “Right to be Forgotten” goes in sync with the “Right to Privacy”, which is an integral part of Article 21 of the Constitution, which concerns the right to life.

Kaushik’s plea mentions that the posts and videos on internet related to him have caused the “petitioner psychological pain for his diminutive acts, which were erroneously committed a decade ago as the recorded videos, photos, articles of the same are available on various search engines/ online platforms”.

The plea also states that “the petitioner’s mistakes in his personal life becomes and remains in public knowledge for generations to come and therefore in the instant case, this aspect acts as an ingredient for litigation before this Hon’ble court. Consequently, the values enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and the emergent jurisprudential concept of the Right to be Forgotten becomes extremely relevant in the present case.”

Kaushik’s plea refers to an incident from 2009 when he was held by the Mumbai traffic police for drunken driving. About ten days after Kaushik’s arrest, the metropolitan magistrate court sentenced him to one-day imprisonment, imposed a fine of Rs 3,100 and also suspended his driving licence for two years. At the time, Kaushik was charged for drunken driving, for not wearing a helmet, for not carrying his driving licence and for not obeying the police officers who were on duty.

The matter was heard by the single Judge bench of Justice Rekha Palli. The next hearing on this matter will be held on 20 August 2021.

The Right to be Forgotten falls under the purview of an individual’s right to privacy, which is governed by the Personal Data Protection Bill that is yet to be passed by Parliament.

In 2017, the Right to Privacy was declared a fundamental right by the Supreme Court in its landmark verdict. The court said at the time that, “the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 and as a part of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution”.

The Personal Data Protection Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha on 11 December 2019 and it aims to set out provisions meant for the protection of the personal data of individuals.

Clause 20 under Chapter V of this draft bill titled “Rights of Data Principal” mentions the “Right to be Forgotten.” It states that the “data principal (the person to whom the data is related) shall have the right to restrict or prevent the continuing disclosure of his personal data by a data fiduciary”.

Therefore, broadly, under the Right to be forgotten, users can de-link, limit, delete or correct the disclosure of their personal information held by data fiduciaries. A data fiduciary means any person, including the State, a company, any juristic entity or any individual who alone or in conjunction with others determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data.

Even so, the sensitivity of the personal data and information cannot be determined independently by the person concerned, but will be overseen by the Data Protection Authority (DPA). This means that while the draft bill gives some provisions under which a data principal can seek that his data be removed, but his or her rights are subject to authorisation by the Adjudicating Officer who works for the DPA.

While assessing the data principal’s request, this officer will need to examine the sensitivity of the personal data, the scale of disclosure, degree of accessibility sought to be restricted, role of the data principal in public life and the nature of the disclosure among some other variables.

Do other countries recognize this right?

The Center for Internet and Society notes that the “right to be forgotten” gained prominence when the matter was referred to the Court of Justice of European Union (CJEC) in 2014 by a Spanish Court.

In this case, one Mario Costeja González disputed that the Google search results for his name continued to show results leading to an auction notice of his reposed home. González said that the fact that Google continued to show these in its search results related to him was a breach of his privacy, given that the matter was resolved, the center notes.

In the European Union (EU), the right to be forgotten empowers individuals to ask organisations to delete their personal data. It is provided by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a law passed by the 28-member bloc in 2018.

According to the EU GDPR’s website, the right to be forgotten appears in Recitals 65 and 66 and in Article 17 of the regulation, which states, “The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay” (if one of a number of conditions applies).

In its landmark ruling, the EU’s highest court ruled in 2019 that the ‘right to be forgotten’ under European law would not apply beyond the borders of EU member states. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in favour of the search engine giant Google, which was contesting a French regulatory authority’s order to have web addresses removed from its global database.

This ruling was considered an important victory for Google, and laid down that the online privacy law cannot be used to regulate the internet in countries such as India, which are outside the EU.

Ashutosh Kaushik who won reality shows Bigg Boss in 2008 and MTV Roadies 5.0 has approached the Delhi High Court with a plea saying that his videos, photographs and articles etc. be removed from the internet citing his “Right to be Forgotten”.

In the plea, Kaushik also maintains that the “Right to be Forgotten” goes in sync with the “Right to Privacy”, which is an integral part of Article 21 of the Constitution, which concerns the right to life.

Kaushik’s plea mentions that the posts and videos on internet related to him have caused the “petitioner psychological pain for his diminutive acts, which were erroneously committed a decade ago as the recorded videos, photos, articles of the same are available on various search engines/ online platforms”.

The plea also states that “the petitioner’s mistakes in his personal life becomes and remains in public knowledge for generations to come and therefore in the instant case, this aspect acts as an ingredient for litigation before this Hon’ble court. Consequently, the values enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and the emergent jurisprudential concept of the Right to be Forgotten becomes extremely relevant in the present case.”

Kaushik’s plea refers to an incident from 2009 when he was held by the Mumbai traffic police for drunken driving. About ten days after Kaushik’s arrest, the metropolitan magistrate court sentenced him to one-day imprisonment, imposed a fine of Rs 3,100 and also suspended his driving licence for two years. At the time, Kaushik was charged for drunken driving, for not wearing a helmet, for not carrying his driving licence and for not obeying the police officers who were on duty.

The matter was heard by the single Judge bench of Justice Rekha Palli. The next hearing on this matter will be held on 20 August 2021.

The Right to be Forgotten falls under the purview of an individual’s right to privacy, which is governed by the Personal Data Protection Bill that is yet to be passed by Parliament.

In 2017, the Right to Privacy was declared a fundamental right by the Supreme Court in its landmark verdict. The court said at the time that, “the right to privacy is protected as an intrinsic part of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 and as a part of the freedoms guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution”.

The Personal Data Protection Bill was introduced in Lok Sabha on 11 December 2019 and it aims to set out provisions meant for the protection of the personal data of individuals.

Clause 20 under Chapter V of this draft bill titled “Rights of Data Principal” mentions the “Right to be Forgotten.” It states that the “data principal (the person to whom the data is related) shall have the right to restrict or prevent the continuing disclosure of his personal data by a data fiduciary”.

Therefore, broadly, under the Right to be forgotten, users can de-link, limit, delete or correct the disclosure of their personal information held by data fiduciaries. A data fiduciary means any person, including the State, a company, any juristic entity or any individual who alone or in conjunction with others determines the purpose and means of processing of personal data.

Even so, the sensitivity of the personal data and information cannot be determined independently by the person concerned, but will be overseen by the Data Protection Authority (DPA). This means that while the draft bill gives some provisions under which a data principal can seek that his data be removed, but his or her rights are subject to authorisation by the Adjudicating Officer who works for the DPA.

While assessing the data principal’s request, this officer will need to examine the sensitivity of the personal data, the scale of disclosure, degree of accessibility sought to be restricted, role of the data principal in public life and the nature of the disclosure among some other variables.

Do other countries recognize this right?

The Center for Internet and Society notes that the “right to be forgotten” gained prominence when the matter was referred to the Court of Justice of European Union (CJEC) in 2014 by a Spanish Court.

In this case, one Mario Costeja González disputed that the Google search results for his name continued to show results leading to an auction notice of his reposed home. González said that the fact that Google continued to show these in its search results related to him was a breach of his privacy, given that the matter was resolved, the center notes.

In the European Union (EU), the right to be forgotten empowers individuals to ask organisations to delete their personal data. It is provided by the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a law passed by the 28-member bloc in 2018.

According to the EU GDPR’s website, the right to be forgotten appears in Recitals 65 and 66 and in Article 17 of the regulation, which states, “The data subject shall have the right to obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay and the controller shall have the obligation to erase personal data without undue delay” (if one of a number of conditions applies).

In its landmark ruling, the EU’s highest court ruled in 2019 that the ‘right to be forgotten’ under European law would not apply beyond the borders of EU member states. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled in favour of the search engine giant Google, which was contesting a French regulatory authority’s order to have web addresses removed from its global database.

This ruling was considered an important victory for Google, and laid down that the online privacy law cannot be used to regulate the internet in countries such as India, which are outside the EU.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies