- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

Social security in platform workers in the Gig Economy

Recent Code on Social Security Bill, 2020, for the first time in Indian law acknowledges platform workers and gig workers as new occupational categories. The bill attempts to define ‘platform work’ outside of the traditional employment category.

The bill defines Platform work as a work arrangement outside of a traditional employer-employee relationship in which organisations or individuals use an online platform to access other organisations or individuals.

People working on digital platforms like Uber, Ola, Zomato, Swiggy and UrbanClap can be termed as Platforms workers.

The bill aims to bring digital labour platforms within the purview of new or existing employment and labour regulations in India. However, there is a lot to be done in order to ensure all relevant labour benefits for those working in the ‘gig economy’.

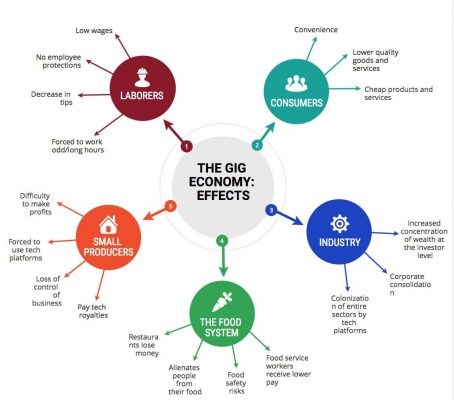

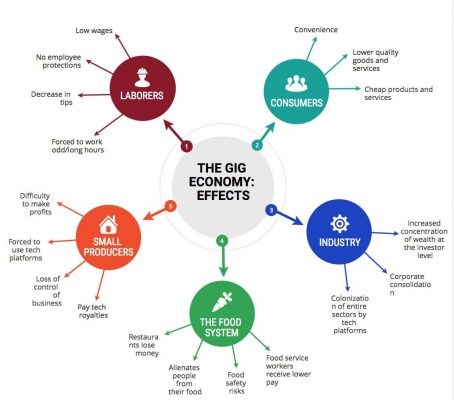

Significance of Gig Economy

Need for Protection of Platform Workers

Need for Protection of Platform Workers

- Providing Employment In Urban Areas: At the moment, the manufacturing sector in India is unable to provide employment opportunities to the youth. There is thus a mismatch between education and jobs skills in the market.

- Governments have also been unable to create viable public work schemes in urban areas for those continuously migrating into cities and towns.

- Gig Economy, however, has been able to provide employment opportunities in urban areas.

- Due to this, the Governments now actively acknowledge that platforms provide work to the growing demographic of youth in the country.

- Augmenting Social Services: Central and many state governments have signed MOUs with several gig platforms to augment social services.

- For example, Uber partnered with Ayushman Bharat to facilitate free healthcare for drivers and delivery partners.

- UrbanClap partnered with the National Urban Livelihoods Mission to generate jobs with minimum assured monthly wages for the urban poor.

- In cases of informal jobs where it was difficult to identify workers for whom protection was to be given, platforms became vehicles to serve this purpose.

- Enabling Jobs For All Scenario: Gig economy based companies helps to create work, entrepreneurial opportunities and skill development.

- With the right ecosystem of public policy, platform work, and the government together can suggest an urban ‘Jobs for All’, a financialised employment guarantee scheme.

Need for Protection of Platform Workers

Need for Protection of Platform Workers

- Benefits But Not Rights: Platform delivery people can claim benefits, but not labour rights.

- Present legal framework does not allow them to go to court to demand better and stable pay, or regulate the algorithms that assign the tasks.

- This also means that the government or courts cannot pull up platform companies for their choice of pay, or how long they ask people to work.

- Arbitrary Action: During the last six months, many platform workers have unionised under the All India Gig Workers Union and have protested for continuous dip in pay.

- For example, Swiggy workers have been essential during the pandemic. Even after that pay of Swiggy workers was reduced from ₹35 to ₹10 per delivery order.

- International Experience: Many international agencies in the EU are demanding a move towards granting employee status to platform workers, thus guaranteeing minimum wage and welfare benefits.

- Vulnerability of Debt Trap: In order to enter the platform economy, workers rely on intensive loan schemes, often facilitated by platform aggregator companies.

- This results in dependence on platform companies, driven by financial obligations, thus rendering them into the short- to middle-term debt trap.

- No Guarantee of Benefits: In the Code on Social Security bill , 2020, platform workers are now eligible for benefits like maternity benefits, life and disability cover, old age protection, provident fund, employment injury benefits, etc.

- However, eligibility does not mean that the benefits are guaranteed.

- None of the provisions secure benefits, which means that from time to time, the Central government can formulate welfare schemes that cover these aspects of personal and work security, but they are not guaranteed.

- No Fixed Responsibility: The Code states the provision of basic welfare measures as a joint responsibility of the Central government, platform aggregators, and workers.

- However, it does not state which stakeholder is responsible for delivering what quantum of welfare.

- Need For Clarity: A categorical clarification could ensure that social security measures are provided to workers without compromising the touted qualities of platform work.

- Joint Accountability: There is a need for a socio-legal acknowledgement of the heterogeneity of work in the gig economy, and the ascription of joint accountability to the State and platform companies for the delivery of social services.

- Concerted Efforts: To mitigate operational breakdowns in providing welfare services, a tripartite effort by the State, companies, and workers to identify where workers fall on the spectrum of flexibility and dependence on platform companies is critical.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies