- Home

- Prelims

- Mains

- Current Affairs

- Study Materials

- Test Series

SHANTI Bill: Peace through Nuclear Energy ?

- The Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Bill, 2025, is a landmark piece of legislation passed by the Indian Parliament in December 2025. It overhauls India''s nuclear governance by replacing the 63-year-old Atomic Energy Act, 1962, and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010.

- President Droupadi Murmu granted assent to the Bill on December 20, 2025, marking a major overhaul of India’s nuclear governance framework.

Nuclear Energy and the SHANTI Bill

What is the SHANTI Bill?

- The SHANTI Bill, 2025 replaces the Atomic Energy Act, 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act, 2010.

- It provides a new legal framework to expand nuclear power, permit private participation, and restructure liability and regulation in the nuclear sector.

Core Objectives

- Energy Transition: Aims to scale India’s nuclear capacity from approximately 8 GW in 2025 to 100 GW by 2047 to meet Net Zero goals.

- Private Participation: Ends the state monopoly (previously held by NPCIL) by allowing Indian private companies and joint ventures to build, own, operate, and decommission nuclear plants.

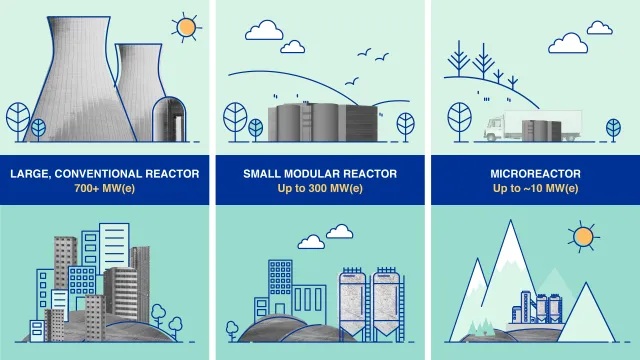

- Technological Advancement: Specifically incentivizes the development and deployment of Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) for industrial and captive power use.

Key features of the Bill

- Opening nuclear sector to non-government entities: The Bill allows licences for building, owning and operating nuclear plants to private companies, joint ventures and other permitted persons, under government licensing and regulatory oversight.

- Tiered liability framework: It introduces graded operator liability caps ranging from ₹100 crore to ₹3,000 crore based on reactor capacity, with excess liability borne by the central government.

- Removal of supplier liability for defects: The operator’s “right of recourse” against suppliers for defective equipment or materials is removed, retaining recourse only for contractual or deliberate acts, aligning India with global standards to attract foreign vendors.

- Statutory status to AERB: The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) is granted statutory recognition, tasked with ensuring nuclear and radiation safety.

- Expanded territorial coverage of claims: Compensation claims may now extend to nuclear damage in foreign territories, subject to specified conditions.

- New appellate mechanism: The Bill establishes an Atomic Energy Redressal Advisory Council, with further appeals lying before the Appellate Tribunal for Electricity.

|

Why Right of Recourse Removed?

The erstwhile CNLD allowed operators to claim recourse from a supplier of equipment under three instances: if (a) the supplier and an operator have an explicit agreement (b) the nuclear incident has proved to be due to the suppliers or their equipment’s fault (c) the nuclear incident has resulted from deliberate intent to cause nuclear damage. In SHANTI, clause (b) has been done away with. Despite the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal of 2008 that allowed India access to uranium and international nuclear technology (restricted, because of its nuclear tests of 1974 and 1998), American, and French makers of reactors were hesitant because as ‘suppliers’ they could in theory be held liable for billions of dollars. With the elimination of clause (b) and even the deletion of the word ‘supplier,’ this ‘problem’ vanishes.

|

Need for the SHANTI Bill

- Rising energy demand and decarbonisation goals: India’s growing economy and digitalisation require massive energy expansion, while net-zero commitments demand low-carbon baseload sources like nuclear.

- Limitations of renewables alone: Solar and wind are intermittent, land-intensive and storage-dependent; nuclear provides reliable baseload power for a decarbonised grid.

- Public sector capacity constraints: NPCIL and DAE face financial and execution limits in scaling up nuclear capacity to 100 GW without private capital and expertise.

- Global best practices and investment flows: Opening the sector aligns India with global nuclear markets and enables access to technology, finance and supply chains.

Issues associated with the SHANTI Bill

- Dilution of liability and public safety concerns: Low liability caps and removal of supplier liability risk socialising catastrophic costs, contrary to the polluter pays principle.

- Lessons from Bhopal and Fukushima ignored: Past industrial disasters underline the need for strong accountability, which critics argue the Bill weakens.

- Regulatory independence questioned: Despite statutory status, AERB remains executive-controlled, raising concerns of regulatory capture.

- Radioactive waste and decommissioning gaps: The Bill lacks a clear funding and responsibility framework for long-term waste management and decommissioning.

- Labour and environmental justice risks: Private participation may increase reliance on contract labour, heightening occupational and environmental risks.

- Energy sovereignty concerns: Higher foreign participation could deepen technology dependence, weakening India’s indigenous nuclear trajectory.

|

Issue with SMR

|

Way ahead

- Strengthen liability and accountability mechanisms: Revisit liability caps, restore meaningful supplier accountability, and introduce explicit criminal negligence provisions.

- Ensure truly independent regulation: Reform appointment processes and empower AERB with autonomy, transparency and parliamentary oversight.

- Create a nuclear waste and decommissioning fund: Mandate fully funded, ring-fenced mechanisms to manage intergenerational radioactive waste burdens.

- Balance nuclear expansion with renewables: Adopt a diversified energy strategy, prioritising grid modernisation, storage and energy efficiency alongside nuclear.

- Enhance public consultation and trust: Institutionalise community participation, environmental safeguards and transparency in nuclear siting and operations.

Conclusion

- The SHANTI Bill, 2025 represents a transformative shift in India’s nuclear energy governance, driven by decarbonisation and development goals. While it can unlock investment and accelerate capacity expansion, weakened liability, regulatory risks and safety concerns remain significant. A balanced approach —combining nuclear growth with strong accountability, public trust and renewable integration— is essential for sustainable energy security.

Latest News

Latest News

General Studies

General Studies