India and Australia on 4 July 2022 decided to strengthen their partnership in the field of projects and supply chains for critical minerals.

As part of his six-day tour of Australia, Union Coal and Mines Minister Pralhad Joshi met his counterpart, Resources and Northern Australia Minister Madeleine King, after which Australia confirmed that it would “commit A$5.8 million to the three-year India-Australia Critical Minerals Investment Partnership”.

“Australia has the resources to help India fulfil its ambitions to lower emissions and meet growing demand for critical minerals to help India’s space and defence industries, and the manufacture of solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles….Australia welcomes India’s strong interest and support for a bilateral partnership which will help advance critical minerals projects in Australia while diversifying global supply chains,” King said.

What are critical minerals?

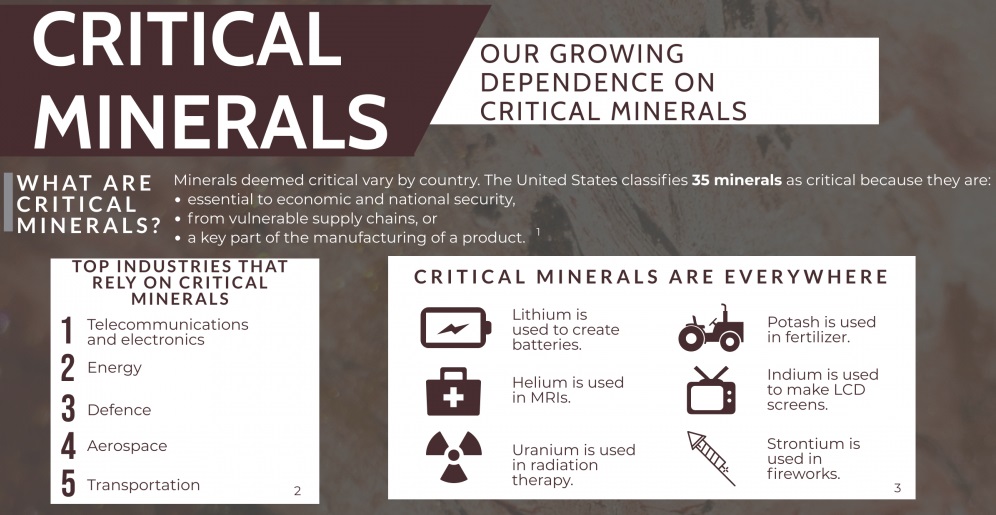

Critical minerals are elements that are the building blocks of essential modern-day technologies, and are at risk of supply chain disruptions. These minerals are now used everywhere from making mobile phones, computers to batteries, electric vehicles and green technologies like solar panels and wind turbines. Based on their individual needs and strategic considerations, different countries create their own lists.

However, such lists mostly include graphite, lithium and cobalt, which are used for making EV batteries; rare earths that are used for making magnets and silicon which is a key mineral for making computer chips and solar panels. Aerospace, communications and defence industries also rely on several such minerals as they are used in manufacturing fighter jets, drones, radio sets and other critical equipment.

Why is this resource critical?

As countries around the world scale up their transition towards clean energy and digital economy, these critical resources are key to the ecosystem that fuels this change. Any supply shock can severely imperil the economy and strategic autonomy of a country over-dependent on others to procure critical minerals.

But these supply risks exist due to rare availability, growing demand and complex processing value chain. Many times the complex supply chain can be disrupted by hostile regimes, or due to politically unstable regions.

As a US government statement in February noted: “As the world transitions to a clean energy economy, global demand for these critical minerals is set to skyrocket by 400-600 per cent over the next several decades, and, for minerals such as lithium and graphite used in electric vehicle (EV) batteries, demand will increase by even more — as much as 4,000 per cent.”

They are critical as the world is fast shifting from a fossil fuel-intensive to a mineral-intensive energy system.

What is the China ‘threat’?

According to the 2019 USGS Mineral Commodity Summaries report, China is the world’s largest producer of 16 critical minerals.

China, according to a report on the role of critical minerals by the International Energy Agency, is “responsible for some 70% and 60% of global production of cobalt and rare earth elements, respectively, in 2019. The level of concentration is even higher for processing operations, where China has a strong presence across the board. China’s share of refining is around 35% for nickel, 50-70% for lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90% for rare earth elements.”

It also controls cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, from where 70% of this mineral is sourced.

In 2010, China suspended rare earth exports to Japan for two months over a territorial dispute. The decision, according to the Brookings Institution, made the market prices of RREs jump anywhere between 60% to 350%. The prices returned to normal only after a year of China resuming shipments.

What are countries around the world doing about it?

In 2021, the US ordered a review of vulnerabilities in its critical minerals supply chains and found that an over-reliance on “foreign sources and adversarial nations for critical minerals and materials posed national and economic security threats”. Post the supply chain assessment, it has shifted its focus on expanding domestic mining, production, processing, and recycling of critical minerals and materials.

India has set up KABIL or the Khanij Bidesh India Limited, a joint venture of three public sector companies, to “ensure a consistent supply of critical and strategic minerals to the Indian domestic market”. Announcing the formation of KABIL in 2019, Coal and Minister Pralhad Joshi had said: “While KABIL would ensure mineral security of the nation, it would also help in realizing the overall objective of import substitution.”

Australia’s Critical Minerals Facilitation Office (CMFO) and KABIL had recently signed an MoU aimed at ensuring reliable supply of critical minerals to India.

The UK on 4 July 2022 unveiled its new Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre to study the future demand for and supply of these minerals. It also said that the country’s critical mineral strategy will be unveiled later this year.

In June last year, the US, Canada and Australia had launched an interactive map of critical mineral deposits with an aim to help governments to identify options to diversify their critical minerals sources.

Latest News

Latest News EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

EDITORIALS & ARTICLES

General Studies

General Studies